Wealthy, Scandalous and Powerful: The Patrons of Paris

Marie-Laure de Noailles and Natalie Clifford Barney were both famed for their patronage of the arts but, as Lanie Goodman writes, even within the context of early 20th-century Paris, they were also notorious for their unconventionality…

“Paris has always seemed to me the only city where you can live and express yourself as you please,” wrote the American-born heiress Natalie Clifford Barney, who moved to the City of Light in 1902 and stayed for 70 years, striving to make her life a work of art through her notoriously scandalous literary salons – which rivalled even those of Gertrude Stein.

Born 26 years later, in the year that Barney came to Paris, Marie-Laure de Noailles would become one of the capital’s foremost patrons of the arts and a pioneer of the European avant-garde movement. She helped Surrealist artists, filmmakers and modern composers, but that’s not all. A pivotal, provocative figure in Parisian society, her social gatherings – both at her mansion on place des États-Unis and at her stark, white villa in Hyères, in the south of France – were always the talk of the town.

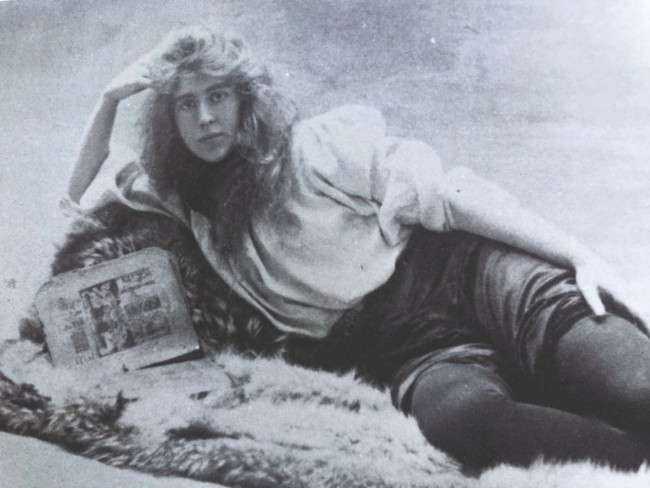

Natalie Clifford Barney, who was born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1876 and died in Paris in 1972. Image: Alamy

These two influential women overlap in time, but the differences in their artistic sensibilities were considerable. Natalie Clifford Barney, a great beauty who could translate Greek and spoke perfect French, was a lover of poetry and clung to the fashions of the Belle Époque. In contrast, Marie-Laure de Noailles, whose pale features and mop of black hair were painted by Picasso and Balthus and photographed by Man Ray, actively championed a Modernist aesthetic, as reflected in her visionary art collection. Barney would allow men of letters into her salon, but devoted herself to celebrating the women writers of her era; Noailles was known to be haughty and rude to women, preferring the company of men.

Nevertheless, both these patrons flouted social conventions and took fierce pleasure in shocking the bourgeoisie. By the same token, their generosity was focused on using their considerable fortunes to establish a cultural community. Barney and Noailles also shared similar traits: they were both elegant, highly educated, witty, capricious, flirtatious, promiscuous, imperious, extravagant – and egotistical in affairs of the heart.

Natalie Clifford Barney’s upbringing included visits to Paris, where her mother studied painting. Photo: Alamy

Dubbed “the wild girl from Cincinnati”, Barney had a less conventional upbringing than some of her contemporaries who also sought to escape America’s Protestant morality. Her mother, Alice Pike Barney, was her first model of independence. To escape her philandering, alcoholic husband, Alice would whisk Natalie and her sister off to Paris, where she studied painting (eventually under Whistler). After her father’s early death, Barney’s sudden wealth enabled her to move to Paris, where she could pursue her sapphic ideal and her love of Romantic poetry.

After briefly residing in Neuilly, she rented a 16th-century house at 20 rue Jacob, and decorated it with paintings of nymphs hanging from the ceiling.

Behind the property was a beautiful, overgrown garden and small 17th-

century temple with Doric columns that had formerly been used as a masonic lodge, with “À l’Amitié” (To Friendship) inscribed in stone.

Pagan dances in the garden at rue Jacob. Photo: Alamy

It was here, at Barney’s ‘temple to friendship’, also called L’Académie des Femmes, that women, from Isadora Duncan to Sarah Bernhardt, inspired by Pre-Raphaelite beauty, staged pagan dances dressed in flowing white gowns. Others recited lesbian poetry and then paired off and slipped away into the bedrooms. Prior to the First World War, the famed courtesan Mata Hari is reported to have pranced in Barney’s garden naked. She also wanted to ride into the salon on an elephant but the idea was vetoed by Barney, who told her, “No, there are cookies and tea, but we can’t have an elephant in my garden”.

Whether it was readings, concerts or masquerades, Barney’s salons (which might include up to 200 guests) were private, upon invitation only – and she shunned any interviews about what went on during her Friday afternoon gatherings, where tea and cucumber sandwiches, or champagne cocktails, were served. Among her many friends was the noted literary critic Remy de Gourmont, whom she supported financially asking for nothing in return. (It was Gourmont who gave her the title of “the Amazon”, which stuck.) She also entertained Jean Cocteau, Ezra Pound, André Gide, Rainer Maria Rilke, Paul Valéry, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, Djuna Barnes, Colette, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Greta Garbo, Darius Milhaud and George Antheil.

Natalie Clifford Barney enjoying some downtime. Photo: Alamy

“Natalie did not collect modern art: she collected people,” commented Solita Solano, an American writer and New Yorker journalist Janet Flanner’s partner. Apparently this was not difficult. Barney’s dazzling style bore no resemblance to some of her lesbian cohorts – ladies with high collars and monocles. In the early years, she was tall and slim, with a mane of unruly platinum hair and piercing blue eyes. “Miss Barney was not belligerent,” wrote bookshop Shakespeare and Company founder Sylvia Beach. “On the contrary, she was charming and, all dressed in white with her blonde colouring, most attractive. Many of her sex found her fatally so, I believe.”

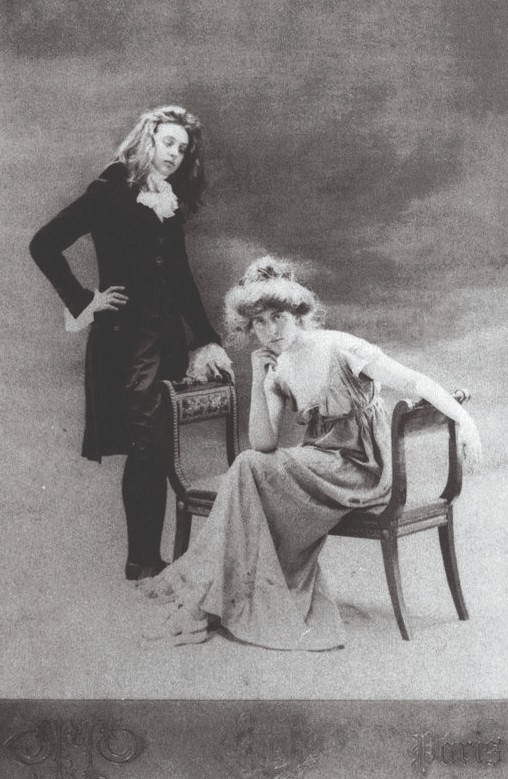

Natalie Barney posing with the sapphic poet Renée Vivien. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Described as a “female Don Juan” by her (male) biographers, Barney’s list of conquests and sometimes tragic love stories is legendary, beginning with her affair with Belle Époque courtesan Liane de Pougy. Other lovers included the British poet Renée Vivien, the American-born painter Romaine Brooks (with whom she maintained a long relationship), Dolly Wilde (Oscar’s niece) and Colette, who portrayed her in one of her novels, The Pure and the Impure. Janet Flanner chose not to include those gossip-inducing Friday afternoon teas in her Paris chronicles, however. According to Flanner, Barney “was a perfect example of an enchanted person not to write about”.

In later years, Barney’s social activities became more restricted. And, ultimately, her poems, and her book of unfinished sentences, Pensées d’une Amazone, never made literary history, whereas some of her protégées, like Djuna Barnes, or her neighbour Eileen Gray, became Modernist icons. The century had moved on; Barney remained in Paris, on rue Jacob, where she died at the age of 96.

Marie-Laure de Noailles, who was born in Paris in 1902, and died there in 1970. Image: Alamy

Marie-Laure Bischoffsheim had an illustrious maternal ancestry that was linked to the Marquis de Sade, and an unconventional grandmother, the Comtesse de Chevigné, who regularly received letters from Marcel Proust. She was from one of France’s wealthiest banking families and, at the age of seven, when her German aristocrat grandfather died, she inherited one of the greatest fortunes in Europe. After a sheltered childhood, brought up by a reclusive mother and educated at home by a British governess, she soon stood out, demonstrating a precocious intellect and reciting Baudelaire for dinner guests. A voracious reader, she was apparently more attached to books than suitors. And so, when she was 20, it was decided by the family that Marie-Laure was to be married.

When she wedded the courteous young aristocrat Charles, Vicomte de Noailles, in 1923, she forged a connection that would shape the French cultural scene for nearly half a century. An anecdote during their honeymoon cruise, described by her friend and biographer James Lord, was an early sign of her strong character. Upon arriving in Havana, Cuba, the vicomtesse refused to leave the cabin, saying she was engrossed in Freud’s Introduction to Psychoanalysis.

Marie-Laure Bischoffsheim came from one of France’s wealthiest banking families. Photo: VILLA NOAILLES HYÈRES

Back in Paris, at their hôtel particulier on place des États-Unis, the couple threw parties and costume balls, but above all, “les Charles”, as they were called, became known for their artistic munificence and avant-garde lifestyle – a reputation that began with a wedding present, a plot of land in the sleepy town of Hyères with a sweeping view of the Mediterranean Sea.

Unlike their opulent mansion in Paris (black-clad butlers, marble staircase, Corinthian columns, crystal chandeliers, a painting gallery, a garden and a salon), the viscount wanted “a small house, interesting to live in”, and hired the architect Robert Mallet-Stevens to do the job. Completed in 1925 and enlarged several times, the Villa Noailles was one of the first of its kind: an assemblage of juxtaposed concrete cubes with a at roof, filled with the latest Art Deco furniture by Eileen Gray, Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Chareau.

When Marie-Laure married Charles de Noailles the couple were gifted a parcel of land at Hyères, upon which they had a house built. Photo: VILLA NOAILLES HYÈRES

Eccentric touches flourished, from a special room set aside for flower arranging to electric clocks in every room. Charles, also an avid horticulturist, commissioned a Cubist garden, a triangular chequerboard of vegetation created by Gabriel Guévrékian to resemble the prow of a ship – a monumental bronze

sculpture by Jacques Lipchitz rotated on a motorised pedestal in the place of

the figurehead – and adorned with works by Giacometti and Zadkine.

Other extravagant features included 15 guest rooms (all equipped with wildly expensive private bathrooms), rooftop sleeping porches for balmy nights, a covered swimming pool, a squash court and a gym with an in-house private instructor. In his journal, André Gide listed some of the amusing highlights of his stay, which included “gymnastics, swimming in a vast pool, new games whose names I don’t know, played with a shuttlecock, balls, balloons of every description…”.

The viscount and viscountess’s charmed circle of friends included the likes of Buñuel and Dalí – for whom the Noailles financed L’Age d’Or, the scandalous sequel to their movie Un Chien Andalou. When the film was shown to a group of aristocratic guests at the Noailles mansion, it stirred a veritable scandal. It was banned a week later and confiscated by the authorities.

The author André Gide remembered “playing games whose names I don’t know” on visits to the house. Photo: ,VILLA NOAILLES HYÈRES

In 1929, when Noailles found her husband and gymnastics teacher in bed together, the couple parted amiably and began to live separate lives. Charles went to live in Grasse, where he cultivated his passion for gardening and took charge of the upbringing of their two children.

Meanwhile, she carried on with her role as a patron of the arts, which often coincided with a lifelong pursuit of struggling or ill-suited lovers – beautiful young men who nearly ruined her – beginning with young Ukrainian musician and composer, Igor Markevitch, a supposed prodigy who had collaborated with Diaghilev but never made his mark. In later years, she befriended the then unknown American composer Ned Rorem and gave him a room with a piano in her Paris mansion, where he stayed for five years.

Dubbed “the queen of café society”, she became more eccentric as the years passed, abandoning her Chanel suits and bags for voluminous, market-bought peasant skirts and wicker baskets. Her artistic air for the new remained sharp, however. In the 1960s, Noailles was one of the first to buy César’s compressed car. She was daring in her taste for art, but was also not one to be cowed, even when, during the Second World War, two German officers burst into her bedroom, presumably to arrest her. “Gentlemen, haven’t you been taught to take off your hats in a lady’s room?” she snapped. “Emma, bring me my tea.” The officers turned and left.

She died of pulmonary edema in January 1970, at the age of 68; Barney outlived her by two years.

The Cubist garden designed by Gabriel Guévrékian for Villa Noailles, today sans statues. Photo: Shutterstock

DID YOU KNOW?

After a full renovation in 2003, the Villa Noailles continues to support the arts by hosting annual events such as a festival of young fashion designers, as well as exhibitions in photography, architecture and design. You can also visit the former 1895-built Noailles mansion at 11 place des États-Unis, which has been converted into the sumptuous Maison Baccarat (redesigned by none other than Philippe Starck) and houses a crystal museum and restaurant.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *