Creative Spark: Misia Sert, Pianist and Patron of the Arts

She was an accomplished pianist, but Misia Sert was also an artists’ muse, and a patron of the arts. Hazel Smith recounts her colourful career – and remarkable life…

Artists and writers, musicians and dancers were all beguiled by Misia Sert. Considered an unparalleled beauty of her age, this muse and patron of the Paris avant-garde was immortalised by the painters Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, and at least seven times by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. She was a fiery red-head of the fin de siècle who played the piano exceptionally well and fanned the flame of artistic genius.

Misia Godebska was born in St Petersburg on March 30, 1872. She never knew her mother, who died in childbirth. Her father Cyprien Godebski, a sculptor busy with the reconstruction of the Tsar’s palace and a new marriage, sent his tiny daughter away. Misia was enveloped in love at her grandmother’s luxurious Belgian villa where, at the side of Franz Liszt, her talent as a pianist was first discovered. It is said she could confidently pick out notes on the piano before she could read. At the age of eight she was reunited with her emotionally cold father and his wife in Paris. After this, when she wasn’t preoccupied with running away from home, Misia was shunted off to a succession of convent schools.

Misia at the piano by Toulouse-Lautrec, 1897

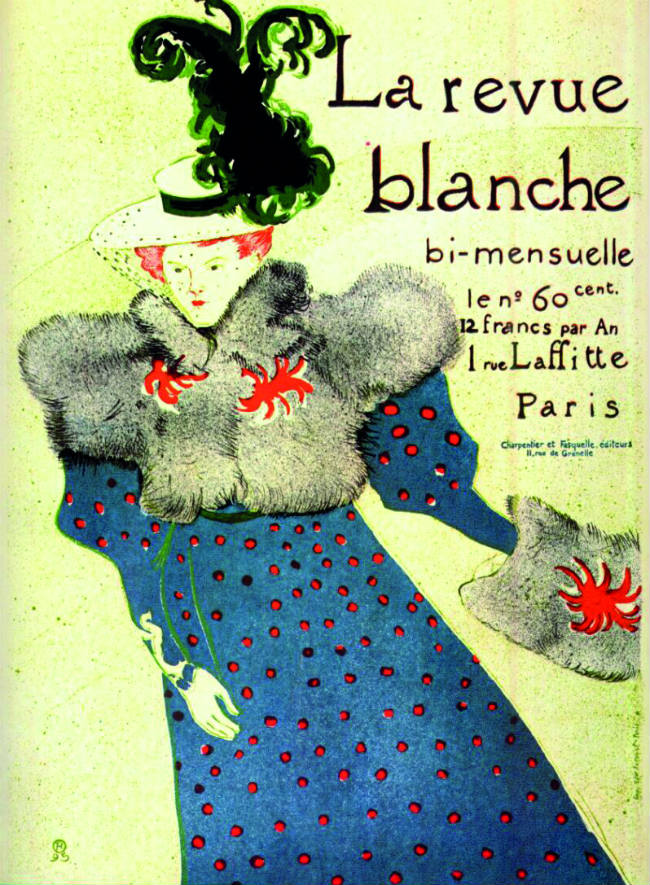

In 1893, she married Thadée Natanson, an art connoisseur and businessman who founded the arts and literary magazine La Revue Blanche, an influential journal focusing on the avant-garde circle of Paris artists. Juggling art as both a game and a religion, La Revue Blanche ran from 1889 to 1903 and was a publication like no other. You had to know the editor’s wife before being featured in its pages and Misia, who was recognised for her innovative taste, only wanted to chum about with those who were truly gifted. She wielded a great deal of influence for one who, rumour had it, had never read a whole book. Her instincts were sound, however. She and Thadée embraced the experimental in art with insights it would take the rest of society years to achieve.

Misia with Renoir after the funeral of Stéphane Mallarmé

A tart yet tender princess, Misia’s speech was peppered with profanities whenever she was defending the artistic pioneers she loved. Contributors to La Revue Blanche included Alfred Jarry, Marcel Proust, Stéphane Mallarmé, André Gide and Guillaume Apollinaire. Illustrations by Les Nabis painters Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard graced its pages, with Toulouse-Lautrec’s portrait of Misia skating across the cover of issue 60.

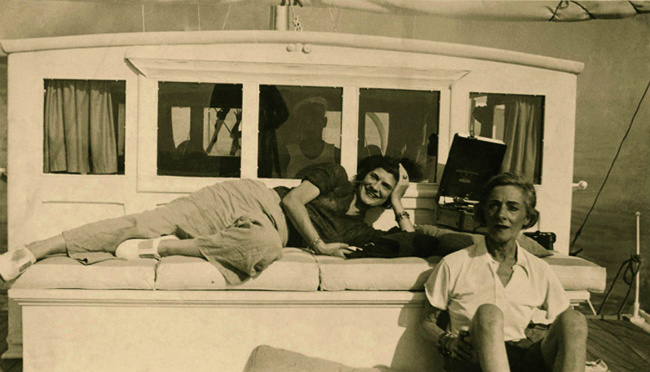

Misia Natanson in Cannes, 1901, photographed by Édouard Vuillard

LA BELLE ÉPOQUE

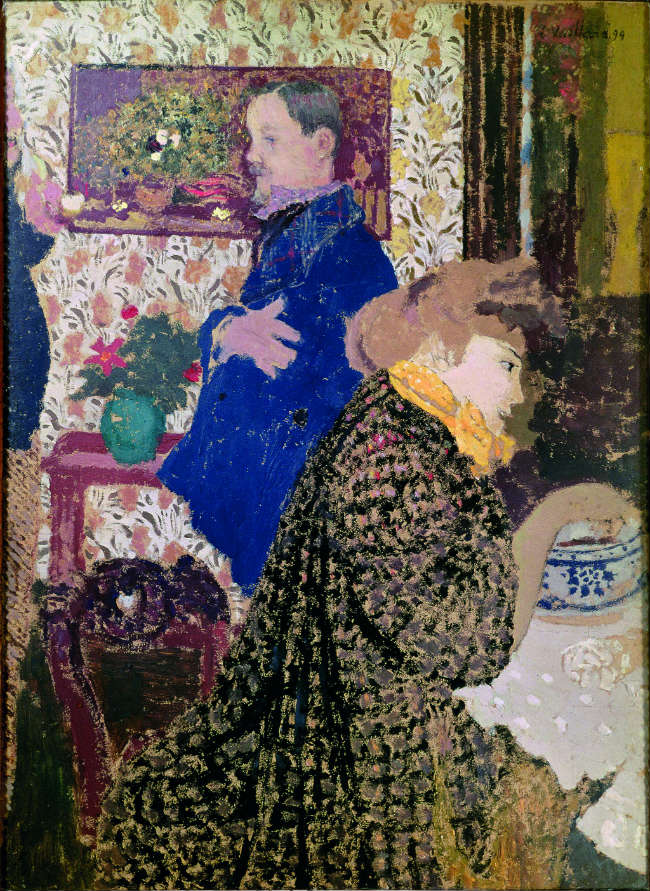

The creative minds of the Belle Époque were at her fingertips. Claude Debussy aired his compositions on Misia’s piano at 9 rue Saint-Florentin. Mallarmé, an old friend, presented her with a poem handwritten on a Japanese fan. Colette and her exploitative husband Willy were frequent callers to her salon. Situated near Place de la Concorde, the Natansons’ apartment was a riot of colour and pattern. Vuillard couldn’t wait to paint Misia in her hotchpotch surroundings. He was spellbound by her, and his adoration for his muse infused all his work during the most lucrative part of his career.

Portrait of Misia by Pierre Bonnard, 1895. Musée Thyssen-Bornemisza

Bonnard, Toulouse-Lautrec and the established Renoir joined Vuillard on the list of artists charmed by Misia. Although she was unconventionally pretty, to the painters Misia was miraculous with her amazing legs and wonderful bosom. A mistress of feminine guile, she carried herself with style, knowing just how to lean on a parasol, how to flutter a fan and how to show off her curvaceous arms and breasts to best advantage. Renoir loved Misia’s joie de vivre. She looked like one of his extended ‘family’ of models and he constantly pleaded with her to be allowed to paint her with her breast bared, though that wish was never granted. Eventually, the Natansons’ personal art collection – which the perennially cash-strapped Thadée would later have to sell – included Renoir paintings, plus 19 Bonnards and 27 Vuillards, as well as many works by Cézanne, Delacroix and Seurat.

La comtesse Etienne de Beaumont, Coco Chanel, Misia, and the comtesse Moretti

Misia and Thadée bought a series of country homes, ostensibly as summer annexes for La Revue Blanche offices. The couple scoured the countryside in one of the first motorcars in France and found the ivy-covered La Grangette in the village of Valvins. When they decided they needed even more room for their never-ending house parties, they purchased Le Relais, a manor on the banks of the river Yonne. Misia’s covey of painters followed her from house to house, while Vuillard and Bonnard, to all intents and purposes, moved in with the Natansons.

With his new folding Kodak, Vuillard would wander the grounds adding to a collection of pictures that now comprises most of the known photographs of Misia. Toulouse-Lautrec tagged along too, the little libertine tempting weekend friends with gastronomic delights prepared on the Natansons’ stove. The days were a blur of music, plays, picnics and games – but when you throw heavenly parties, you pay outrageous bills. In the course of their young lives together, Thadée made – and lost – several fortunes.

Misia’s image on the cover of “La Revue Blanche”

BANKRUPTCY AND DIVORCE

By 1900 Thadée was facing bankruptcy. He had tired of La Revue Blanche and entered into less lucrative ventures. Misia, meanwhile, had caught the eye of the vulgar newspaper baron Alfred Edwards, editor of Le Matin. Thadée wasted no time in pandering his 28-year-old wife out like a pimp, urging Misia to use her considerable charms to secure Edwards’ financial backing. But Thadée’s plan ultimately back red. Edwards wanted her as his wife, despite the fact that he too was already married.

Misia Sert

Bungling Thadée resigned himself to the new situation and cabled Misia to “arrange everything”. In her own words, Misia had exchanged “a charming, subtle and erudite playmate” for a boor who turned her into “the most spoiled little girl in the world”. She moved in with Edwards and they married in 1905, setting up home at an apartment at 244 rue de Rivoli, overlooking the Tuileries Garden.

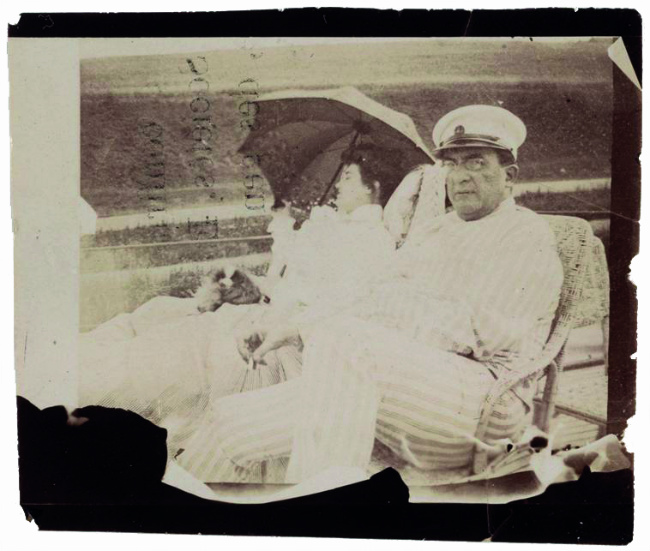

Misia and her second husband. Credit: Orsay Museum

Misia found still more friends on the never-ending carousel of Parisian musicians and artists. As an inspiration to Proust (Misia became Princess Yourbeletieff in Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu), she was “the youthful sponsor of all these new great men”. Maurice Ravel’s Le Cygne was dedicated to her. When Misia’s “petit Ravel” failed for the third time to win the prestigious Prix de Rome, she used her new husband’s clout to have the director of the Conservatoire fired. After the scandal, Ravel holidayed with the couple on their yacht, named Aimée, after the initials of Misia Edwards.

Despite the initial excitement and intrigue, Misia’s second marriage was in tatters by 1907, when she lost Edwards to the alluring actress and courtesan Geneviève Lantelme. The couple married in 1909, however, in 1911, Lantelme mysteriously drowned after falling overboard from her husband’s yacht. Edwards died in 1914, taking whatever secrets he might have had about the tragic incident with him to the grave.

Misia with Coco Chanel in 1935

Misia soon fell for a new admirer, the lusty Spanish muralist José Maria Sert, a fiery man from an affluent Catalan family who made everyone else around her seem dull in comparison. Sert’s murals achieved international recognition, particularly the design that replaced Diego Rivera’s communist contribution at the Rockefeller Center. They married in 1920 and decorated their apartment on the Seine with massive pieces of rock crystal that refracted light around their rooms, which were furnished with tables of tortoiseshell and malachite.

Sert supervised the stage decoration for Les Ballets Russes, and inevitably Misia’s glittering salon became something of a home from home for an endless troupe of Russian émigrés. Misia was an early and devoted patron of the dance impresario Sergei Diaghilev. When Igor Stravinsky introduced Le Sacre du printemps to Diaghilev, it was amid Misia’s quartz and crystals that he did so. In 1916, an experimental collaboration between Diaghilev, Misia and Jean Cocteau resulted in the avant-garde ballet Parade, which combined Erik Satie’s first orchestral score with Picasso’s debut in stage décor.

Pierre Bonnard, Misia with Thadée Natanson, 1902 oil on canvas, Musees Royaux de Beaux Arts de Belgique © SABAM Belgium

A LOVELY CAT

Satie resented Misia’s tampering in his artistic process, stating: “Misia is a lovely cat – so hide your fish.” Nevertheless, Picasso became so attached to Misia that he asked her to witness his wedding to Olga Kokhlova, one of Diaghilev’s dancers. Inevitably, there was some Spanish rivalry flexing between Sert and Picasso, but Sert was soon tempted away from Misia by a younger and prettier Russian woman. Misia was extremely jealous, trying to maintain a ménage à trois for as long as her pride could bear it.

Misia’s most enduring friend, though, was Coco Chanel. Misia urged the designer to start her own line of cologne after acquiring a secret Medici recipe for eternal youth. The duo painstakingly explored designs for the L’Eau de Chanel bottle, eventually arriving at the distinctive apothecary shape. The two also experimented with illicit drugs. After her split from Sert, Misia consoled herself with morphine. Tête-à-tête, the elegant duo of Coco and Misia could be seen laughing in their first-class carriage heading to the south of France to get their fix. Cocteau dramatised their friendship in his play Les Monstres Sacrés.

Misia with Sergei Diaghilev, Coco Chanel and Contessa Marcello. Credit: Count Henri de Beaumont collection.

“Coco! That will finish me!” Misia groaned, as her overly effusive friend hurried to her bedside. In the autumn of 1950, after the last rites were delivered, Chanel took charge of Misia’s clothing and maquillage and placed a single pale-pink rose on her companion’s once-splendid bosom. For years after Misia’s death, an anonymously left rose could be found placed on her tomb at the Cimetière Samoreau.

This remarkable woman, and influential muse, was truly the cornerstone for the most gifted circle of artists Paris – and the world – has ever known.

From France Today magazine

Portrait by Vuillard

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY