Echoes of the Past: Prehistoric Wonders in Southern France

Sue Aran explores the prehistoric wonders of southern France, a region dotted with reminders of our ancestors.

I was rereading a book called A Summer in Gascony by Martin Calder and was reminded that one of the oldest ivory statuettes ever found anywhere in the world was less than a two-hour drive from my house. The Venus of Lespugue, dating from 20,000 BC to 29,000 BC, was discovered in 1922 by René Saint-Périer, in the Grotte des Rideaux, a cave in the gorge of the river Save in the Haute-Garonne. I decided to take a journey of discovery over the past year along the old Salt Road, which has linked the Atlantic to the Mediterranean since the Stone Age, and up to the Dordogne where there are innumerable prehistoric sites.

Marcel Ravidat, sitting front right, discovered the Lascaux cave paintings when his dog disappeared down a hole, to the amazement of experts around the world © Wikimedia

After a leisurely drive I veered southeast of the village of Boulogne-sur-Gesse and quickly spotted two signs indicating the village of Lespugue and the Grotte des Rideaux. Climbing high along a narrow, serpentine switchback, I reached a small parking lot across from a rusted blue sign for the ruins of the Château de Lespugue. I parked and walked through inches of thick mud from recent storms to where the château hung precariously from a cliff above the gorge. I continued on to the centre of Lespugue, but found businesses closed, including the museum. There was nothing heralding one of the greatest discoveries ever found from the Upper Paleolithic era, except a huge concrete reconstruction of the statuette, which in reality is a mere six inches tall. The gorge, too, was inaccessible.

Thoroughly disappointed, I walked back to the car, pulled out my Cadogan, and found another prehistoric site in the village of Brassempouy. The lush region of the Chalosse in the Landes département is home to the earliest known realistic representation of a woman, the Venus of Brassempouy. The village lies between the fertile valleys of the Adour and Gave de Pau rivers and its most famous resident is a strikingly beautiful mammoth ivory statuette less than two inches tall. She is also known as la Dame à la Capuche, (Lady with a Hood) because of her stylised cornrow headpiece.

The Dame de Brassempouy © Wikimedia

The very first Upper Paleolithic sites in France were just being excavated at the end of the 19th century along the foothills of the Pyrenees when the archaeologist Édouard Piette (1827-1906) arrived in 1894. He discovered the 25,000-year-old Venus of Brassempouy statuette fragment in layers of ivory found inside the Grottes du Pape. In Brassempouy, other regional archaeological objects are on view at the Maison de la Dame, a small, partially underground museum, and the dig sites themselves can be visited during the summer months.

I thought about the people who created the first art when the last traces of the European Ice Age were receding. Who were they? What was their culture like? With no written history available, I delved further into the echoes of the past.

Early one morning in September 1940, three months after France surrendered to Germany, 14-year-old Marcel Ravidat was walking in the woods near the village of Montignac, in the Dordogne département, when his dog suddenly disappeared into a hole. Marcel cautiously followed him and found the dog unharmed in a rock hollow. Before he ventured back up to safety, he saw what appeared to be a deep hole, body-width in diameter, from which cool air wafted upwards. His heart skipped a beat. He’d heard the story of a secret tunnel that led to buried treasure, and thought this might be it.

Lascaux Cave © Shutterstock

TEEN TREASURE HUNT

He returned later with his friends, Jacques Marsal, Georges Agniel and Simon Coencas, and they carefully navigated a pitch black, narrow shaft nearly 50ft deep into an enormous cave. By the pale light of their flickering oil lamp they saw what appeared to be a vast parade of brightly painted animals on the walls. Lascaux, one of archaeology’s most exciting finds, had just been discovered by four teenagers and a dog.

Word of the amazing discovery reached Abbé Breuil (1877-1961), an eminent prehistorian, who confirmed the paintings’ authenticity. The sensational news soon spread worldwide.

The Lascaux paintings, made by Cro-Magnon people, proved to be one of the most extensive and complete examples of Upper Paleolithic art in Europe. They comprise a breathtaking assortment of delicate and dramatic images, including some 6,000 representations of animals. Remarkably sophisticated, they were painted with a variety of pigments, including red hematite, yellow goethite and black manganese.

The Venus of Lespugue © Wikimedia

The nearest source of these minerals was almost 250km south of Lascaux in the middle of the Pyrenees, suggesting that the people who painted the caves either had access to trade routes throughout the south of France, or had travelled a great distance for the purpose of obtaining the vivid colours to create their artwork. The Lascaux paintings date to about 17,000 BCE and depict aurochs (now extinct wild cattle), stags, ibex, bison, felines, a bear, a bird, a rhinoceros and a multitude of horses. By one estimate, horses account for no less than 60 per cent of all the animals in the caves. There is also a figure of a man with a bird’s head, perhaps a shaman. Prehistoric cave art is important because it’s one of the best ways of understanding the interaction between our ancient ancestors and the world they inhabited. The paintings not only give us a recorded history of their complex culture, but they also document a powerful form of communication between clans and generations. Recent theories have linked some of the paintings with constellations in the sky, including the Pleiades and Taurus, or connected them with ritual dancing, which could induce trances and elicit visions.

The people of this age seem to have had a deep sense of spirituality, formally burying their dead under stone markers after laying them in the foetal position. They may also have believed in a great mother goddess, the source of all life, like the Venus of Lespugue and Brassempouy seem to suggest. Regardless, the artistry in these caves is extraordinary, a reminder of the vital role that art has played throughout human existence.

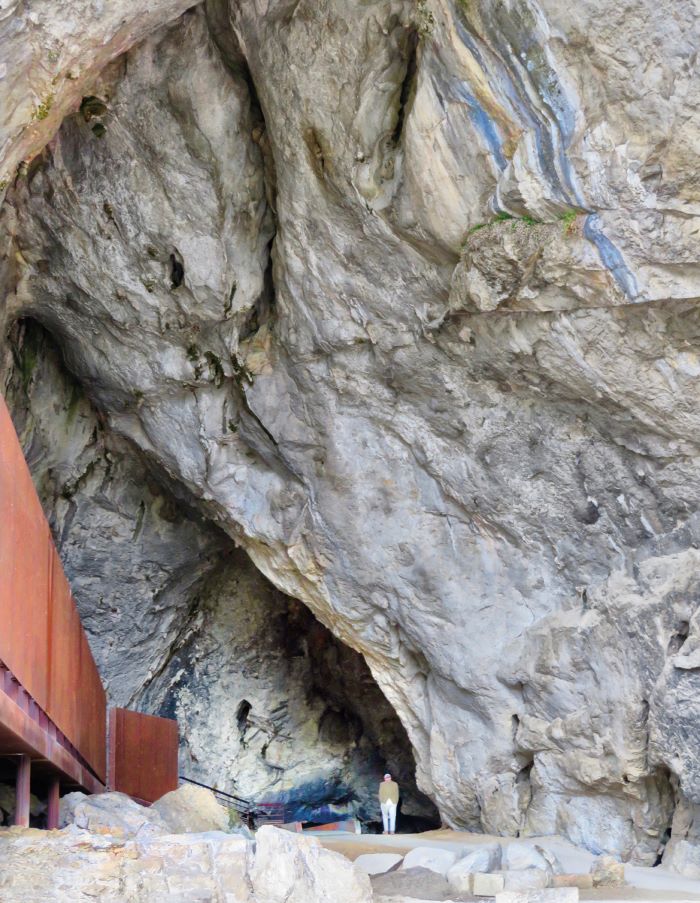

Entrance to Grotte de Niaux © Wikimedia

The roots of humanity are deep in Europe, particularly in southwestern France. We tend to think of early Cro-Magnon men and women as hairy, heavy-browed cave dwellers who communicated through crude hand gestures. But they were intelligent and capable, generating fire, inventing tools, creating their own culture, rituals and art. The Cro-Magnons’ keen eye for symbolic and abstract expression suggest they were quite possibly our intellectual equals.

The Last Glacial Period lasted from about 110,000 to 10,000 years ago. While there were no glaciers in southern France, there was open, fertile steppe-tundra on which an abundance of animals lived. As the climate changed and glaciers began to melt, many of the caves were blocked by rockfalls, which obscured and preserved them until the end of the 19th century.

In the Dordogne département of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, there lies a lush green valley spliced by the winding Dordogne River and its tributary, the Vézère. Known as the Valley of Mankind, over some 40km between the villages of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil and Montignac, the numerous prehistoric sites and decorated caves of the Vézère valley are exceptional and are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Les Eyzies-de-Tayac Sireuil is known as the Capital of Prehistory © Shutterstock

ANCESTORS UNEARTHED

This time, it wasn’t four boys and a dog who made a world-changing discovery but road workers. On March 23, 1868, they were digging near a cliff (Abri Pataud) just outside Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil when they stumbled across human skulls, alongside animal bones and tools made from flint. Louis Lartet (1840-1899), a French prehistorian, was called in to excavate what would become the oldest known burial site in all of Europe. It contained the remains of five skeletons – an old man, an elderly woman, two younger adults and a baby. These remains were the first to establish a direct link between prehistoric and modern man: Cro-Magnon people, as they became known following the discovery, belong to the same species as ours, Homo sapiens – we are their descendants.

Evolutionary geneticists believe Homo sapiens are still evolving, as are other animals and plants, but opinion is divided as to what that might mean for our ability to respond to the stresses of future pandemics and the extremes of climate change. “Climate change won’t extinguish life, by any means, there will be things that can adapt,” says scientist Michio Kaku. “But to recover the enormous biodiversity that exists on the planet now will take tens of millions of years.”

As well as a window into the lives of our earliest ancestors, prehistory shines a light on who we are now, and where we are going in the future.

Museum of Prehistory near Les Eyzies © Shutterstock

Nicknamed the Capital of Prehistory, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil is an ideal base from which to visit the prehistoric sites of southwest France. Several are within walking distance, including the National Museum of Prehistory (musee-prehistoire-eyzies.fr) where skeletons, carved figures and numerous artefacts are on display. Other prehistoric sites, including caves, caverns and museums further afield are listed below.

PREHISTORIC FRANCE: A TIME TRAVELLER’S GUIDE

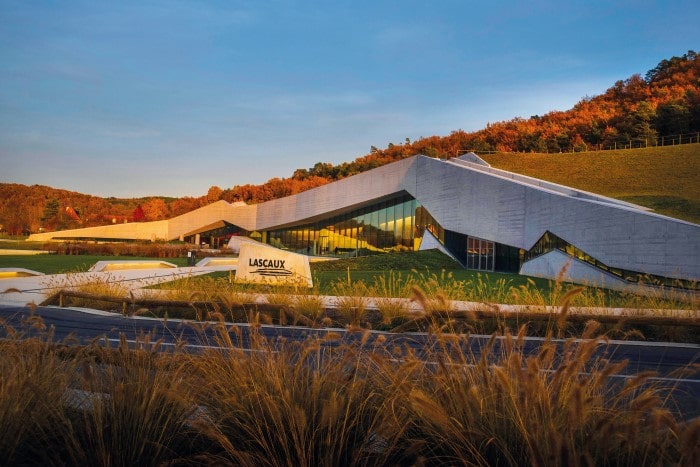

LASCAUX IV – Dordogne

Lascaux was the first cave to be closed to the public due to algae and calcite deposits caused by human breath. But don’t despair – Lascaux IV is a faithful reproduction of the original cave.

www.lascaux.fr

FONT-DE-GAUME – Dordogne

The only cave in France with multi-coloured paintings that is still open to the public. Only 78 people allowed per day and you can’t book ahead. 200 paintings of bison, horses, mammoths, a wolf and a woolly rhino.

font-de-gaume.monuments-nationaux.fr

ABRI DE CAP-BLANC – Dordogne

A rock shelter with a sculpted frieze of horses that employs the natural contours of the rock to stunning effect. A young woman was buried in front of it 14,000 years ago (she’s now in the Field Museum in Chicago).

www.sites-les-eyzies.fr

GROTTE DE ROUFFIGNAC – Dordogne

An electric train shuttles visitors past the paintings of mammoths and woolly rhinos dating from 13,000 years ago, and to the Great Ceiling, depicting images of 66 animals above a sinkhole. This site has one of the few images of a human profile hidden within its walls.

www.grottederouffignac.fr/index.php/fr

GROTTE DES COMBARELLES – Dordogne

An ornate cave with more than 600 figurative paintings, mostly engraved.

www.sites-les-eyzies.fr

ABRI CELLIER – Dordogne

Just last year, archaeologists made the breakthrough of their careers in this rock shelter, when they found 16 stone blocks featuring 38,000-year-old pointillist engravings, particularly astonishing because until then, pointillism was thought to be a 19th-century invention.

www.donsmaps.com/sousruth.html

GROTTE DE BERNIFAL – Dordogne

A private cave with more than 100 engravings an drawings from 12,000 years ago. You’ll need to call the owner on +33 674 963043 to book a visit. He only speaks French and the tour will also be in French.

www.dordogne-perigord-tourisme.fr

GROTTE DU PECH MERLE – Lot

Probably France’s most impressive cave open to the public. Advance booking only. In the large chambers there are stunning rock formations, mammoth, bison, stags, stencilled human hands, and footprints.

www.pechmerle.com

LA ROQUE SAINT-CHRISTOPHE – Dordogne

A wall of limestone, 1km long and 80m high, dug with a hundred rock shelters and aerial terraces, occupied by humans since Prehistoric times.

www.roque-st-christophe.com

MUSÉE D’AQUITAINE, BORDEAUX – Gironde

Home to 1.3 million pieces illustrating the story of the region from prehistory to today.

www.musee-aquitaine-bordeaux.fr

GROTTE DE PAIR-NON-PAIR – Gironde

One of the world’s most remarkable painted caves from the Upper Paleolithic period, with engravings, including a Megaloceros, dating back 30,000 years.

www.pair-non-pair.fr

GROTTES DE COUGNAC – Lot

These two caves have 30,000-year-old paintings of ibex, mammoths deer and humans.

www.grottesdecougnac.com

The entrance to the world-famous Lascaux caves; the Venus of Brassempouy with her distinctive ‘hood’ IMAGES © DAN COURTICE, PHGCOM

LE GOUFFRE DE PADIRAC – Lot

Take a journey deep into one of the largest chasms in Europe and enjoy a boat ride on an underground river

www.gouffre-de-padirac.com

DAME DE BRASSEMPOUY – Landes

The Maison de la Dame presents numerous objects from the cave, including animal bones, flint tools, ornaments and moulds of Paleolithic female figures.

www.prehistoire-brassempouy.fr

GROTTES DE LESPUGUE – Haute-Garonne

A series of limestone caves most famous for the dsicovery in 1922 of the Venus of Lespugue.

lieux-insolites.fr/hgaronne/lespugne/lespugne.htm

MUSEUM OF PREHISTORY, AURIGNAC – Haute-Garonne

Artefacts, maps, timelines, graphics and short films help us to understand the lives of our ancient ancestors.

www.musee-aurignacien.com/en/prehistoricshelter-aurignac

GROTTE DU MAS-D’AZIL – Ariège

An interpretation centre immerses you in the life of early man and the excavations by archaeologists before marvelling at the rich collection of prehistoric objects from the cave.

www.sites-touristiques-ariege.fr/grotte-du-mas-dazil

GROTTE DE NIAUX – Ariège

The Salon Noir is host to many stunning animal paintings along with enigmatic geometric symbols.

www.grottes-france.com/grotte-de-niaux

GROTTE DES TROIS-FRÈRES – Ariège

Numerous Magdalenian engravings of bison, horse and reindeer, plus the world-famous Sorcerer.

cavernesduvolp.com/en/grottedestroisfreres

GROTTE DE BÉDEILHAC – Ariège

The 16,000-year-old decorations include painting, engraving, clay models, plus a Cro-Magnon handprint.

www.sites-touristiques-ariege.fr/grotte-de-bedeilhac

FURTHER EAST

GROTTE DE CLAMOUSE – Hérault

www.clamouse.com

GROTTE DES DEMOISELLES – Hérault

www.demoiselles.com

GROTTE CHAUVET-PONT D’ARC – Ardèche

archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet/fr

AVEN D’ORGNAC – Ardèche

www.orgnac.com/en

From France Today Magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in activities dordogne, archaeology, cave art, museum, paleolithic caves, Paleolithic era

By Sue Aran

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY