The Art of Survival: The Transformation of Montmartre

Chloe Govan reveals how the poverty-stricken and persecuted in France’s past found the silver lining in their suffering, transforming it into what would one day become a world-famous art legacy

Bang! The hammer crashes down as yet another multimillion-euro masterpiece is sold at auction. Yet how many of those who covet famed French artwork know the full story – that some of the country’s most well-known pieces were born out of abject adversity? In fact, French art thrives in times of trouble. The long-standing reign of Montmartre over the art scene has gone hand in hand with strife. Moreover, its very name is indicative of struggle, translating as ‘hill of the martyrs’. In its early days, it had been segregated from Paris, standing atop a hill as an independent rural farming village in its own right. Yet in 1814, the Russian Cossacks waged political warfare on the residents, massacring the agricultural ground they depended on to survive.

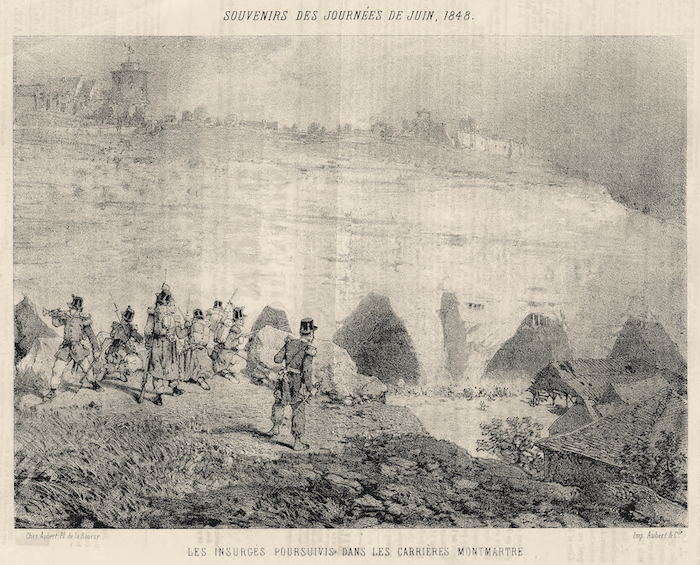

Soldiers chasing insurgents through the quarry at Montmartre in the 1800s. Photo © Brown University, Wikimedia

Even worse, less than half a century later they were doomed to be struck down again – this time by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. The effects devastated Montmartre’s population so intensely that they were forced to slaughter and eat animals from the nearby city zoo just to survive.

Two major wars in less than 60 years had reduced the village to a fraction of its former self. Many of the poverty-stricken vineyard workers, their brows furrowed and their fingers worn to the bone, became alcoholics to drown the sorrows of destitution. Drug addicts languished in the gutters, often spat on by wealthier passers-by. At a time when it was socially acceptable to regard poorhouses, mental asylums and places for the disadvantaged as tourist attractions, the destitute were seen as entertainment. With its population of drunks, orphans, prostitutes and beggars, Montmartre attracted not philanthropists but slum tourists, keen to brag to their friends about their experiences in the ‘danger zone’.

Of course, in an era when Victor Hugo had seen a starving beggar jailed for no greater crime than her desperation to grab a slice of bread, the biggest risks were for the residents. Streetwalkers struck down with syphilis lay miserably at the side of roads, too weak to move, while vermin crawled over their partially-clothed bodies, and entire streets were written off as “recesses of indescribable filth”. Tuberculosis and scabies began to spread around the crowded village too. Some houses had no glass in their windows, and residents huddled together in beds with no sheets.

Yet at this time of utter desperation, when it seemed the village could sink no lower, it found its survival instincts. For some, adversity increased their fighting spirit and awakened their creative powers. It was then that Montmartre’s transformation began. First came the dance halls, then the art that they inspired. Delivering the ultimate middle finger gesture to those who had harmed them, residents referenced the themes that had caused trauma and transformed them into success stories. For example, during the 1814 war, one of the founders of the local windmill industry had been gruesomely crucified on the sails of his own mill. His devastated brother had placed a miniature windmill on his grave – coloured crimson to represent the bloodshed – and it was the memory of this gesture that inspired the Moulin Rouge. A defiant reclamation of their village’s origins at a time when poverty and forced urbanisation threatened to destroy everything that made it unique, the club was a roaring success among locals upon its 1889 opening.

La Danse Mauresque’ by Toulouse Lautrec featuring La Goulue with Oscar Wilde in the audience. Photo credit © Wikimedia

Scenes of Nightlife

Artist Henri Toulouse-Lautrec produced hundreds of posters advertising the Moulin Rouge, which encapsulated the spirit of Montmartre’s burgeoning cabaret culture. A memorable one is ‘La Danse Mauresque’, depicting the dancer La Goulue at one of her shows, together with a bellydancer and fortune-teller and green swirls of colour reminiscent of ‘la fée verte’ – absinthe. A top-hat-clad Oscar Wilde is among the audience members.

La Goulue was something of a feminist trailblazer, destigmatising striptease when just decades earlier, some women performing it had been branded ‘prostitutes’ and thrown into asylums or jails. At a time of post-war poverty, Montmartre also welcomed her defiantly voluptuous figure, which to them represented plentiful food and the hope of better times ahead, with austerity firmly confined to the past. This society celebrated full figures just as much as Paris’s haute-couture fashion industry coveted slimline ones. La Goulue proved to be a breath of fresh air, and, having popularised the cancan, became a permanent headliner at the Moulin Rouge and a good friend of artist and regular audience member Renoir.

Toulouse Lautrec’s ‘La Blanchisseuse’ painting depicting the despair of poverty in Montmartre. Photo credit © Wikimedia

Toulouse-Lautrec ignored those who looked down on him for painting Montmartre. He had also depicted an often-penniless laundry worker he had met, who doubled as a sex worker by night, calling the painting ‘La Blanchisseuse’. It would languish in storage for years, before being sold in 2005 for a record-breaking $22.4m. It was a shame that depictions of poverty did not attract the attention of wealthy patrons at the time. Like the characters they portrayed, some struggling artists even lacked shoes to wear, but continued to pour their anguish onto their canvases.

In the same year that the Moulin Rouge opened, the Bateau-Lavoir, or ‘Washhouse Boat’, welcomed its first residents. Located just below the Place du Tertre, it featured none of the in-demand caricaturists seen there today. Instead, it was a damp, dark and unheated building housing 20 art studios specifically for the poor. Its name arose because, on a windy day, the building would creak and sway precariously, mimicking a washing boat on the Seine. In spite of its shortcomings, it attracted artists such as Matisse, Braque and Modigliani; Picasso would arrive in 1900 and stay for four years. Van Gogh was also a familiar face.

Some artists were still met with derision by those knowledgeable about the area’s troubles. For instance, one buyer of Modigliani’s paintings apparently openly admitted that he was buying the canvases only to patch up holes in the mattresses of a hotel he owned and was indifferent to what was painted on them. This type of buyer did very little to boost morale or motivation – but the tides gradually turned. And although Modigliani would tragically never live long enough to find out (he died in 1920 aged just 35), his paintings would one day be valued at millions of euros.

The popular Au Lapin Agile, a traditional cabaret which was the social scene for many artists in Montmartre’s troubled early years. Photo credit © Brenac, Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile the club scene continued to expand. Le Chat Noir was open, its interior outlandishly illustrated with “hundreds of black cats racing over the ocean, waltzing in the woods and whirling through space over red-tiled roofs”, as wrote American journalist Richard Harding Davis in his 1895 book, About Paris. Then there was Au Lapin Agile, with its iconic image of a rabbit jumping out of a saucepan on its façade, created by André Gill. The venue even inspired a Picasso painting.

At this time, the Basilica of the Sacré-Cœur was still in scaffolding, a symbol of postponed hope, but soon that too would stand tall, acting as a memorial to honour the thousands who had perished in the 1870 war. The subsequent First World War temporarily shifted the focus of the art scene across the river to Montparnasse, but the Montmartre locals remained tenaciously productive.

‘View of Montmartre With Mills’. An 1886 painting by Van Gogh who lived in Paris with brother Theo at the time. Photo credit © Wikipedia

Ultimately, it was the Second World War that would bring about the toughest challenges yet. The Nazis loathed the creative self-expression of their enemies and sought to confiscate many artworks, branding them ‘degenerate’. Ironically, not all were destroyed – they kept some for themselves. The Jewish population was worst-affected, suffering more than 38,000 home raids in Paris alone. Catholic-born Picasso escaped a German interrogation despite being described as the “most degenerate artist in the world”. He delivered a scathing retort when asked of his Nazi-bombing chaos painting ‘Guernica’, “Did you do that?”. “No,” Picasso shot back. “You did.”

The Musée de la Libération in Paris tells the story of art historian and Resistance member Rose Valland, who heroically saved thousands of France’s country’s art treasures, despite the dangers posed by the Nazi occupation. Meanwhile the Musée d’Orsay houses much ‘orphaned art’ that was rescued – more than 2,000 pieces lie here and in other museums in the city, as yet unclaimed by their rightful heirs. Amazingly, the fight for justice continues to this day – for example, Renoir’s ‘Deux Femmes Dans Un Jardin’ was finally returned to his granddaughter in 2018; it had been stolen from a bank vault when the artist fled Paris to escape the war. It is now valued at over $300,000.

An unidentified artist painted this picture of Montmartre in 1929.

Art of Survival

Many artists retreated to the south during turbulent times, hence the many art museums that can be found in Nice and other parts of the French Riviera. Matisse, wealthier than many, was already there, but he too suffered hardships which inspired his work. His daughter, Marguerite, a passionate freedom fighter, was jailed and tortured by the Nazis before narrowly escaping a train bound for a concentration camp, where she would most likely have met her death. His estranged wife, Amélie, was jailed for six months after working as a typist for the French Underground. Matisse only dodged the bullet by reluctantly signing an oath vowing never to exhibit any Jewish art.

On August 25, 1944, Paris was finally freed from the clutches of the Nazis and once more there was hope that art, too, would be liberated. It had thrived secretly and irrepressibly, refusing to be extinguished by war and destitution, and it represented a glimmer of hope amongst hatred, art over adversity. Plus the face of opposition only made their triumphs all the sweeter. The painters of Montmartre and beyond had mastered not just art, but the art of survival.

From France Today magazine

Rue Laffitte and Montmartre as it is today. Photo credit © Wikimedia Commons

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Montmarte, Moulin Rouge, Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY