A Road and Rail Adventure in Green Auvergne

There’s more to the Auvergne than volcanoes – find out on a road and rail trip around the region.

“With the fog, we’re not lost, but I don’t know where we are any more.” So said aviator Eugène Renaux as he flew a flimsy biplane from the Île-de-France to the Puy de Dôme. He and his passenger, Albert Senouque, were following railways and roads to Clermont-Ferrand to claim the 1911 Michelin Grand Prix, а competition engineered by André Michelin to advance passenger aviation.

Fast forward a century and a bit, and France has announced that some domestic short-haul flights are banned. The irony is not lost, standing before the statue of Renaux at the spot where he touched down on the Puy de Dôme, the empty runway of Aéroport Clermont-Ferrand just the other side of the volcano. Or, indeed, that Renaux and Senouque followed roads and railway lines to reach their destination.

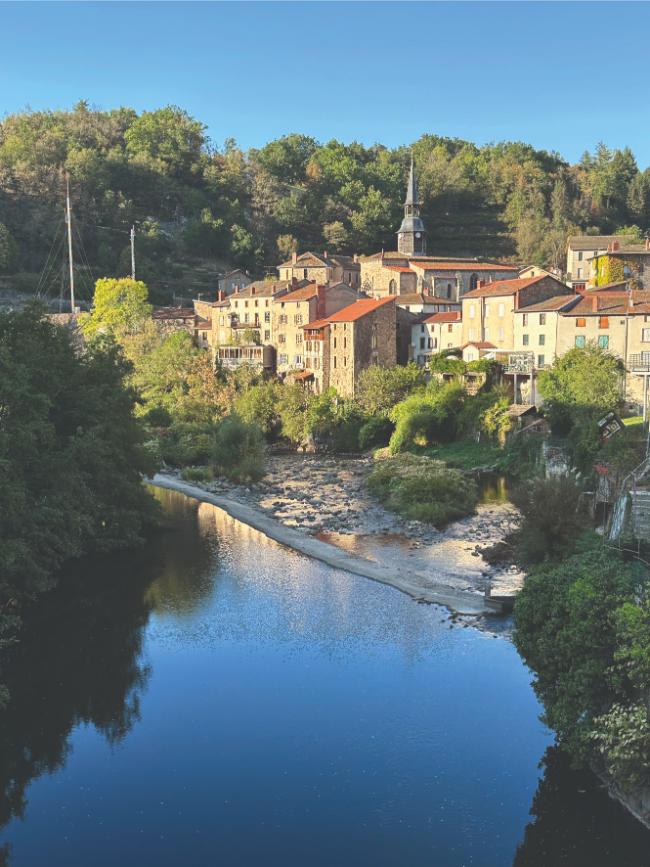

Moulins and the River Allier © Caroline Mills

France’s last wild river

It’s the same for me on a road-and-rail trip around the Auvergne. There’s no fog and I’m not lost, but I don’t know exactly where I am. And that’s fine by me. Because there’s some unsung countryside within the Auvergne that is often overshadowed by its volcanic core – and it’s worth getting lost in.

I begin my tour in Moulins, a designated City of Art and History. There’s plenty of it, too, as a walking tour around the town of cream stone beneath sepia-coloured pantiles illustrates. Statues of ordinary folk from the Bourbonnais countryside on the Cathédrale Nôtre-Dame indicate the town’s historical location, as do the Château des Ducs de Bourbon and the elaborate Musée Anne-de-Beaujeu, housed in the Renaissance palace commissioned by Anne de France in 1500. And on the Jacquemart tower, you can watch as figurines of husband and wife Jacquemart and Jacquette and their two children, Jacqueline and Jacquelin, strike time.

I stride out across the 13-arched Pont Régemortes over the River Allier to visit the Centre National du Costume et de la Scène. This extraordinarily good museum is vast in scale, showcasing the conception and creation of stage sets and offering themed exhibitions on costume. It also houses the Nureyev Foundation collection, with a fascinating exhibition about Rudolf Nureyev’s life and career as a dancer.

I return to the city centre via the Pont de Fer, a former railway bridge that has been renovated as a traffic-free cycle and walking route offering remarkable views of the river and the city. It’s my first flirtation with the Auvergne’s railways.

To describe the Auvergne region simplistically, it’s like a giant T of gentle landscapes, with the Allier department forming the cross-piece and the Allier valley its stem. Either side are two high-terrain massifs, the Parc des Volcans d’Auvergne to the west and the Parc naturel régional Livradois-Forez to the east.

Olliergues, in the Parc Naturel Régional du Livradois-Forez © Caroline Mills

It’s down the stem of the T that I follow the river upstream, along the Via Allier. This 435km cycle route traverses the Auvergne north to south, taking in country lanes and riverside greenways. South of Moulins, the cycle route passes by the Réserve Naturelle Val d’Allier, protecting the landscape and wildlife of the Allier, often referenced as the last wild river of France. Ten access points within the reserve provide opportunities for circular walks, canoeing and nature hides, with one of the prettiest viewpoints at Châtel-de-Neuvre. Here, as at Moulins, it’s possible to see the Allier’s composition of shallow rivulets and sandbanks, much like its parent river, the Loire.

South of the reserve is Billy, a medieval Petite Cité de Caractère, upon a hilltop surrounded by gentle, green suede undulations. A substantial 12th-century fortress dominates, with rose-clad houses encircling its base rather like ramparts. A couple of circular walks through the countryside set off from the castle, as does the Via Allier, a 13km section of which runs riverside along a traffic-free voie verte to Vichy. Cycling this stretch is popular.

Beyond the spas of Vichy, and with the repellent taste of its hot and fizzy Célestins water obtained from its source still in my mouth, I head into the hills of the Parc naturel régional Livradois-Forez. My route leaves behind the Via Allier and follows its tributary, the River Dore, instead, at first along an open valley before climbing into oak-lined guttering, funnelling the shallow salmon river along a narrow gorge.

The road snakes amongst forest, passing through Olliergues (utterly beguiling when backlit by a setting sun) and along the river passing beneath the Pont Romain, a medieval bridge that now leads into someone’s garden. Then I reach Ambert, the centrepiece of the park, which is known for paper manufacturing and its AOP Fourme d’Ambert cheese. Less well-known, as a Plus Beau Détour, is its rotund town hall, which is unique in Europe. The tourist office at Ambert recommends I take the main road (the D906) to Brioude because it’s “trés jolie“. More than jolie, the scenery is sublime. Cattle calmly chew the cud, sitting in the autumn sunshine as I continue by road along the wide, very flat Dore valley, either side of which lie wooded hills. In summer, it’s possible to take the tourist train, which terminates at La Chaise-Dieu, a pretty, historic village dominated by its abbey. Here, I turn west, stopping at – such is their beauty a string of ungentrified villages each with a rustic barn, an antiquated tractor and a witches’ hat church apiece. Javaugues offers distant views of volcanoes.

Crossing a much smaller River Allier, having descended from the hills of the Livradois-Forez, I’m tempted by signs for the Haut Allier and the chance to follow the Via Allier cycle route again. But Brioude beckons on the horizon. Another Plus Beaux Détours town, its central basilica is monumental. Inside are unexpected frescoes depicting The Creation, covering walls and pillars, while smooth black pebbles create artistic mosaic patterns on the floor. The basilica’s stained-glass is far from the usual religious scenes, offering instead vivid abstract art by Korean-born artist Kim En Joong.

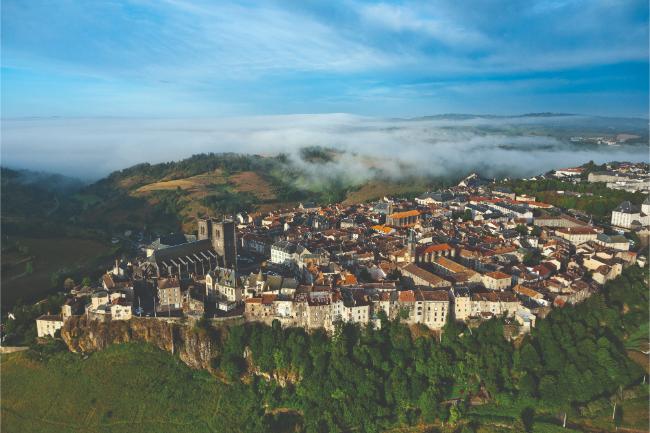

Saint-Flour © Caroline Mills

All aboard

Leaving the Allier behind, I cross the gentle-going Monts de la Margeride to Ruynes-en-Margeride where I pick any road to follow. Like Renaux, I don’t exactly know where I am any more, but I’m very happy with my selection, for I end up in Chaliers, a tiny clifftop village perched above the River Truyère, which bumbles along the valley below. The river leads, on a labyrinthine route, to the Viaduc de Garabit, which is one of my reasons for visiting the Auvergne. The viaduct, which towers above the Truyère valley, is a masterpiece by Gustave Eiffel, who designed the rail crossing several years before his famous Parisian landmark.

I wait and watch as the sun glows and then sets, turning the flamboyant, red-riveted structure, in stark contrast with the brilliant blue river and verdant wooded slopes, to a silhouetted web of iron. Just like the tower in Paris some 530km north, lights come on as darkness falls. I listen to rolling stock – the only train that day – trundle across the viaduct with that celebrated staccato rhythm that all trains make, as though punching out an emergency Morse code message. And there’s every reason for the SOS: the line between Saint-Chély-d’Apcher, just across the departmental border in Lozère, and Saint-Flour, in the Cantal department, is under threat of closure. Friends of the Garabit are concerned that if the line closes, there will be no reason to keep the viaduct maintained. Hence, a series of slow tourism initiatives enticing visitors to ride the train for the viaduct-high views and then cycle back to your starting point. Sadly, the line is closed to passengers the day I visit.

Like this? You might enjoy our in-depth story: The Viaduc de Garabit, a Gustave Eiffel Masterpiece

Viaduc de Garabit © Caroline Mills

On the road again

My exploration continues by road through the Vallée de la Haute Truyère to Chaudes-Aigues, a mountain village tucked into a valley, which offers a rustic version of Vichy’s spa experience. Of the two, my preference is for this less glitzy encounter with nature, where instead of the taste of Vichy’s Célestins, I can touch Chaudes-Aigues’ Par water. Well, I could if I didn’t mind a scalded hand – at its source, above the marketplace, the Par gushes out of the taps at 82°C. It’s the hottest in Europe; even on a scalding day, steam rises from the spring as if the ambient temperature marked sub-zero.

Crossing the Truyère for the last time, I pass through Saint-Flour, another hilltop town of Art and History, before turning west to Murat. This Petite Cité de Caractère, like Chaudes-Aigues, lines a hillside with slender town houses beneath miniature curved slates. The town, with its surrounding humps of basalt, is a gateway to the Monts du Cantal. The sun is unusually high and summery, yet the woods that line the valleys stretching towards the Pas de Peyrol (the highest mountain pass in the Massif Central) are dressed with autumn: rich orange hues prickle the treetops and rust brown cloaks lie across the mountains, including Puy Mary.

An ascent of this show-stopping Grand Site de France warrants spending time upon the summit to appreciate the vast panoramas. And I would, were it not for the squadron of flying and, more alarmingly, biting ants who are disobeying France’s ban on short-haul flights.

Taking to the skies

Heading back north, I arrive at the Auvergne’s most northerly collection of volcanoes, the Chaîne des Puys and take the panoramic train that circumnavigates the Puy de Dôme as it climbs to the summit. Paragliders circle overhead like vultures. It is not so much the volcanic chain of scalloped hills that draws my attention at the top, but the limited space on which Renaux landed his aeroplane.

To develop safe passenger aviation, Michelin, from his base in neighbouring Clermont-Ferrand, had declared that the Grand Prix could only be claimed if a pilot landed his plane on the summit of the Puy de Dôme without crashing. Renaux, masterfully, did just that.

No sooner do I leave the lava dome behind than I pick up the River Sioule and follow it downstream as it flows northeast through a wooded granite gorge to Ébreuil. At neighbouring Gannat, I catch the train to medieval Montluçon. The carriage winds its way through the Allier countryside like a meandering river, through woodlands, passing by pastures of cattle and over viaducts five of them, including the Viaduc de Neuvial and Viaduc Rouzat, which crosses the Sioule. Both are listed structures, designed, in part, by Gustave Eiffel.

I finish my tour of the Auvergne at Charroux, a hilltop Plus Beau Village north of the Sioule. Pink valerian erupts from crevices in the village’s stone walls as I approach the central bullseye Cour des Dames through the spider’s web of narrow streets. At the edge of the village, a giant sycamore tree shelters a hilltop viewpoint. Autumn fog blankets the Allier valley with the hills of the Livradois-Forez behind.

Further round the panoramic landscape, the Puy de Dôme protrudes above the skyline. Aeronauts exit the summit train with expectation; like giant beetle shells, their bulging backpacks bring up the rear. From the spot where Renaux touched down, they lift off, their airborne canopies emerging above the dome. Not an aeroplane in sight.

From France Today Magazine

Lead photo credit : Puy Mary © Caroline Mills

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in auvergne, green travel, rail travel, road trip, train travel

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *