Loire Valley Travels: Balzac at the Château de Saché

Like many travellers, the first time I visited the Musée Balzac at the Château de Saché, I stumbled upon it by chance, on a visit to the châteaux of the Loire Valley. It’s barely four miles away from the better known Azay-le-Rideau and both are situated in the valley of the Indre River. Saché is the more modest manor and was the country property of Monsieur and Madame Jean de Margonne, friends of Honoré de Balzac’s parents.

The Château de Saché was never the home of Balzac, but Jean de Margonne was the lover of his mother, Anne Charlotte Laure Sallambier, and the father of his half-brother, Henry, hence his extended hospitality to the writer between 1825 and 1848, and especially between 1831 and 1837, Honoré’s most productive years. Balzac appreciated his host’s affection but not his stinginess, and had no kind words for his “intolerant, bigoted, hunchbacked and hardly spiritual” wife, but this was a minor price to pay for shelter from his Parisian creditors, and the healthy air and peace of mind, which allowed him to focus on writing.

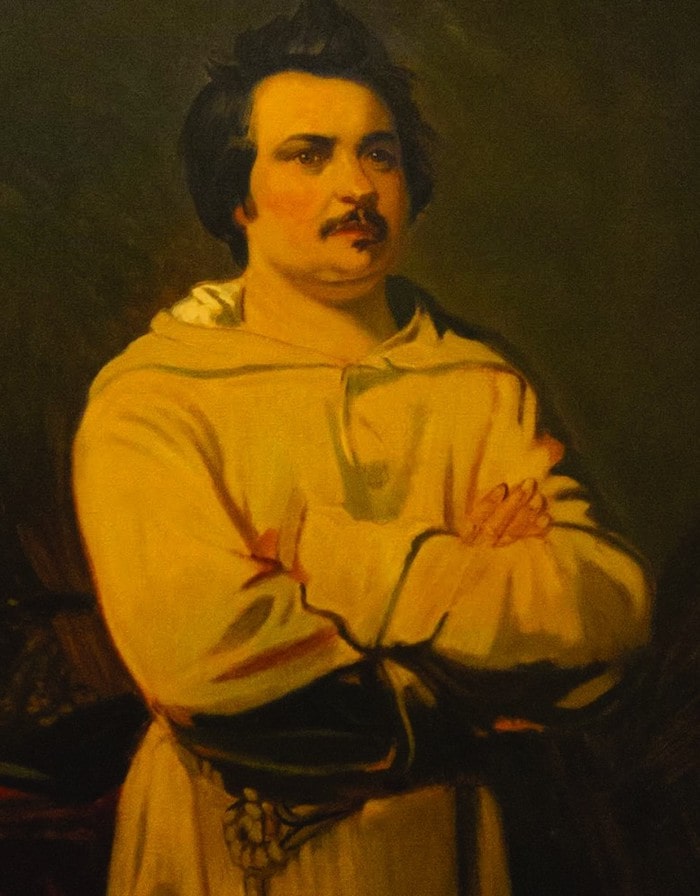

Louis Boulanger’s 1836 portrait of Balzac wearing the robe of a Dominican monk. Credit: Stuart Paterson

At the time, it was a long journey from Paris – 23 hours by stagecoach to Tours, Balzac’s birthplace and de Margonne’s main residence, and another 25 km to Saché. Honoré was obliged to walk from Tours, on the couple of occasions he wasn’t picked up, plodding along “le chemin de Charlemagne”, not unlike his alter ego, Félix de Vandenesse, in his somewhat autobiographical love story, Le Lys dans la Vallée (1835-1836), which is set in the “val d’amour” of the Indre. The prolonged walks, recommended by his doctor, Nacquart, inspired Balzac’s writing and also enabled him to discover the area.

For example, he wrote that the gem-like Azay-le-Rideau appeared as “a faceted-diamond framed by the Indre” from the top of the hill. Its real-life proprietor, the Marquis de Biencourt, was a dinner guest at Saché, and these occasions were enlivened by Balzac reading from his works. Today, fans can follow Balzac on foot through the valley, with his novel in hand.

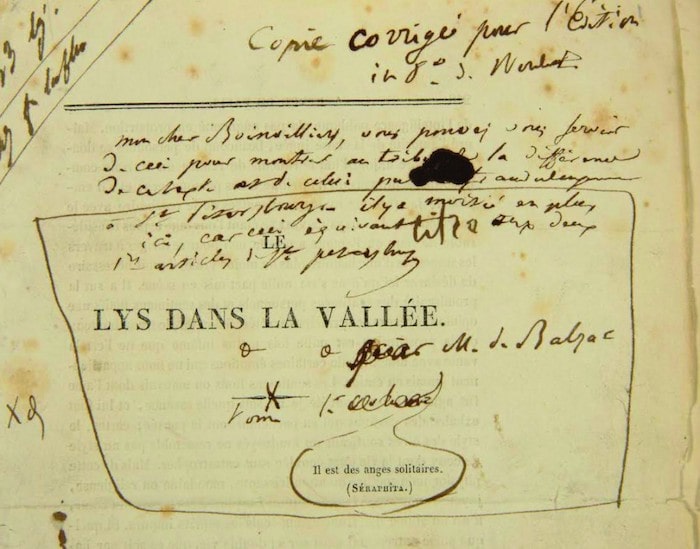

Balzac’s annotated title page for Le Lys dans la Vallée (1835). Credit: Christophe Raimbault

From Haven to Museum

Saché was refurbished by the Margonnes in the style of the time, but was wrecked and looted during the German occupation of World War 2. After the conflict, when it was recovered by its last proprietor, Paul Métadier, only the trompe-l’oeil wallpaper in the drawing room had survived.

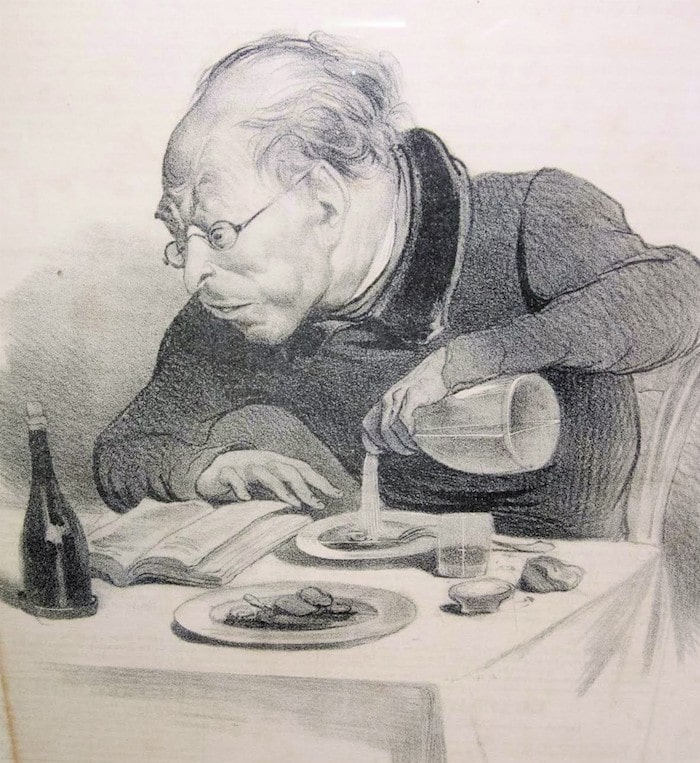

In 1951 Métadier decided to turn the place into a museum dedicated to Balzac, restoring it in spririt rather than faithfully, which was impossible due to the damage inflicted by the Germans. Now the deck of cards on the table à jouer in the drawing room brings alive those after-dinner pastimes.“This is how one kills time!” Balzac reported, partly in bad faith as he never shunned an opportunity to pocket some money and actually looked forward to playing Margonne – hopefully, to beat him at whist and “strip him of 1.5 francs at tric-trac [backgammon]”.

Balzac mocked his hosts, the Margonnes, but had no issues when winning money playing cards. Credit: Stuart Paterson

During the restoration of the dining room a fragment of the original wallpaper was uncovered and used to create the replica that now decorates the room. Its frieze inspired Balzac’s depiction of the sitting room in Maison Vauqueur, the lodging-house on the edge of the Latin Quarter in his novel Le Père Goriot (1835). Although it’s set in Paris, Balzac wrote the novel in 1834, during his stay in Saché.

As for the wallpaper in the hallway, it’s a recent addition inspired by another fragment, discovered in George Sand’s “chambre bleue” at Nohant, where Balzac visited her in 1838. Their relationship was complex, of mutual intellectual admiration but opposing political views. Balzac also mocked her feminism, teasing her as “Mon cher George” in his letters, or with snide comments: “Don’t speak to me of this writer of the neuter gender. Nature ought to have given her more breeches and less style”. Yet Sand seemed to bear him no grudges, since she wrote the preface to the Comédie Humaine in 1853, three years after his death.

The Château de Saché’s dining room, with its trompe-l’oeil wallpaper. Credit: Stuart Paterson

The Author’s Refuge

Tucked above a stone spiral staircase is Balzac’s “monastic cell”, the room most impregnated with his presence. An old photo allows visitors to ascertain that the canopy bed, armchair and dresser are the ones used by Balzac. The view of the “tranquil and solitary valley” hasn’t changed either, except that Balzac used to draw the curtains and shut it out when he worked, writing by candlelight and clad in a Dominican cowl to complete his monastic life.

Balzac’s desk. Credit: Stuart Paterson

On the desk is a coffee pot evocative of the fuel that sustained and eventually killed him, age 51, three months after his longed for marriage to the Polish countess, Madame Hanska. Picky about his coffee, he had it delivered from Paris and let it brew by his side as he worked, flat-out, from two or three in the morning to five in the evening, which is when the bell, which still hangs at the entrance to the house, called for dinner and “strangulated” his inspiration, obliging him to dress up and submit to the code of a provincial vie de château.

Samples of Balzac’s proofs reveal how he laboured over his work, making endless corrections and revisions. He was hard to satisfy, making changes to proofs even after they’d gone into print or were published, and struggled to meet deadlines, notably those for Le Lys dans la Vallée (1835) – witness his letters to Madame Hanska, ‘le doctor Nacquart’ and others.

The printing press. Credit: Stuart Paterson

The printing presses downstairs evoke Balzac’s earlier, failed attempt at the business, which led to bankruptcy. The venture fared much better in the hands of the son of his steadfast friend and mentor, Laure de Berny, his first love and 20-odd years his senior, who was the model for Madame de Mortsauf in Le Lys dans la Vallée. Much to his chagrin, Balzac wasn’t cut out for business. His genius lay elsewhere and was captured best by Auguste Rodin, who condensed his prodigious persona into one of his masterpieces, Monument to Balzac (1898), and another room is dedicated to the story of his famous statue, which created outrage in its day.

Details

Château de Saché, rue du Château, 37190 Saché

Open daily, 10am-12.30pm & 2-5pm (October 1 to March 31), 10am-6pm (April 1 to June 30 & during September), and until 7pm (June and July). Closed Tuesdays, December 25 & January 1. Tel: +33 2 47 26 86 50

Where to Eat

Auberge du XII Siècle, 1 rue du Château, Saché 37190

Situated in a 12th-century inn almost opposite the Château de Saché, this venerated culinary treasure serves local cuisine. Booking ahead is essential. Open daily for lunch and dinner. Closed Sunday evenings, Mondays and Tuesday lunchtimes. Tel: +33 2 47 26 88 77. No website.

From France Today magazine

A contemporary illustration of a reader ‘immersed in Balzac’. Credit: Stuart Paterson

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in loire valley, museums

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *