Commemorating the Fallen: The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission has been toiling tirelessly in the shadows since the First World War. At long last, its incredible restoration work is being thrust into the spotlight at a new visitor centre. Jon Palmer heads to Beaurains to meet the unsung heroes on a mission to honour the memory of 1.7 million casualties of war

Shortly before the Commonwealth War Graves Commission was due to open its new visitor centre at its workshop outside Arras, they found another body. Work had been going on, as it does, fixing the perimeter fence at one of the many graveyards in the region, when the workers inadvertently unearthed the body of another fallen soldier, just outside the cemetery boundary. On this occasion, the CWGC was presented with a fairly straightforward task: the body had to be identified and then simply moved inside the fence; job done.

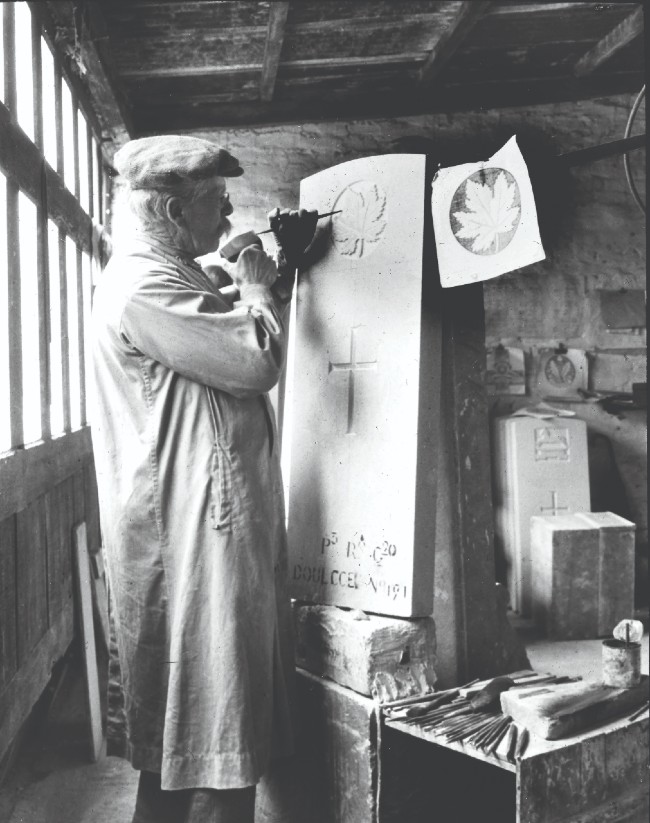

An engraver chisels a maple leaf into the grave of a Canadian soldier in 1920. © CWGC

Imagine if you’d been working on that detail. It’s the sort of thing you’d talk about for years – “I was fixing this fence and I dug up a body” – but actually it’s pretty routine around here. In fact, not long before that happened, some council workers were digging up a road… and they found two bodies. At that point the CWGC had to be called and the council workers had to find something else to do until the organisation’s trained exhumation officers had come in, recorded and reported any evidence that might lead to an identification, safely removed the remains (which probably wouldn’t have been in very good condition) and the scene had been cleared.

Early CWGC staff. © CWGC

There are, as you know, a lot of dead bodies around here. You can’t travel very far around this part of northern France without finding a corner of a field that will be forever England. Or Canada, or Australia… Or Germany. In places there seems to be a graveyard around every corner. They’re not small ones either. And this is just the people they’ve found. When you go and visit the CWGC they’ll have new stories of new discoveries – and they’ll tell you that although they are finding fewer bodies these days, that’s just because time and mud have buried them deeper, not because their work is nearly done. They are still finding about 40 a year, but even at that rate, they have calculated that it would take another 4,300 years of unbroken work before they could close the CWGC centre and congratulate themselves on a job completed.

A woman plants flowers at St. Barnabas churchyard in Essex. © CWGC

SLEUTHING WORK

And every single time they discover a body, some considerable sleuthing work has to be done. Just because the soldier was wearing that helmet when he died doesn’t mean that he belonged to that regiment, or even that army: men traded equipment all the time, or found on a dead man a better helmet than the one they were wearing… (German helmets were best.)

An Arnhem veteran pays his respects to his fallen comrades. © CWGC

A name tag is a good clue, as is a pair of boots (apparently they didn’t trade boots very often), but that doesn’t make anything absolutely certain either. The ability to reliably test DNA has been a major breakthrough; but while that means more positive identifications can be made, it also presents a whole set of jobs. Sometimes, a body will have been “identified”, a headstone made, a grave dug in the appropriate place, a ceremony performed… and then they’ll find they got the wrong man. The soldier they thought was buried there, turns up somewhere else, and the work begins again. And this can happen anywhere: bodies are repatriated.

Gardeners spruce up the 7th Field Ambulance Cemetery in Turkey. © CWGC

Not every Commonwealth soldier who was killed in the two World Wars died in France. Many did, but the CWGC’s remit is global. The organisation might have to go to Fiji, or wherever, and gently explain that actually they’re going to have to remove that headstone and dig up that grave, because there seems to have been a mistake. CWGC’s responsibility is to ensure that no soldier is forgotten. And all that work ends up here, in the CWGC centre in Beaurains, near Arras.

War widows circa 1922. © CWGC

The Commission’s headquarters are in Maidenhead, and that’s where the paperwork is done (and redone) but all the actual work – cutting the headstones, engraving the headstones, making the gates and fences for all the Commonwealth war graves, not just in northern France but all over the world – it all happens here.

A PLACE LIKE NO OTHER

While you’re in Pas-de-Calais, you’ll probably visit (among other places) Vimy Ridge, the Canadian memorial famous the world over for its glimmering white stone. This was recently renovated; it got fixed up and cleaned quite extensively – they even had to reopen the quarry in Croatia where the stone had come from to get some more to do the job. And who did all that? The CWGC.

The unveiling of the Neuve-Chapelle Memorial in 1927. © CWGC

But if you travel to Canada itself, or South Africa, or India, and you come across the tomb of a repatriated soldier, the CWGC not only put him there but goes back periodically to check that the weeds have been cleared, and that the inscription is still legible (there’s a very specific criteria for measuring this). And if it’s not all correct, and the job can’t be done on-site, the work ends up on the to-do list at Beaurains.

The Commission’s preservation and restoration mission extends as far as Thailand. © CWGC

And now you can actually come here and see all that work being carried out, from the most prosaic to the most poetic tasks.

You can see the gardening tools being cleaned and repaired for service in the graveyards here; the commemoration text being engraved on a headstone bound for some distant land where there lies the body of someone you would otherwise never have heard of. It’s a place like no other. You visit lots of workshops around France and see many interesting things being made, but you’ll never visit one quite like this.

Hooge Crater in Ypres. © CWGC

CWGC ESSENTIALS

ADDRESS

CWGC Experience, 7 rue Angèle Richard, 62217 Beaurains

CONTACT

Head Office (Maidenhead) Tel. +44 (0)1628 634221; [email protected]

CWGC Gardeners in 1929. © CWGC

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission honours the 1.7 million men and women of the Commonwealth forces who died in the First and Second World Wars. Its work includes building and maintaining Commonwealth cemeteries and memorials at 23,000 locations in more than 150 countries and territories, and also preserving and updating its extensive records and archives. It is funded by the governments of the Commonwealth nations and by donations.

It began as the brainchild of one man, Sir Fabian Ware, who joined the Red Cross during the First World War and became determined to ensure that those who had died would not be forgotten. His work was officially recognised in 1915 as the Graves Registration Commission, and in May 1917 the Imperial War Graves Commission was established by Royal Charter.

Sir Fabian Ware

By 1918 some 587,000 graves had been identified and a further 559,000 unknown casualties had been registered. The architects Sir Edwin Lutyens, Sir Herbert Baker and Sir Reginald Blomfield started designing and constructing the cemeteries and memorials, while Rudyard Kipling was tasked as literary advisor to recommend inscriptions.

THE PRINCIPLES OF THE CWGC ARE THAT:

-Each of the dead should be commemorated by name on the headstone or memorial

-Headstones and memorials should be permanent

-Headstones should be uniform

-There should be no distinction made on account of military rank, race or creed

The CWGC Experience

THE CWGC EXPERIENCE

The CWGC Experience visitor centre is open from Monday to Friday, 10am-4pm. It is closed

on French public holidays and at weekends, and it will also be closed during December and January for maintenance. Advance booking is only required for larger groups. This is, of course, still actually a place of work, so there wouldn’t be much point in coming here on Saturday or Sunday. But it is also a place of public service, so during the week, when it is open, parking is free and so is admission, though you are gently invited to make a cash donation as you enter the workshop area to begin your tour – or you could buy something at the gift shop.

From the car park, it just looks like a large workshop with a nice new building attached to the front, which of course it is, but as the automatic glass doors open you catch your first glimpse of the work they have done to convert this atelier into a visitor centre.

You can now see craftsmen hard at work at the new CWGC Experience visitor centre. © CWGC

In the entrance foyer, the first thing that greets you (after the friendly smile from the volunteer at the desk) is a large map of the world on the far wall indicating all the places around the globe where the CWGC is operating. This is the room where, as you peruse the gift shop, you’ll have the chance – before or after you do the tour – to chat to the helpful and knowledgeable staff, many of whom are history or archaeology postgraduate students on a six-month placement, and all of whom speak English, often as their mother tongue.

Engraver at the new CWGC Experience visitor centre. © CWGC

The tour itself is self-guided (free audio guides are available at the welcome desk) so you can spend as much time here as you like, though 45 minutes is the figure they quote. You will want to allow more time if you wish to talk longer with the staff or avail yourself of the facilities for searching the CWGC records for, perhaps, a lost loved one.

From France Today magazine

After his tour of the visitor centre, Jon Palmer headed to Vimy Ridge. Photo: James Ruddy

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Jon Palmer

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY