Bayeux and Caen: Normandy’s Historical Hubs

Travelling by boat still carries with it an air of adventure, even if the overnight journey across the English Channel is rather more modest than the epic sea voyages of yore. Yet an unusually rough crossing and the resultant broken sleep had left me queasy and bewildered as I stumbled back onto dry land at Caen-Ouistreham port, seven hours after leaving Portsmouth. It was 6am and the sun had only been up a few minutes longer than I had, with the morning light glinting off a grey-blue sea.

At least at this hour the boulangerie’s pastries were delectably warm, straight from the oven, and as I tucked in I orientated myself, noting that the beaches which hosted World War 2’s D-Day Landings were just a stone’s throw away. However, the reason for my visit to Caen was to discover the earlier roots of Norman history – I was going to meet William the Conqueror.

Caen: medieval to modern

At first glance, Caen’s medieval heritage is obscured by the siege of grey, 1950s tower blocks which gradually replaced the piles of rubble that were left by World War 2. Its history is hidden between the cracks in the concrete and in the handful of higgledy-piggledly, timber-framed houses which have been left wedged between modern builds, their slanted beams betraying their fragility as they lean against the younger edifices.

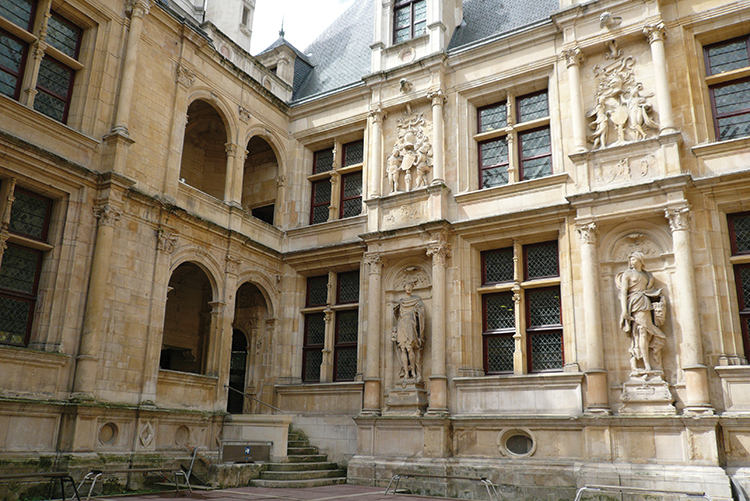

Between June and August of 1944 some 75% of Caen was razed to the ground by heavy aerial bombing, but the city’s major landmarks survived – to help orientate Allied pilots through unfamiliar French territory, rather than out of a concern for architectural heritage. Following the war, much of central Caen was rebuilt in harmony with the city’s 15th- and 16th-century Italianate mansions, which used local limestone and were decorated by Florentine artisans. Some of these miraculously survived the bombings, including the ornate Hôtel d’Escoville, now the tourist office.

Hôtel d’Escoville

Caen’s overarching visual identity may be borne of post-war pragmatism but its soul is defiantly medieval, albeit with a Renaissance flair. Happily, the major legacies of the Duke of Normandy’s reign are in pristine condition and open to visitors: Caen Castle, the Abbaye aux Dames and the Abbaye aux Hommes, all of which were commissioned by Guillaume himself.

Guillaume le Conquérant

Born on Christmas Day in 1028AD, William the Conqueror initially went by the far less noble name of William the Bastard, being the result of a fling between Robert ‘the Magnificent’ and his mistress.

Succeeding his father as Duke of Normandy at the age of 20, Guillaume became the Norman king of England following the Battle of Hastings in 1066AD. William married his distant cousin Matilda of Flanders, although the Pope refused to officiate as they were related. The marriage was eventually recognised on the condition that the couple founded two Benedictine abbeys in Caen: the Abbaye aux Dames for women and the Abbaye aux Hommes for men. After a long marriage and at least nine children, they were laid to rest in the very Romanesque abbeys that had established their union in bricks and mortar.

Abbaye aux Hommes, Caen

William’s tomb sits before the gilded altar of the Abbaye aux Hommes, beneath its towering stone vaults. It’s a modest, flat tablet embedded in the marble-tiled floor and looks small considering the alleged size of the king himself. At nearly six feet in height, William was incredibly tall for his time and I was amazed to learn that, upon his death, the king was so obese that the weight of his coffin repeatedly broke the ropes holding it up during its transportation to Caen from Rouen, where he’d been killed in battle.

Upon his coffin’s arrival at the abbey, the tomb was found to be far too small for his enormous form. The attendants tried to push the corpse’s head and feet to the sides, to cram it into the inadequate space, to no avail. I didn’t press my tour guide for the gory details of how they eventually managed to get him in there, but I was assured that it isn’t a pretty story…

Across the abbey’s leafy cloister lies the former monastery, which has been Caen’s Hôtel de Ville since 1965. Its beautifully restored rooms are used for civil partnership ceremonies and regional events, with the big receptions usually held in the grand dining hall. Along the wall is a vast, 18th-century painting of Guillaume entering the Battle of Hastings, bizarrely dressed as a Neo-Classical Roman emperor and reminding visitors of the inextricable ties between Normandy and the UK, whose shared history was so defined by the man known as William the Conqueror.

Bayeux: embroidering history

Caen’s historic architecture may have been virtually obliterated by the Allies’ bombs but Bayeux, as the first French city to be liberated (on June 7, 1944), was lucky enough to remain wholly intact. That remarkable fact makes it one of the most picturesque cities I’ve ever visited, one with an easily-walkable, cobblestoned centre lined with timber-framed, 17th-century houses and shaded by shop awnings framing pretty boutiques and dinky tearooms. The traditional local craft is lace, and artisan makers thread delicate table linens and silken handkerchiefs in street-side fabric shops, with stylish Frenchwomen slowing their stilettoed pace to linger at the window displays as they pass by.

A detail of the Bayeux Tapestry

An audio-guided explanation of the Battle of Hastings, as related in the tapestry, takes 20 minutes, and I was taken aback by the apparent modernity of the figures depicted. The artwork isn’t only visually arresting and beautifully coloured, its 50 scenes are also amusingly playful. Stances and facial expressions are so relatable that the medieval saga hardly feels like it took place over 1,000 years ago.

Bishop Odon, William the Conqueror’s half-brother, most likely commissioned the Bayeux Tapestry to decorate Notre-Dame de Bayeux during its consecration in 1077AD. I concluded my trip with a visit to the cathedral, the style of which is a Romanesque-Gothic crossover owing to a semi-rebuild in the 12th century.

Bayeux cathedral

This grandiose, intricately carved stone edifice has borne witness to some of the most poignant moments in French history. Here, King Harold bequeathed the English crown to William the Conqueror, prompting the Norman invasion when the oath was breached. In 1794 a ‘liberty tree’ was planted at the cathedral’s feet as Bayeux’s citizens sang La Marseillaise in joyful celebration of their freedom from monarchic rule. And centuries later, the cathedral’s interior was completely stripped as the Occupation and Battle of Normandy threatened its precious heritage. Yet Bayeux cathedral stood proudly as General Charles de Gaulle marched, triumphant, through the liberated city in June 1944, delivering two exultant speeches just streets away.

Not only is Bayeux a city of breathtaking beauty but it’s also an unparalleled cultural gem, spanning each period of French history and taking centre stage at some key moments. I originally visited Caen and Bayeux to become acquainted with William the Conqueror, but soon realised that his story is just one chapter in Normandy’s fascinating tale. Which calls, I suppose, for another visit…

Essential information..

GETTING THERE

Brittany Ferries sail to Caen up to three times per day from Portsmouth – it’s a six- or seven-hour crossing.

WHERE TO STAY

Le Lion d’Or, Bayeux

The World War 2 headquarters of the British press, this hotel has hosted such prestigious guests as Winston Churchill and General Dwight D Eisenhower.

WHERE TO EAT

La Manufacture, Caen

A brand new, classy joint serving modern, creative and seasonal French cuisine.

CONTACT

Calvados Tourism

www.calvados-tourisme.co.uk

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *