Following the Heart: Synchronicities along the Way

A few days after the terrorist attacks at the Bataclan I was sitting in Paris outside Shakespeare and Company, lifting my plummeting sugar levels with a wholly forgettable slice of pumpkin pie bought from that iconic bookshop’s newly opened café. Its cook had not read Sophia Loren on the great subject of American pumpkin pie, notwithstanding that the icon of the Left Bank is American through and through!

The aftershock of Bataclan compelled me to go to Paris in order to pray in solidarity with Parisians, with all of France. I flew there from Bristol and found a city subdued, quiet, as people continued to go about their days just as they did before Friday the 13th November: If we do not continue as usual, said Parisians, they will have won.

Notre-Dame de Paris rose high on the other side of the Seine from where I was sitting. The queue to enter stretched an hour or more; I doubted I had the wherewithal to stand that long. I dithered about whether to go into Notre-Dame or go to the Place de la République, close to the Bataclan, to lay my gift and prayers. So soon after the terror the city was armisticed with security. The whole of Paris was armisticed with security, for the COP21 Conference on Climate Change was being held a couple of blocks away.

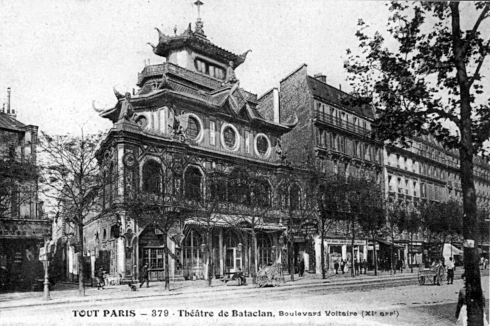

Bataclan 1900, photo: Nigelle de Visme

In time I was able to venture across the bridge and hover, uncertain, by the front end of the endless queue waiting to enter Notre-Dame. A strange magic shadowed my uncertainty; a large man approached to transect the queue. As he did so the couple he passed in front of stepped back to let him through without pausing in their conversation. In that nano-second a small black-coated invisible-old woman spun sprightly into the space he left. Conversation continued; no frisson of curiosity alarmed anyone of my interception. Three people ahead of me … and I was at the door, my bag explored, a smile, a wave, and I was through; decision made.

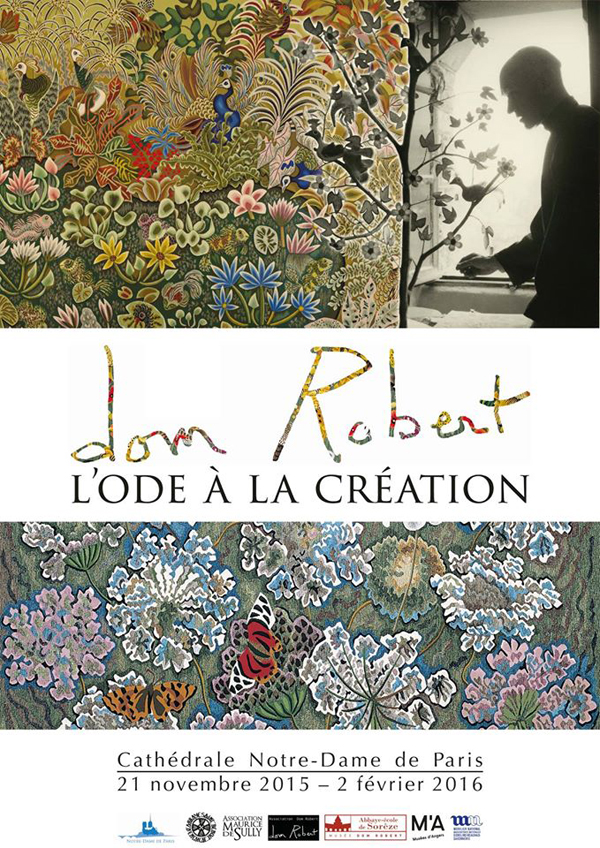

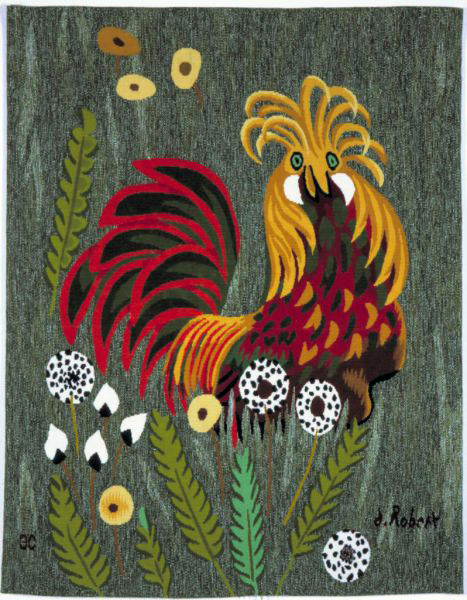

Dom Robert at Notre-Dame poster, photo by Nigelle de Visme

I moved to the right and walked down the side aisle. I did not know where to leave my book as my gift of peace, a book I had written, or where to sit and pray. I walked slowly, glanced left across the nave … and turned to molten heat. I fell out of my skin. My body became an amalgam of goosebumps. Coup de foudre. Impossible then, and now, to give words to the ineffable – time had slipped its bonds.

******

Twenty five years ago I met the late Dom Bede Griffiths and over the years a close friendship developed between us. His own story of his life as a Benedictine monk with the Benedictine community of Prinknash Abbey near Gloucester, and his invitation to travel to India to continue the dialogue centre in Tamil Nadu founded by two French religious in the 1950s, is too well known to repeat here. I knew Father Bede well for more than a decade before his death. As my off-piste guest for four days during his final Australian tour in 1992, Father Bede had asked me to continue his ‘journey with the Black Madonna’ which readers of Shirley de Boulay’s seminal biography of Bede will know as his penultimate katabasis.

My obedience to his request brought to my attention a copy of Ean Begg’s gazetteer: The Cult of the Black Virgin. Absorbing it fired my courage; I knew what I must do, make a pilgrimage to all the shrines in France mentioned in that book. I began to plan. Slowly ideas took form, though the dream took a couple of years to realize.

Eventually action was demanded and I wrote to every airline in Australia asking each if they had a spare seat in the back of their planes where I might sit: as quietly as a nun, all the way to Paris and back, to do my research on the Black Madonna. I think I wrote 27 letters to every airline flying out of Australia; in those pre-computer days each was written by hand. I only needed one ‘yes’. I received eight replies; six were ‘regretfully, no’; Air France said yes but they no longer flew out of Australia – could I get to Singapore? And one wrote Yes, addressing me as Sister in response to my ‘nun’. When would I like to go?

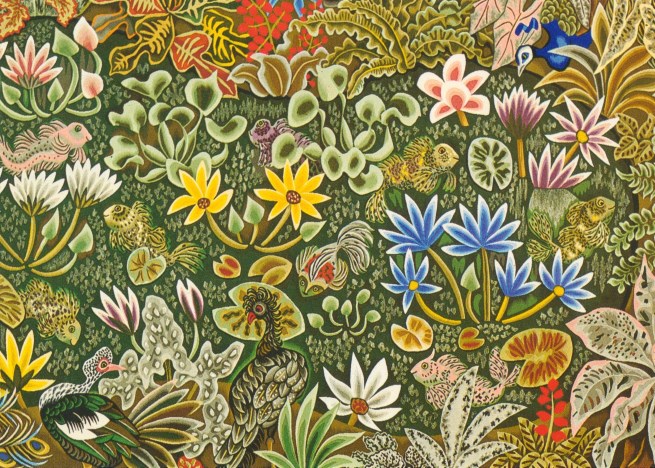

Dom Robert Les Enfants de Lumiére, photo by Nigelle de Visme

Their offer was open ended, asking nothing in return, no article, no commitment. It was Malaysian Airlines. I had been partially brought up in Malaya; I like to imagine their generous offer was in the spirit of interfaith dialogue – but I couldn’t be sure.

A friend came along to share the open-ended journey. She had recently sold her house and considered a treat was in order. We landed in Paris, picked up our leased Renault, and headed for Dijon and our first remarkable Black Virgin, and I fell deeply and irrevocably in love with France.

On our second day, having been awed by the presence and living prayer of everyone in the chapel of the Black Virgin of Dijon, a Madonna of hieratic calm, we drove on quietly through the great forests of Morvan to our first monastery: l’Abbaye Sainte-Marie-de-la-Pierre-qui-Vire. Women guests each had a cottage of their own in a small medieval village on the hillside; men would stay within the monastery itself. The village had been abandoned, the Abbaye bought it, the monks restored it. Everything about each cottage was charming; their beauty inclined one to remain forever in the magical world of serenity created by the monks. My first experience of a living western Benedictine tradition enchanted me, its impact would drip-feed my soul for years. It was the beginning of a serpentine path that would deepen and direct my own world, slowly, indelibly. My travelling companion returned to Australia after a month and I continued on tout seule. I stayed in convents and monasteries throughout my two-month journey and was privileged to find, or be guided to, or discover for myself, dozens and dozens of Black Virgins, many in tiny churches in hamlets barely marked on any map. It was a time of enchantment for me and each discovery shifted me to a broader way of perceiving. I recognised in the ‘little tradition’ of the Black Virgin a past I belonged to: a medieval past. I felt I had sprung from the 13th century, felt an ease and resonance unlike my discomfort with the modern world I was born into.

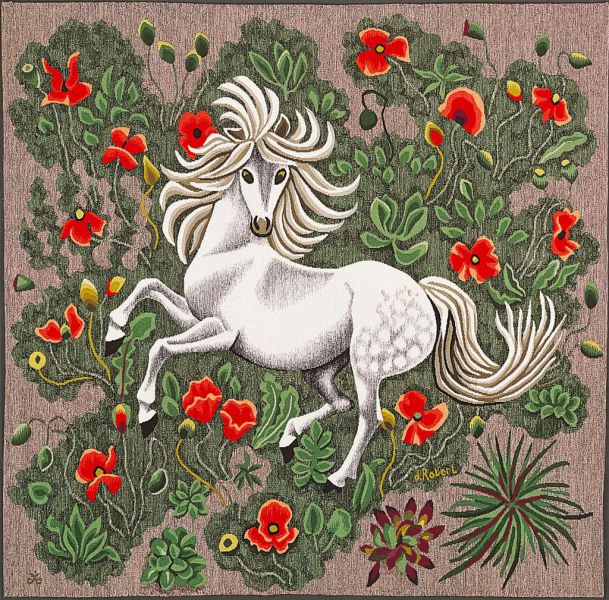

Farfardet 1981, photo by Nigelle de Visme

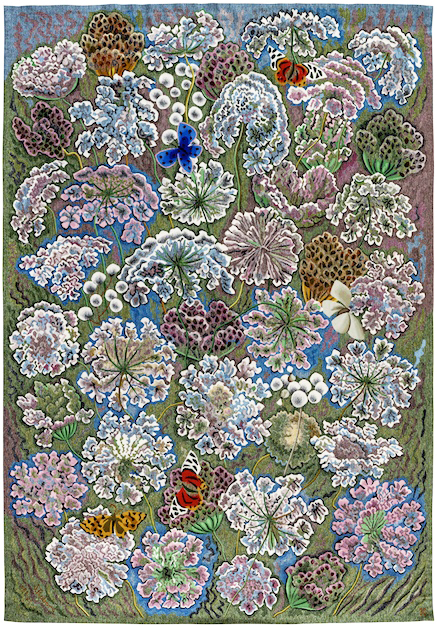

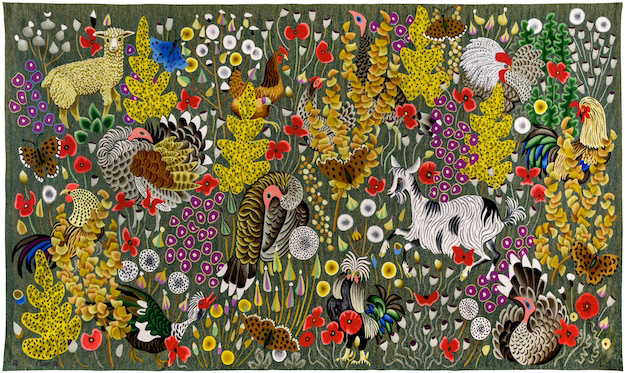

Many of the religious houses had shops selling liturgical items, herbal products, small artworks and religious carvings. I found postcards depicting an enchanted world – bright fields and prancing ponies, poppies and butterflies, wildflowers of wondrous colours. On the reverse of each was written: tapisserie, Dom Robert, En Calcat. I bought some, kept them as treasured souvenirs and have them to this day. Now, more than 20 years later, all along the central nave of Notre-Dame de Paris, were my ‘postcards’: the original vast tapestries of those very postcards which had inspired me. It was a holy moment.

*****

L’Ode à la Création was coordinated to coincide with the 2015 Conference on Climate Change, COP21, in Paris. I knew that if even one of the delegates had seen those tapestries the need for yet another costly conference of talking heads may have been averted. Only one delegate needed to be inspired with an inner fire of utter conviction; the conviction that to save our beautiful world and the last 2,000 tigers was a fire to die for; or, if not to die for, then at least to court political death and fight with courage in the face of the corporate greed that is destroying our planet piecemeal. But, alas, it’s no vote catcher, that.

photo by Nigelle de Visme

The world of Dom Robert’s tapestries sang with his epiphany. Down there amongst the wild fields and farmlands of the valleys of the Montagnes Noires of Tarn, Nature had revealed to this remarkable Benedictine monk over his long and creative life a great truth: Nature is the true Reality. Nature never deceives. Nature is the Face of God. Those were his words. They pierced my heart.

I found a pew and sat down; my whole vision filled with Laudes, Plein Champs, Les Enfants de Lumière. Thoughts spun at dizzying speed, I couldn’t have stood if I’d tried to just then because this was my epiphany too. As a child, unloved and unwanted, I knew God was the horse chestnut tree whose vast branches held me, the black cat who loved me, the dandelions holding their sunny faces as I smiled at them in return, the wind that blew birdsong to me. And here was a Benedictine monk telling this to the whole world.

Laudes, photo by Nigelle de Visme

I returned to Somerset singing and within days was sitting in the parlour at Prinknash Abbey sharing my own joyful epiphany with the Abbot, Father Francis. Why don’t you visit our sister monastery, he smiled, in the South of France, where Dom Robert was a monk?

And so I did.

photo by Nigelle de Visme

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY