In the Footsteps of Pablo Picasso

Discover how Picasso was both revered and reviled in France, while this year marks the 50th anniversary of the Francophile painter’s death

One of Pablo Picasso’s trademark passions in life – alongside art and women – was his adopted home country of France. By the time the Malaga-born artist (whose first ever word was “piz”, an abbreviation of lapiz, the Spanish word for pencil) hit his teens, his passion for Paris had compelled him to leave his relatively comfortable middle-class life in Spain and plunge himself into abject poverty. From his permanent relocation to France aged 19 until his death in Mougins at the age of 91, he earned himself various labels – from “billionaire communist” to “honorary citizen” – so it’s safe to say his profile polarised public opinion.

Read More: Picasso: 50th Anniversary

Poverty in Paris

Though some later regarded him as a wealthy political oppressor, his early beginnings were far from that; in fact, Picasso was painfully poor and his Paris apartment was so cold he would burn much of his own work shortly after creating it just to keep warm.

Later, he shared a studio with his volatile pal Carles Casagemas, who shot himself after being spurned by a love interest. The scene of his suicide was

the Hippodrome Café in Paris, at 128 Boulevard de Clichy (today the Bel-Ami restaurant and bar), the street where Picasso had his studio, although he was away in Madrid at the time. Picasso honoured his late friend with a seemingly Van Gogh-inspired expressionist painting, The Death of Casagemas.

Such drama might not have seemed the best environment to fuel his creativity, but Picasso thrived in Paris and by 1904 he had left Spain for ever. It was at this point that he transitioned from his Blue Period, which channelled the angst of the abject poverty and frustration he’d seen around him, to his Rose Period, with art that was more joyful and optimistic. Having now opened multiple studios and gained a foothold in his host city, he was no longer feeling the blues.

He was heavily inspired during this period by Montmartre, filling his paintings with acrobats, harlequins and showgirls. His studio was just doors away from the Moulin Rouge, where bellydancers writhed inside a giant wooden elephant. Life saw Picasso toiling away at his studio by day and enjoying lavish theatrical performances of dance, drama, cabaret and circus by night.

The saucier side of life was immortalised in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, his first major foray into Cubism. It was inspired by a visit to the Palais du Trocadéro’s ethnographic museum, where he was introduced to African art and masks. Picasso later recalled that moment, wandering, rapt, among the artefacts, as the time when the Demoiselles came alive, in his “first exorcising painting” ever.

Read More: Picasso’s Women

Picasso and friends at the Café de la Rotonde

Café Culture

He rushed home to create his masterpiece at Le Bateau Lavoir, at 13 Rue Ravignan, where his latest studio was located. The venue, whose name translates to ‘laundry boat’ in a nod to the public washing boats that were once moored around the Seine, was popular with artists seeking rock-bottom rental fees. The building – recreated after a fire in the 1970s – has since been privatised by modern-day resident artists, although a plaque commemorating its history still remains there.

Picasso’s other favourite haunts included the Café de la Rotonde (which is still open today), where the owner accepted artwork in lieu of payment for coffee and cake. Here Picasso indulged in snacks with famous pals such as Cocteau and Modigliani.

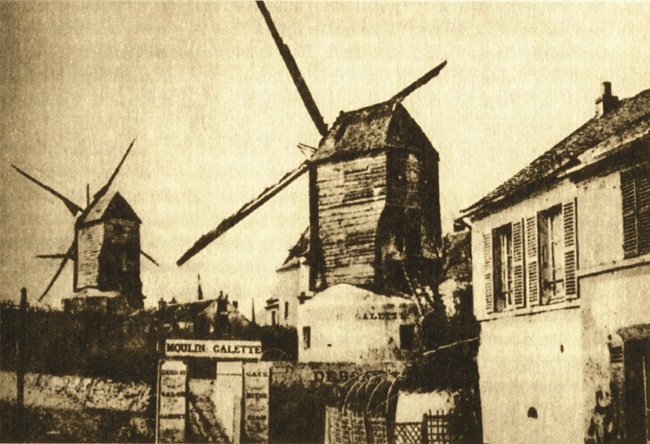

Back in Montmartre, those following in Picasso’s footsteps can also visit the Moulin de la Galette, a restaurant with a huge windmill atop its roof in a nod to the district’s agricultural roots. Sadly Cirque Medrano, the circus venue where he gained inspiration for some of his most acclaimed early work, no longer exists. Once a visual feast of violin-wielding clowns and lithe acrobats juggling bottles beneath their feet with astonishing speed and dexterity, it is today the venue of a rather less exciting Carrefour supermarket. The show, once adored by Toulouse-Lautrec and Renoir too, now tours the country.

Another of Picasso’s Parisian haunts was the Louvre – and, in 1911, he came perilously close to being convicted of the theft of its most famous mascot – the Mona Lisa. Today, the masterpiece is protected by state-of-the-art security in its own bulletproof case – but back in Picasso’s day, it wasn’t even bolted to the wall, fastened instead from a few shaky hooks. Once, in a bid to prove how dismal the security was, a reporter even slipped into a sarcophagus for the night – an intrusion which went entirely undetected. With a skeleton crew guarding some 250,000 exhibits, it was only a matter of time before France’s national treasure was swiped away.

The Moulin de la Galette in Picasso’s day

Day in Court

When the worst happened, Picasso instantly became a suspect. He’d been close to poet Guillaume Apollinaire, whose secretary had stolen smaller items from the Louvre previously and sold the spoils – two Iberian sculptures – to him. Picasso and his pal panicked and plotted to throw them in the Seine at the dead of night to exonerate themselves, before having a change of heart and returning them. Now, as he stood accused of stealing the Mona Lisa, Picasso wept bitterly before the judge and denied ever having seen Apollinaire before. The case was eventually thrown out, and an Italian Louvre employee who’d wanted to return Da Vinci’s work to its country of origin was found guilty instead.

Surprisingly, Picasso and Apollinaire’s friendship endured after the trial and the latter was even one of the best men (along with Jean Cocteau) at Picasso’s 1918 wedding to ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova, held at the Russian Orthodox Cathédrale Saint-Alexandre-Nevsky, in the 8th arrondissement.

Picasso continued to experiment with Cubism and Surrealism, and in 1937 he set up a new attic studio at 7 Rue Grands-Augustins, which is now a protected landmark. Why was this studio significant? It was a symbol of the Resistance movement and Picasso’s desire to triumph against censorship amid one of the most catastrophic wars the world had ever seen. Within weeks of moving in, the Spanish town of Guernica was bombed by Nazi war planes, causing thousands of casualties. In response, Picasso indulged in some art therapy – and soon, one of his most famous paintings of all time was born. Named after the town itself, it depicted the chaos and carnage of war, and among the screaming and terrified people is the harrowing image of a dead baby.

Before long, France, too, was in the Nazis’ clutches, and no one was safe. Alongside human casualties, creativity was also under threat. Picasso was branded the “most degenerate artist in the world”, while some around him had their homes raided and artworks confiscated. Picasso delivered a scathing retort when visiting soldiers asked him of Guernica, “Did you do that?”. “No,” Picasso shot back. “You did.”

He refused to leave his beloved Paris – even when Nazi occupation turned it upside down. His books were banned, and exhibitions prohibited, but he’d come to Paris to be part of a movement of freedom-loving creatives, so it was a matter of principle for him to refuse to abandon those values – even when many fellow artists gave up and fled. Works such as Weeping Woman kept his creative spirit engaged during the war. He also became ever more innovative, getting bronze smuggled in by Resistance forces so that, after the Nazis outlawed bronze casting, he could carry on creating his sculptures in secret.

Picasso continued to suffer in silence until Paris was liberated, but by 1946, he’d fallen in love with the Riviera town of Antibes. But before leaving the capital to follow in his footsteps south, a must on any art lover’s itinerary is a visit to the Musée Picasso, in Rue de Thorigny in the Marais. Boasting 5,000 of his artworks, it bills itself as “the world’s richest public collection” ever created on the artist. Setting aside a day to explore this veritable goldmine is essential.

Read More: Following Picasso on the French Riviera

Château de Vauvenargues, Picasso’s former home © Mathieu Brossais, Wikimedia

Life in the south

The Musée Picasso in Antibes is a far more modest collection of his work, but it comes with the added bonus of its location in the Château Grimaldi – the artist’s former home. He spent a mere matter of months there, but donated most of the work produced during that time to the town. It was in Antibes where he was awarded the official title of ‘Honorary Citizen’ – and reportedly received a much warmer welcome than in politically fraught post-war Paris. Picasso then flitted through a number of Riviera towns, settling in Vallauris, near Nice, for several years. There’s a museum dedicated to him there, named the Musée national Pablo Picasso – La Guerre et la Paix, and true to its name, there’s an awe-inspiring installation featuring images of both war and peace, side by side.

Later, he settled with second wife Jacqueline Roque, who was 46 years his junior, in Vauvenargues, a stone’s throw from Aix-en-Provence. The pair found a huge château with hilltop views of Mont Sainte-Victoire – the same picturesque landscapes that were immortalised by Paul Cézanne, whom Picasso openly revered as “my one and only master”.

Finally, for the last 12 years of his life, Picasso chose the hilltop village of Mougins to call home. Though it was way off the tourist radar at the time, it’s now an obligatory hideaway for celebrities seeking seclusion while attending the Cannes Film Festival in the city below.

For anyone seeking their own grand retreat in the sumptuous style to which Picasso had become accustomed, Le Manoir de l’Étang in Mougins ticks all the boxes. A hilltop manor house with its own lake set in four hectares of land and boasting incredible views, it’s the perfect place to base yourself for a spot of sightseeing. Mougins was Picasso’s final port of call before he sadly succumbed to a cardiac arrest aged 91.

Due to his communist leanings and locals’ perceptions of his excessive wealth, the mayor of the village reportedly refused to bury him there, so he was laid to rest in the gardens at the Château de Vauvenargues instead.

Picasso was a divisive character, yet he was intensely loved by his friends and followers. In fact, his wife Jacqueline was so devoted she chose suicide rather than continuing to live without him.

With the 50th anniversary of his death on April 8 this year, there’s never been a better time to plan your own Picasso pilgrimage, from his beginnings in Paris to his final resting place in the south

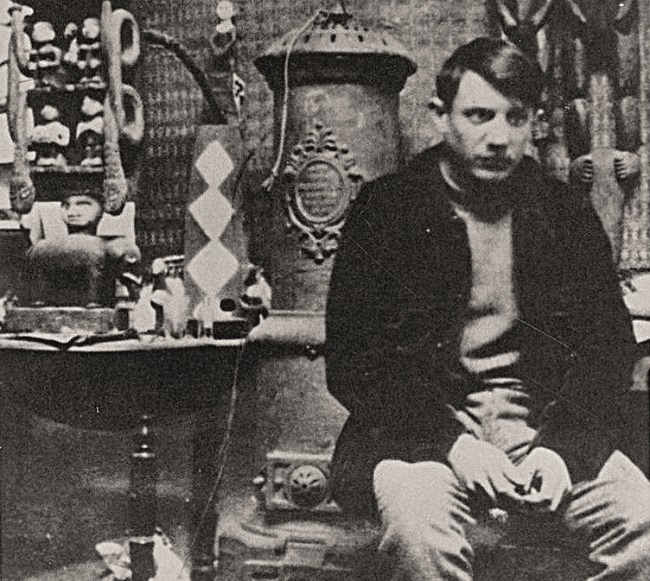

Lead photo credit : Pablo Picasso in his Montmartre studio

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in artist, history, History of Art, Pablo Picasso, painter

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *