The Lair of Le Tigre: Visiting the Musée Clemenceau in Paris

The Musée Clemenceau, in the heart of Paris, remains relatively unknown to the public, which beggars belief as it’s been there since 1931, barely two years after Georges Clemenceau’s death in the very apartment where it’s situated. Clemenceau lived at the apartment for 35 years, and from there shaped the major events of his time: the Dreyfus case, World War 1, the Armistice and the Treaty of Versailles. A French version of Winston Churchill, Clemenceau was much admired by the British statesman, who visited him whenever he came to Paris.

Everything is brought alive at the museum, by the superb audio guide (which is available in English, too), featuring the first-hand report of Lise Devinat, the great-niece of “Uncle Georges”. Proust fans will be thrilled to find out that Clemenceau took over the lease of the apartment from the celebrated poet and aristocratic dandy, Robert de Montesquiou, after whom the ludicrous Baron de Charlus in À la Recherche du Temps Perdu was largely modelled.

A Public and Private Life

Credit: Musée Clemenceau / Clemenceau’s garden, with the tree he planted to the left of shot

The museum is situated behind a courtyard on the quiet Rue Benjamin Franklin, west of the Trocadéro in the 16th arrondissement. Coming from the Trocadéro, I paid a nod of respect to Benjamin Franklin’s statue, who lived at the nearby 62 rue Raynouard. Even a century after Franklin, at the time of Clemenceau, this was still a ‘village’ with houses and gardens – which is why Georges, whose love for gardens and nature dated back to his childhood in the Vendée, moved here. The Eiffel Tower, of which I caught a glimpse on my way, wasn’t even on the agenda when Clemenceau moved here in 1895.

The visit starts upstairs, where Clemenceau’s life story unfolds chronologically, then continues in his downstairs apartment, which has been left largely as it was. Even the bathroom has been kept – its big bathtub was a luxury in those days, though not to Clemenceau, who started out as a medical doctor and was concerned about hygiene.

Public and private life are cleverly intertwined on both levels. Introducing the exhibition upstairs, for example, is Clemenceau’s cradle, brought over from the Vendée, where he was born on September 28, 1841. His deathbed is downstairs, left as it was when he passed away at 1.15am on November 24, 1929. The dining room hasn’t changed either – dinner was served there at 12.30pm, in company of friends and family, and Clemenceau followed it with a nap on a couch next to the table.

Credit: Musée Clemenceau / The dining room where Clemenceau dined daily at 12.30pm, then took a postprandial nap

When Clemenceau moved here, he’d been divorced from the American mother of his three children, Mary Plummer whose portrait hangs upstairs, for three years. Clemenceau, who was by no means a lily-white husband, had her followed for adultery, jailed briefly then expelled from France, penniless – an action very out of line with his fight for justice and social reforms or his compassion for the poor and the soldiers in the trenches.

In this dining room, Mathieu Dreyfus convinced Clemenceau of his brother Alfred’s innocence, following which he threw himself into the battle and, on January 13, 1898, covered the first page of his paper, L’Aurore, with Emile Zola’s famous manifesto, J’Accuse…!. We find out that it was he, not Zola, who came up with the audacious title.

On display upstairs are the pistols Clemenceau used for his 1892 duel against the notorious anti-Semite Paul Déroulède. He was involved in some 50 duels over the years, a common practice that plagued France until World War I. Clemenceau also fought with his pen, via such publications as Justice and Iniquité, which brought financial ruin and forced him to sell off many paintings by Corot, Courbet and Pissarro, and much of his stupendous Japanese collection. A great art lover, the museum reveals his deep friendship with Claude Monet and his persistent efforts to have the artist’s Nymphéas hung at the Orangerie. He won this battle in 1928 and the victory was accompanied by Nymphéas, a book he wrote as a farewell to his recently departed friend. Also hanging here is Clemenceau’s portrait by Manet, which he didn’t like, although he did enjoy the sessions and Édouard’s company. After his political defeat of 1920, Clemenceau retired from public life and devoted his remaining years to extensive travelling, writing and lovingly cultivating roses.

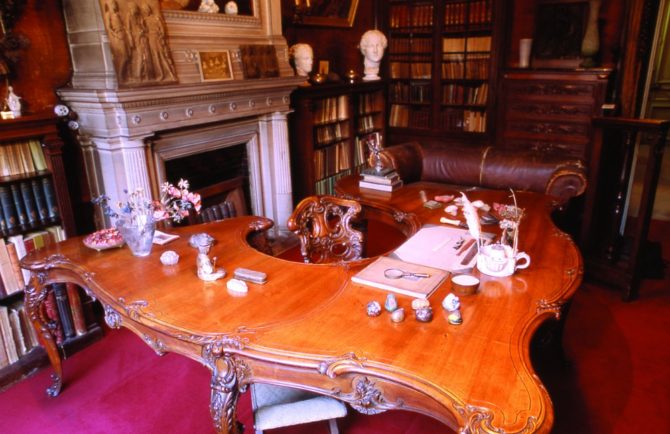

Credit: Musée Clemenceau / Clemenceau at his desk

Père La Victoire

Archive photos highlight Clemenceau’s exceptional role in World War 1. He was given full powers in the critical year of 1917, when Churchill heard him address the Chamber of Deputies “resembling a big cat prowling behind the bars of a cage, growling, roaring…” No wonder he was nicknamed ‘Le Tigre’. As the only French politician to have exposed himself to enemy artillery, soldiers called him ‘Père la Victoire’. On display are the coat, hat and gaiters Clemenceau wore walking the muddy frontline – aged 76 and ailing. After pressing the Americans to enter the war, and imposing Marshal Foch as sole commander of the Allied forces, Clemenceau’s lifelong dream came true with the recovery of Alsace-Lorraine, although he failed to press for a satisfactory treaty. On November, 11 1941, it was to the long-dead Clemenceau that General De Gaulle vowed from London to bring about victory. In 1946, vow fulfilled, De Gaulle visited Clemenceau’s grave, at Mouchamps in the Vendée.

Clemenceau’s garden is open to the public and this leafy nook still contains the tree he planted there, although his rose bushes have long gone. Enjoying this quiet oasis in the midst of the city, my thoughts went to the Canadian-born philanthropist, James Douglas Jr, who bought the house when it went up for sale in 1926, securing a roof during old age for the man he admired so much and after whom he named one of the mining towns he founded in Arizona. Together with Clemenceau’s children, he created the museum after Georges’ passing and in a display case you can see a share certificate for the Clemenceau mine and a Bank of Clemenceau cheque.

Musée Clemenceau, 8 rue Benjamin Franklin, 75116 Paris. Open Tues-Sat, 2pm-5.30pm. Closed on national holidays and during August. Tel: +33 1 45 20 53 41. Métro: Passy, Trocadéro

Thirza Vallois is the author of Around and About Paris, Romantic Paris and Aveyron, A Bridge to French Arcadia. Visit her website: www.thirzavallois.com.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *