Puttin’ on the Ritz: The Story Behind the Legendary Paris Hotel

It has a history as rich and famous as some of its star guests and residents, yet it has also fallen on hard times, and well within living memory.

The announcement in early 2012 that the Ritz Paris would close its gilded doors for a two-year top-to-toe renovation sent shock waves through the storied hotel’s global clientele, and all of Paris. After an additional two years of work and catastrophic setbacks, the hotel finally reopened in June, better and brighter than ever.

Bar Hemingway. Photo: Ritz Paris/ Vincent Leroux

It’s safe to say that no other hotel in the world has entered the collective consciousness quite as profoundly as the Ritz. Immortalised in song (Cole Porter wrote Ritz references while composing songs at the bar, and Irving Berlin made the Ritz a buzzword) literature and common vernacular, we know exactly what’s meant when something’s deemed ‘ritzy’.

And it’s been that way since the day César Ritz and his partner, the chef Auguste Escoffier, opened the Ritz in two 18th-century palaces on Paris’s elegant Place Vendôme in 1898. The opening was attended by royalty, business tycoons and the glitterati and literati of Paris, including 27-year-old Marcel Proust, who would write chapters of his magnum opus holed up in the hotel. By the time the Ritz Paris opened, César was already a legend, having single-handedly invented the luxury hotel by perfecting the kind of ‘sky’s the limit’ service that would catapult his far-flung lodgings – all the way from the Riviera to Johannesburg – to international acclaim.

Suite Impériale. Photo: Ritz Paris/ Vincent Leroux

For the son of a Swiss goatherd, this was no small feat. Ritz escaped the bucolic life at 15, making his way to Paris and starting his brilliant career as a bellhop. From there, he progressed, with varying degrees of aplomb, to floor waiter, maître d’hôtel and finally hotelier himself. Ritz’s adage that “the customer is never wrong” was no doubt key in his success, ingratiating him to a class of entitled sophisticates who in turn bestowed on his hotels the prestige and glamour that burnished their image around the world.

Besides a roster of firsts, like en-suite baths, electricity and telephones, what made the Ritz Paris legend so lustrous and enduring was not so much the royals and the rich, but a cast of multifarious and colourful characters – many, like César himself, from the humblest of origins – who found at the Ritz a kind of idealised home. This was the swankiest place in Paris that an urbane group of cosmopolites could hold court among themselves. A rarefied setting where, unlike real life, everything was possible.

The Lobby. Photo: Ritz Paris/ Vincent Leroux

An International Who’s Who

Making the impossible possible was one essential talent cultivated by César Ritz – and much exploited by his guests. Indulging their whims and eccentricities was another. When Cole Porter, at times an almost live-in guest, found himself in need of a grand piano by ten the next evening to perform a newly-completed score at the Paris mansion of an American millionaire, he knew just who to call. Bartender Georges Scheuer tackled the feat by hijacking a neighbour’s piano and enlisting a truck and some brawn from around dodgy Gare du Nord. And when the famous socialite and gossip columnist Elsa Maxwell showed up at the hotel at two o’clock one afternoon to order dinner for 200 at eight that night, the Ritz didn’t bat an eye. Wealthy guests brought their pet pumas, parrots and monkeys and consumed all manner of rare delicacies – including elephant, procured from the Paris zoo.

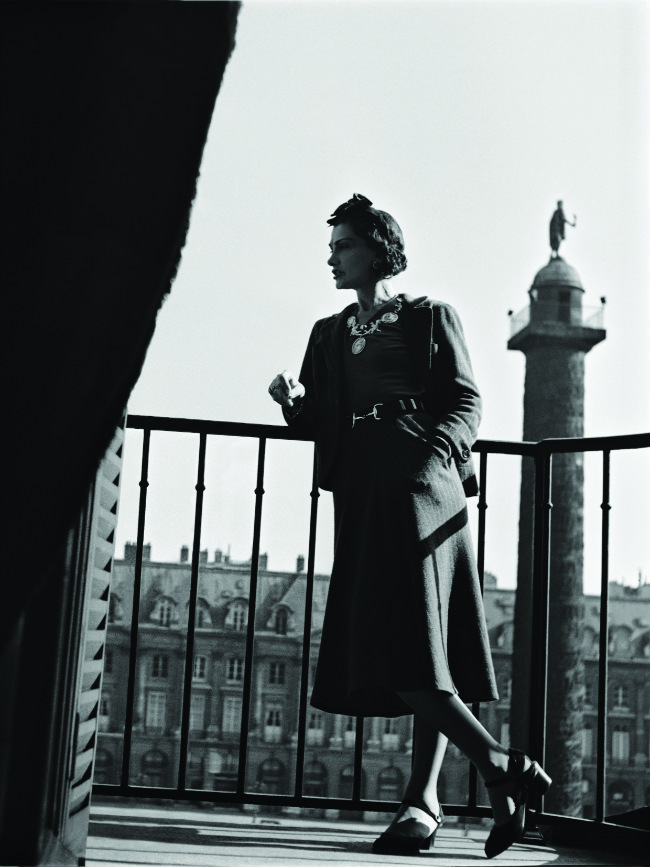

Coco Chanel at the hotel in 1937. Photo: Ritz Paris

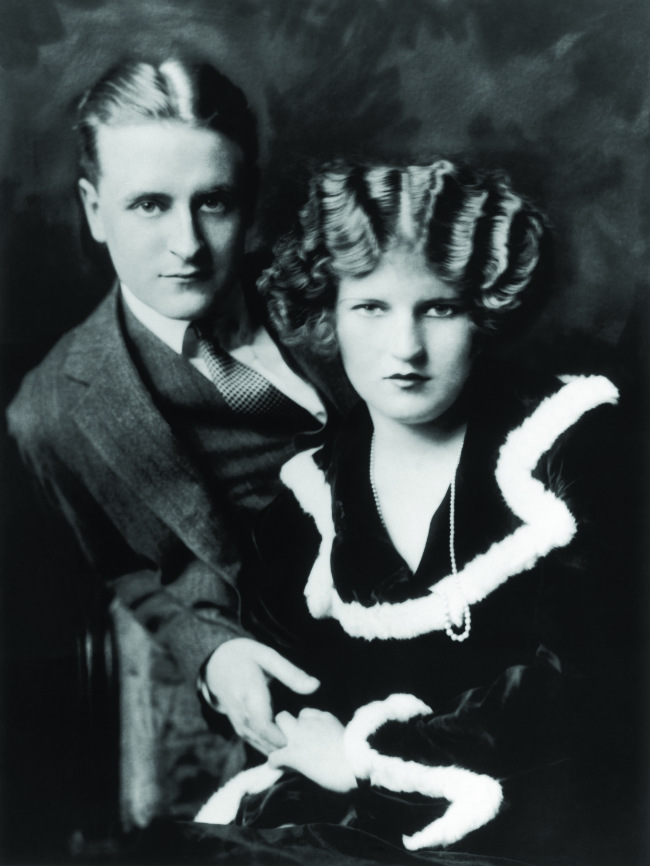

The list of famous writers who favoured the Ritz reads like a literary who’s who: Proust, George Bernard Shaw, Noël Coward, Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene, and a slew of American literary lights. Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald downed gallons of champagne at the bar, often accompanied by their friend Ernest Hemingway, then living a bohemian life in Montparnasse. But not every author shared their enthusiasm. Oscar Wilde found the in-room bathrooms intolerable and an acquaintance of the American doyenne of letters quipped that the Ritz could be divided into two groups: “Ritz and anti-Ritz. The anti-Ritz class contains only Mrs Edith Wharton.”

The Fitzgeralds

Marcel Proust

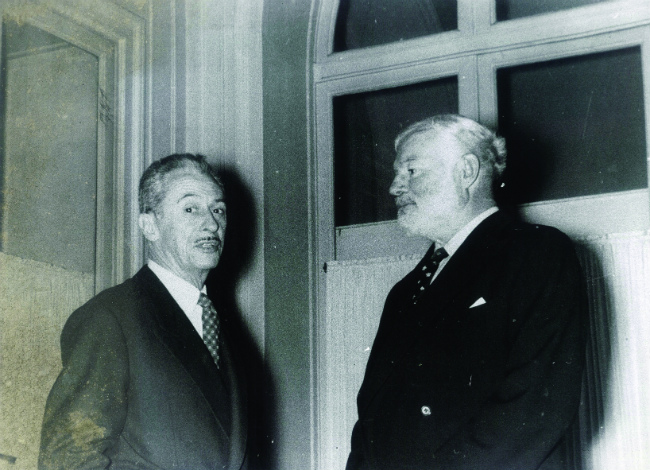

During World War II, when Paris’s grand hotels were all requisitioned by the Nazis, the Ritz was favoured by Hermann Göring, who stayed in the Imperial Suite, which he had filled with priceless stolen artworks and bowls of pilfered gemstones. As the Americans marched in to liberate Paris, Hemingway broadcast the end of the war at the Ritz – by now the author’s favourite home away from home – ordering champagne for everyone from the hotel’s newly liberated cellars and downing 51 martinis himself in celebration.

Charles Ritz with Ernest Hemingway. Photo: Ritz Paris

A Change of Hands

By the 1970s, the hotel seemed past its prime, a slightly threadbare relic of another era. But its fortunes took a turn in 1979, when the Egyptian billionaire Mohamed Al-Fayed bought the hotel for $30 million and poured another $250 million into a massive ten-year renovation, with the hotel open all the while. The Ritz once again became à la mode, especially for the international fashion set of the indulgent ’80s, who took Coco Chanel, the Ritz’s most famous long-term guest (35 years), as their inspiration.

Now open for a continuous 114 years, the Ritz was once again showing its age. It had not kept up with swiftly-changing technologies, and, by the mid-2000s had lost its sheen and its edge. “We needed to upgrade everything from the water pressure to our air-conditioning system,” said general manager Christian Boyens.

César Ritz. Photo: Ritz Paris

The Last Straw

The last straw came in 2010, when the French Ministry of Tourism established the criteria for a Palace hotel, a notch above the five-star designation, and did not include the Ritz. (It still doesn’t, but that will almost certainly change in 2017. There are now eight Palace hotels in Paris.) With stiff competition from palace hotels old and new – the elegant Shangri-La, opened in 2010, and the more contemporary Mandarin Oriental and Peninsula opened respectively in 2011 and 2013 – the Ritz was being pressured from all sides. But not only the Ritz, with its main competitors also receiving major facelifts – the Crillon, at Place de la Concorde, shuttered in 2012 for a massive five-year renovation, the much-loved Bristol was undergoing a five-year spruce-up while still open, and the Plaza Athénée had bought an adjoining building for an expansion and restoration – the Ritz had to follow suit.

The Ritz’s employees were kept on the payroll as 1,500 labourers – from plumbers and stonemasons to gilders and art restorers – got to work. Two years turned into three, then four and rumours swirled. Finally, in the summer of 2014, the Ritz announced it would start taking reservations in November for a March 2015 opening.

La Table de L’Espadon. Photo: Ritz Paris/ Vincent Leroux

Then, just after 7am on the morning of January 19, 2016, two months before the Ritz’s much-heralded opening, the fire station in Paris’s 1st arrondissement received a call that the hotel was on fire. More than 60 firefighters swarmed to the scene, where visible flames shot from the roof of the Rue Cambon building. Before the morning was over, fire had destroyed the entire roof and the wing’s upper floor, including several luxury suites, leaving significant water damage to the lower floors.

Shaken but undeterred, the Ritz management made a terse announcement that the opening date would be pushed back only a few months. The “fortunate” happenstance that the fire was limited to the Rue Cambon building meant the hotel was able to close off the damaged wing and stagger the openings.

The Ritz’s long-awaited reopening in mid-June put gossip that the hotel was woefully behind schedule to rest: nervous habitués concluded that the newly gleaming interiors were a triumph of sumptuous refinement, straying only marginally from the hotel’s original look (some 50 rooms in the damaged wing are scheduled to open in early 2017).

The hotel’s pool. Photo: Ritz Paris/ Vincent Leroux

Significant Changes

Though the Ritz’s newly lustrous finishes remain much the same, significant changes were made. Besides the addition of state-of-the-art technology – TVs hidden in mirrors, touchpad controls for lighting, heat and air conditioning – the entranceway ceilings were heightened and windows added giving the soaring space and staircase a gorgeous airiness. A retractable roof over the winter garden, part of the Bar Vendôme bistro, allows guests to enjoy breakfast, lunch or dinner on a charming terrace in any weather.

Though the beautiful pale cream interiors with pastel touches and plenty of gilding remain, the redesign reduced the number of rooms from 159 to 142, allowing for larger bathrooms (in which you’ll find the famous peach-collared towels and bathrobes César Ritz found more flattering to a woman’s complexion). The magnificent suites, named after famous guests – Maria Callas, Fitzgerald, the Windsors, Coco Chanel, Maria Callas – start at €7,000 a night and run to about €25,000, depending on the night.

The world’s first Chanel spa, in a nod to Mademoiselle, is a sumptuous affair. Done up in the designer’s signature black and cream, its bespoke treatments and products are exclusive to the Ritz. A tiny branch of the chic David Mallet hair salon is a failsafe place for a coiffure on the fly.

Salon Proust. Photo: Ritz Paris/ Vincent Leroux

For mere mortals, the gastronomic L’Espadon restaurant may be a stretch, but a trip to the exquisite new Proust tearoom (teatime menus: €55, €75 with a glass of champagne) or the Hemingway Bar for a bespoke cocktail (€24-€68) by star bartender Colin Field may suffice. The gorgeously outfitted Ritz Bar, once reserved for women only (as they waited for their spouses in the men-only bar across the way), is a jewel box in copper and black lacquer.

Many have decried this Ritz’s strict adherence to its former DNA and its seemingly counter-intuitive insistence on tradition, but they are missing the point. If you want sleek modernity in your palace hotel you needn’t look far. But if your dream is to bask in the glow of a Paris legend for a night, an afternoon, an hour, there has only ever been one Ritz, and there only ever will be.

From France Today magazine

Suite César Ritz. Photo: Ritz Paris/ Vincent Leroux

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY