(De)tours in Tarn: Exploring Albi, Castres and More in Southwest France

Marion Sauvebois encounters art, music and religion as she discovers the many attractions – and distractions – of Tarn

“Doooo, oui doooo, encore, non rééé, miiiiii…” cue bell-ringer Jean-Pierre Carme and his glamorous assistant over the din as I sit at the baton keyboard, fist cocked, pounding away at a bungled rendition of Au Clair de la Lune. Not quite the rocking finale I had intended for the good folk of Castres on this thronged market day. Thankfully for me, after our esteemed carilloneur’s eclectic medley of God Save the Queen, We Wish You a Merry Christmas and Scotland the Brave, the whole town probably thinks he’s suffered an aneurysm anyway. The rest of our group, huddled like sardines in Notre-Dame de la Platé’s belfry, draws an obvious sigh of relief as I finally relinquish control of the chimes, pulling the plug on audience participation.

Les Maisons sur l’Agout in Castres, also known as La Petite Venise du Languedoc. Photo: CDT Tarn/ C. Riviere

We had been promised a behind-the-scenes tour of Tarn, a rare peek into the département’s hidden treasures and traditions. And I had to hand it to the tourist office: it doesn’t get more ‘behind the scenes’ than bypassing the southern nook’s star attractions – chief among them the Maisons sur l’Agout, a strip of 12th-century workshops straddling the river and now converted into social housing (!) – to hike up the bell tower of a boarded-up church and bang out a nursery rhyme on a carillon.

This predilection for unscheduled pit stops, backstage tours and detours, I am beginning to learn, is part and parcel of the méthode Tarnaise…

Castres bell-ringer Jean- Pierre Carme. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

LA MÉTHODE TARNAISE

Our first taste of the méthode comes two days before when we pull up outside Rabastens’s UNESCO-listed Notre-Dame du Bourg, for a look-see on its 700th anniversary. To our surprise, our guide casually blows right past the grand old pile, making instead for the back of the former monastery to the Town Hall, up a corridor and through the admin office.

Notre-Dame du Bourg in Rabastens. Photo: Tarn Tourist Office

“It’s behind that door,” a PA points to what appears to be a closet, a desk all but wedged in front of it, as we exchange quizzical looks. One after the other, council staff poke their heads in, the last one finally producing the key with such ceremony I am positively giddy with anticipation – a sentiment soon cut short by the pile of cinderblocks and bricks obscuring a spider web-laced stairway. Now that’s backstage, all right. Fumbling in near darkness, we grope our way up the rickety steps, emerging not only in the heart of the church but its most fiercely-guarded gem: the triforium, a shallow arched gallery wrapping above the nave, and the first ever built in the Midi region.

“We say espanté in Occitan when we mean, ‘Wow’,” our guide volunteers as we brush away cobwebs to take in the dizzying patchwork of floor-to-rib-vault frescoes, uncovered in the 19th century and all surprisingly well preserved under layers of lime render. Espanté indeed – and quite the prelude to the big event the following day: the UNESCO-listed episcopal city of Albi and its mammoth 13th-century Cathédrale Sainte-Cécile, at 78 metres the tallest brick structure in the world.

Albi’s Cathédrale Sainte- Cécile. © CDT du Tarn/ C. Riviere

Looming over the Old Town, the peach-hued ‘Fortress of God’ was erected as a hulking warning to the (by then decimated) Cathars, following the Albigensian Crusade. Funnily enough, the word Albigeois (literally the inhabitants of Albi) became shorthand for Cathars, though there is no evidence to suggest the city was a hotbed of Catharism. No matter… Not content with wiping out the pacifist sect, the vice inquisitor of France chose Albi as the seat of this brick bastion; a reminder of the might and ruthlessness of the Catholic church.

For all its austere, unadorned façade, inside this ‘crucible of faith’ (nicknames abound) is a head-spinning work of art, decked in lavish – if spine-chilling – murals; not least the 15th-century Last Judgement fresco featuring a blood-curdling cabal of demons torturing howling sinners. There is ‘comic relief’ too, though. Squint just a touch in the gloom of the ambulatory and you’ll make out little sprites darting through the marble-effect frieze.

Sainte-Cécile’s breathtaking murals. Photo: Tarn Tourist Office

Ironically perhaps, the adjoining Bishop’s Palace, the Palais de la Berbie, is now home to the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum, one of the greatest line-ups of cocottes and ne’er-do-wells ever committed to canvas – and cardboard. But before delving into this trove and the life and times of the ill-starred artist we wander down Albi’s sun-kissed streets to his birthplace, the Hôtel du Bosc.

The Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

There is to be no behind-the-scenes glimpse, or for that matter official tour, of the hôtel particulier, still a private residence and utterly off-limits, even with a tourist office rep in tow. Well, except for a cheeky peek at the courtyard as the caretaker bravely squeezes a mammoth 4×4 through the portes cochères. At least the gaping doors provide a suitable backdrop against which to share snippets of the Lautrec lore and set the record straight…

The home of his dear uncle – the man who first instilled in him a passion for drawing – this is where five-year-old Henri honed his craft, spending every naptime doodling all over the walls of his room. A period of youthful insouciance that would be cut tragically short when he broke his leg at the age of 13. Not horse riding, as decades of Chinese whispers would have us believe, but in a freak whip accident. He was mucking around by the fire, post-canter, when he caught his foot in the whip strap, fell off his chair and snapped his femur. Add to this a suspected genetic disorder characterised by brittle bones thanks to generations of inbreeding – his parents were first cousins – and his growth was stunted for good (he was 1m 52cm). A year later, he broke his other leg hiking in the Pyrénées and was crippled.

Albi’s Cathédrale Sainte- Cécile. Photo: D Vijorovic

And so, with this potted introduction, we trundle off to the museum, the world’s largest collection of works by the indomitable painter – which, incidentally, the city owes to the art world’s sheer snobbery. Determined to clinch posthumous recognition for her son following his death from complications of alcoholism and syphilis at just 36, in 1901 his mother offered his body of work to the Council of Paris Museums, and was summarily turned down by its chief, Léon Bonnat – Lautrec’s first teacher and his most vicious detractor ever since. She had no more luck in Toulouse but the good people of Albi (almost immediately) welcomed the donation. “Toulouse won’t even admit to it! They’re biting their fingers now,” chuckles Maité, our escort round the museum, mock nibbling at her nails.

A lapsed aristocrat, champion of misfits in fin-de-siècle Paris, brothel-dweller and insatiable hedonist (or downright “sex addict”, she lets slips with a guffaw after the merest of prompts), his life has been so mythologised as to overshadow his art. Yet his deft eye and knack for teasing raw beauty out of the sordid paved the way for such avant-gardistes as Picasso, while his legendary posters laid the foundation for modern advertising. Perusing the thousand-strong hoard, it’s easy to see why his racy portraits of cancan girls and assorted outcasts made Salon bigwigs hot under the collar. Not to mention his habit of painting on cardboard when he couldn’t afford canvas.

One of these cartons and the jewel in the museum’s collection was even pilfered in a Hollywood-style heist while on loan to a Japanese gallery in the 1970s. The poor guard ‘responsible’ for letting Marcelle slip away committed hara-kiri. In a bizarre twist, investigators received a letter seven years later – the statute of limitation having, conveniently, just expired – leading them straight to the looted portrait.

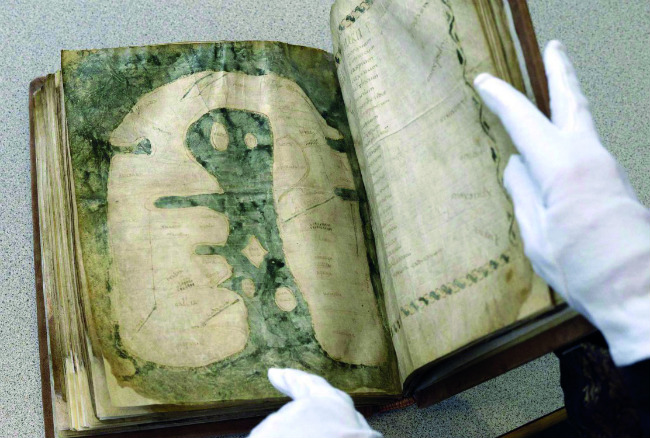

On that nugget, we are swiftly whisked away to behold another ‘recovered’ treasure: the UNESCO-listed Mappa Mundi. One of the two oldest maps in the world, it was unearthed amid the pages of an 8th-century manuscript at the cathedral. As with most ‘sights’ in Tarn, though, it doesn’t come gift-wrapped or neatly displayed behind a glass case.

The Mappa Mundi. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

After a quick stroll we arrive at the local mediathèque (library) and are ushered into a study room where a smattering of students are fiddling with their smartphones. They are quickly shooed off by a conservatrice hefting a black box – despite the mundane locale, this is an honour, and not one bestowed on just anybody. Putting on white gloves without ceremony she whips out (at a safe distance) the manuscript and reveals a strangely bloated cave doodle, which on closer inspection turns out to be an expanse of indigo sea locked in by a horseshoe of land. In two shakes of a lamb’s tail the precious book is carefully returned to its case.

THE GOD SLOT

“Fancy another detour?” asks our guide, twinkly-eyed. We all nod in unison. Which is how, five minutes later, we find ourselves at the Benedictine Abbaye d’En Calcat in Dourgne sitting through vespers, Gregorian chants rippling through the church.

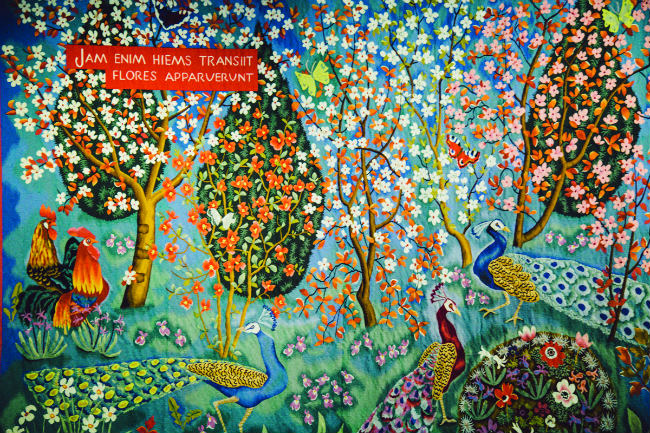

As usual, there is method (Tarnaise!) in the madness. The abbey, he clues us in later, was once home to Dom Robert, a Benedictine monk and 20th-century tapestry designer hailed as the godfather of modern tapestry but virtually unknown outside France. His vibrant motifs of rollicking fowl, coiling flora and stylised meadows not only revived but clinched UNESCO status for the Aubusson Tapestry and its workshops, where his patterns were woven.

One of Dom Robert’s masterpieces. Photo: Gregory Cassiau

You’d think the order would have been overjoyed by his success. Far from it. Considered a lapsed religieux for flouting his vow of obedience and poverty (despite donating his sideline’s lucrative proceeds to the church) he was ‘exiled’ between 1948 and 1957 to Buckfast Abbey in Devon to set his priorities straight. The plan backfired and this imposed change of scene heralded the greatest creative spurt of his ‘career’, the fruit of which is now on display at the little-known Musée Dom Robert, a stone’s throw from En Calcat, in a vast wing of the Sorèze Abbey School.

In Sorèze, an abbey and military school has been given a new lease of life as a hotel and museum. Photo: Pascale Walter/ CDT Tarn

A suitably motley repository for the multifaceted monk’s extensive work, the complex in the foothills of the Black Mountain has gone through various iterations over the centuries – first as an abbey, then an abbey/ royal military school and finally just a military school, for some 300 years until it closed in 1991. A veritable time capsule, it was recently given a new lease of life as a hotel (and museum). Though traces of its scholastic past are many: from the busts of dauntless generals scattered about and the perfectly preserved classroom and ‘show dorm’, to the registries decking the walls and bearing the names of such illustrious alumni as singer Claude Nougaro, and TV presenters (and walking billboards for the ravages of plastic surgery) the Bogdanoff brothers. Not to mention the centuries-old ‘graffiti’ and initials carved into the bare stone. Venture out into the labyrinthine grounds and you’ll spot a fenced-off pond – not a pond at all, in fact, but France’s first swimming pool, and official training ground for Louis XVI’s water-shy naval officers. Espanté, non?

From France Today magazine

France’s first swimming pool was built on the grounds of the Sorèze Abbey School. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY