The Route of the Cathars

Bewitching as it is, this region has a grisly and turbulent past involving religious persecution. Susan Aran follows in the footsteps of the Cathars as she explores this part of Languedoc’s fascinating history

Cathar country in the Languedoc has a brooding, enigmatic presence: hilltop settlements and atmospheric medieval citadels, expansive scrubby landscapes and, of course, the fortified Cathar city of Carcassonne. But to truly appreciate the area’s beauty today, you need an understanding of a brutal and bloody past that caused a religious group to flee. The route they took is still a popular trail.

After a weekend visit to Carcassonne, I decided to head southwest and stop at the first hilltop village that beckoned through the darkening sky of a summer storm. My guidebook explained that the citadel of Fanjeaux was once a very important 13th-century Cathar centre with over 3,000 inhabitants. Unlike Carcassonne, which has been grandly rebuilt, Fanjeaux is a ghost town. Once surrounded by a moat and safeguarded by 14 towers, almost nothing of it remains today.

The small commune of Cucugnan lies in a valley in the Corbières mountains. Photo: Sue Aran

MASSACRE OF THE INNOCENTS

I found a seat in a café, ordered coffee and continued to read. During the 12th and 13th centuries, more than half a million men, women and children in this area were massacred. It was here that the Roman Catholic Church engaged in the Albigensian Crusade, a 20-year war against a group of ‘heretical unbelievers’ known as the Cathars. This resulted in the eradication of an entire civilisation in the area broadly bordered by the Mediterranean Sea, the Pyrénées, and the Garonne, Tarn and Rhône rivers, known as the Languedoc.

Looking up, I returned a greeting to a man who’d just entered the café. He was, it turned out, Keith Bell, an artist from England who’d recently settled in Fanjeaux with his wife. After exchanging stories of what brought us both to France, we discovered we shared a common interest in the popular books Labyrinth, The Da Vinci Code and the controversial Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. These were all written about this area and its fascinating history, including that of the Knights Templar, who lived in harmony with the Cathars.

The route des Cathars in the Cucugnan Valley. Photo: Sue Aran

Founded in around 1119 AD, the Order of the Knights Templar was a religious group of men that was formed to defend the Kingdom of Jerusalem and protect Christian pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land. Over the next two centuries, grateful Christians donated their land and their money to the Order, making the Knights not only powerful financiers, but also guardians of untold valuables. They were reputed to possess something of extraordinary sacred value – the Holy Grail. According to legend, the Holy Grail was believed to have been entrusted to the Cathars, becoming part of their treasure. It was mysteriously spirited away during the Siege of Montségur, the last Cathar stronghold, which fell after a 10-month blockade in 1244.

These kinds of romanticised myths, tall tales and conspiracy theories made for fascinating reading and conversation and, following our lively tête-à-tête on the subject, Keith invited me to meet his wife and see some of his paintings. Before we parted, I purchased one, a colourful landscape of the village of Fanjeaux at dusk.

A detail from British artist Keith Bell’s atmospheric painting of Fanjeaux

Sometimes the incalculable cruelty of man is beyond understanding, so it was hard to visualise the odious events that took place amid such majestic scenery. The Cathar heartland is a surprisingly affecting place, so I extended my journey and drove south into the mountains in a bid to better comprehend the historical drama that unfolded there almost eight centuries ago.

In the early Middle Ages, the Languedoc was not part of France. It was an independent area comprising a handful of city-states, each with its own rulers, the most powerful of whom were the Counts of Toulouse. During the 12th century, the Cathar religion flourished in this area noted for its high culture, sophistication, religious tolerance and liberalism. The most highly educated people spoke Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, and Occitan, the language of the songs and poetry of the troubadours (travelling musicians).

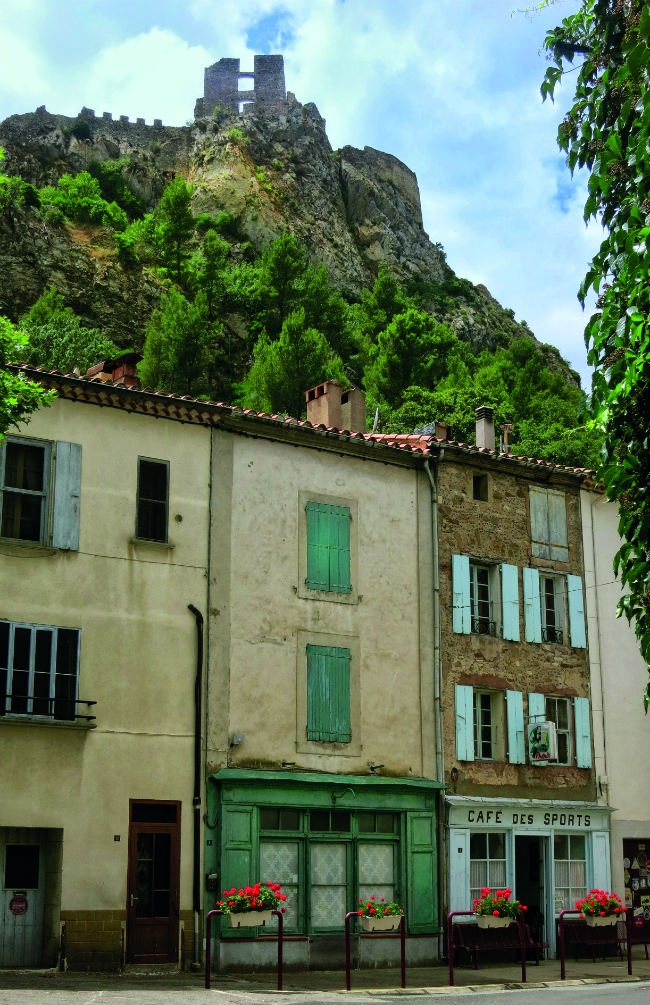

The Château of Foix overlooks the town of the same name. It withstood the attacks of Simon de Montfort between 1211 and 1217, during the Albigensian Crusade. Photo: Sue Aran

The Counts of Toulouse, among many other noble families, were either supporters of, or were Cathars themselves. Some historians assert that the Cathar philosophy and religious beliefs, which included Islamic and Judaic perspectives, already existed in Persia and the Byzantine Empire by the 11th century. Others believe that this Cathar ideology originated in the Balkans advancing through Italy to southern France. Regardless, these ideas filtered west on trade routes via Marseille to the Pyrénées.

By the turn of the 13th century, Catharism was the major religion in the area. For a Cathar, Christ was a human being and therefore directly accessible, negating the power and purpose of the priesthood, something the Catholic Church found intolerable. Many Catholic texts of the time highlight the dangers of Catharism replacing Catholicism completely. The popularity of their ideals, combined with the fact that many Cathar nobles in the Languedoc owned vast tracts of extremely valuable land, further incited the wrath of the Catholic church.

The hilltop Château de Puivert in the Aude overlooks a village and lake. Photo: Sue Aran

REFUSAL TO CONFORM

The Cathars maintained a standard church hierarchy and practised a range of religious ceremonies. Appalled by the intemperate popes and their corrupt clerics who ignored their parishioners and ran businesses on large estates, they refused to accept the authority of the Old Testament. They believed the Last Judgement had already occurred and the guilty were living in hell. They did not bow to images of Christ, believing Jesus was a mortal being who died on the cross for the principle of love.

They disavowed the practices of communion, tithing, funeral rites or penances. They were strict about biblical injunctions – notably those about living in poverty, not killing, not telling lies nor swearing oaths. They believed in reincarnation, equality between the sexes, contraception, and veganism, and accepted euthanasia and suicide as part of life.

Château de Quéribus on the Cathar Route is one of five strategically placed to defend the French border against the Spanish. Photo: Sue Aran

In 1208, the head of the Catholic Church, Pope Innocent III, called for a formal Crusade against the Cathars. Following swiftly on the heels of the Crusades in the Holy Land, citizens were eager for this new opportunity for glory. The Church promised rewards for the fighters: remission of all sins, expiation of penances, assurances of places in Heaven and all the plunderable booty they could gather, in return for 40 days of service. Thousands of fearsome warriors from northern France and Germany joined Pope Innocent’s holy army led by the sadistic Simon de Montfort. Among his many other atrocities, de Montfort ordered his troops to gouge out the eyes of their prisoners and cut off their noses and lips before sending them back to their villages as warnings.

Château de Puivert. Photo: Sue Aran

When the town of Béziers was attacked, it was filled with Christians as well as ‘heretics’. One of de Montfort’s crusader monks, a Cistercian abbot named Arnaud Amaury, was asked, “How shall we know who to kill?”. He replied: “Kill them all. God will know his own.” Any town that resisted was taken by force and all of its inhabitants killed, either by sword or burning at the stake. Fleeing persecution, the Cathars embarked on a 200km trek from the town of Foix, 90km south of Toulouse, along the border between France and the Kingdom of Aragon (now part of northern Spain), to either Port-la-Nouvelle north of Perpignan or Berga in what was then the Catalan lands. Their route is now dotted with the ruins of châteaux in which they took shelter during their flight: Aguilar, Padern, Quéribus, Peyrepertuse, Puilaurens, Puivert, Montségur and Ermitage Saint-Antoine de Galamus among others.

Jacques Fournier, Bishop of Pamiers, who later became Pope Benedict XII of Avignon, was meticulous in keeping the Inquisitional records he extrapolated from the last bastion of Cathar heretics in Montaillou, a village between Toulouse and Andorra. Documents found in the Vatican archives and known as the ‘Fournier Register’ were translated and published as Montaillou. This is a fascinating social history, a medieval soap opera peopled by debauched priests, unfaithful châtelaines and scheming peasants.

Perched high on a limestone peak is Château de Padern. Photo: Sue Aran

TOTAL ERADICATION

By the end of the 14th century, Catharism had been completely erased from the landscape. Prior to the Albigensian Crusade, the Languedoc, under the Counts of Toulouse, had been the most civilized land in Europe. Now it was the most brutalised and in ruins. Dominic Guzmán (later Saint Dominic), a Spanish fanatic who founded the Dominican Order, lived in Fanjeaux for nine years. His sole purpose was to wipe out the last clandestine Cathars from the area, which he did.

Château de Peyrepertuse. Photo: Sue Aran

Today the Route of the Cathars is a relatively undemanding, yet spectacularly scenic route of ancient châteaux ruins perched on perilous, limestone crags above lush Alpine meadows, dense forests, dramatic gorges and thermal springs, that make this part of southern France one of the most popular destinations. It comprises part of the 28,079 square miles of the newly formed region of Occitanie, formerly the Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrénées regions. The route can be traversed by car in a day, cycled or hiked in under two weeks. You’ll discover wonderful local food, robust wines and maybe a glimpse of the past. Though much of the rich culture of the Languedoc was lost, its beauty and spirit have remained.

Château de Puilaurens, owned by the King of Aragon, was a safe refuge for the Cathars fleeing persecution. Photo: Sue Aran

ESSENTIALS

For more information on the Cathars see www.audetourisme.com

GETTING THERE

The city of Carcassonne is considered the gateway to Cathar country. It is reached by train (the TGV from Paris to Toulouse), then rental car. The local airport is served from England by Ryanair and Air France from French locations. There are over 32 historical sites associated with the Cathars.

From France Today magazine

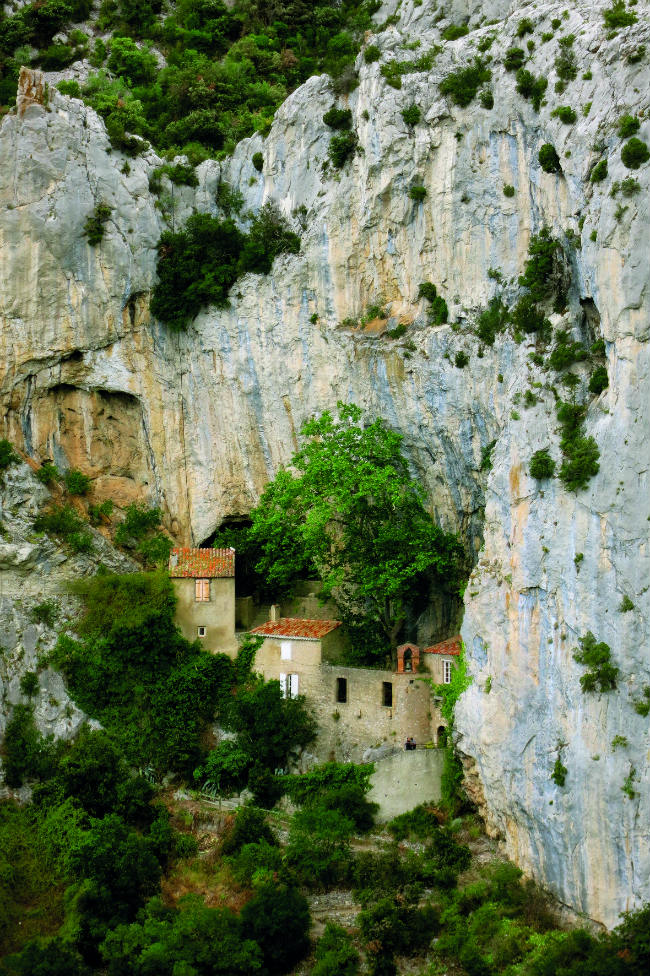

L’Ermitage St Antoine de Galamus, which sheltered fleeing Cathars, nestles in the Gorges de Galamus and is protected to the rear by sheer rock faces. Photo: Sue Aran

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Sue Aran

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY