Parisian Walkways: Galerie Véro-Dodat, An Historic Covered Passage

The passage couvert, these glass-roofed shopping arcades which flourished in early 19th-century Paris, owed their success in part to a promise inherent in their architecture – the capacity to transport their visitors to another place. In the 1800s, a passage couvert offered Parisians the chance to step away from the mud and hazards of a city without sidewalks into a realm both spotless and safe. It was an opportunity to escape the rain for somewhere warm and dry; to walk out of the darkness of night, and enter the sublime luminescence of gas lights. It was to leave behind the old for the modern, the unsightly for the beautiful, the quotidian for the luxurious. And of all the covered passages in Paris, perhaps none has embodied this promise like Galerie Véro-Dodat.

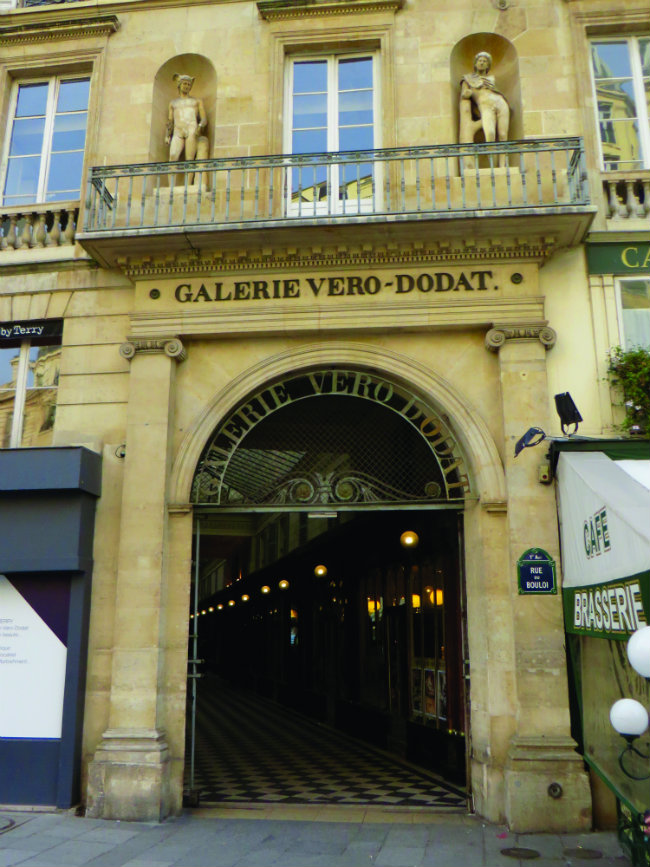

Built in 1826 between 19 rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau and 2 rue Bouloi, steps from Palais-Royal and the Louvre, Galerie Véro-Dodat is neither the longest, nor the tallest, nor the most resplendent Paris passageway, yet it is somehow one of the most affecting. It may be the uncommon harmony of its neoclassical décor – boutiques with mahogany façades and arched windows framed in gilded copper, each separated by a pair of marble columns and mirrors, topped by a globed lamp and a sculpture of a winged cherub surrounded by horns of plenty. The ceiling alternates between glass panels and ravishing frescoes of gods and men at play.

The entrance to Galerie Véro-Dodat on Rue du Bouloi. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Below, black and white diamond-shaped marble paving creates the illusion of a passage to infinity. The 1830 traveller’s guide Le Nouveau Conducteur de l’Étranger à Paris praised the “elegance and convenience” of all the new passages couverts, but reserved its most poetic lines for “Véro-Dodat, with its shimmering marble and gilding”… “To traverse it at night when it is illuminated, the flickering lights multiplying in the mirrors on the walls, is to find ourselves transported to an enchanted world.”

A close-up of Véro-Dodat’s neoclassical

décor. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Over the years, even as covered passages have gone out of fashion, Galerie Véro-Dodat has retained its transporting power. In the 1920s, artists like the writer Colette fell under the charm of the place, its ornamentation and watery calm evoking for her a marvellous “air of Venice”. Now, nearly two centuries after its construction, the forgotten, antiquated aura of Galerie Véro-Dodat seems to be working to its benefit.

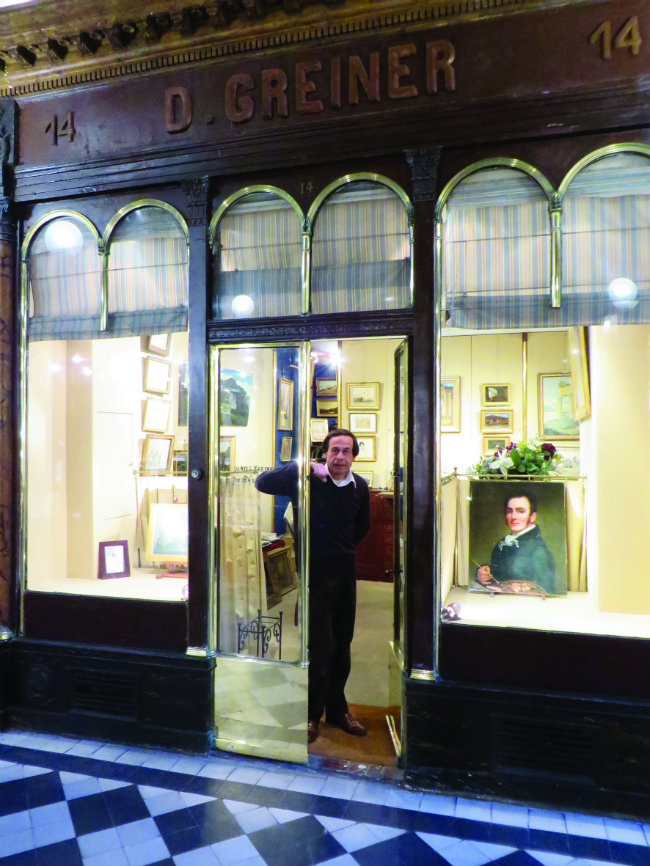

Today, the passageway is filled with boutiques dedicated to exclusive niches of various arts and trades – unique galleries, an antiquarian bookstore, a renowned luthier, luxurious artisan clothing, shoe and jewellery stores, atmospheric eateries… Apparently what all these owners desired was a locale as singular as their expertise – like that of Denis Greiner, expert in 17th- to 19th-century architectural drawings. “It wasn’t by chance that I chose to open my gallery here,” says Greiner. “No automobiles, just people passing by on foot. It’s a place that fundamentally remains a creation of the 19th century. It’s a place at once in the very centre of Paris, and completely of another world.”

Galerie Denis Greiner. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

When Galerie Véro-Dodat was created in 1826, it was immediately adopted by Parisians as the shortest route between two distinct and vibrant neighbourhoods – Les Halles, the capital’s bustling central food market, and Palais-Royal, then the epicentre of Parisian public life. Quite appropriately then, the investors behind this real estate venture were in fact two wealthy Parisian pork butchers, Monsieur Véro and Monsieur Dodat, who had broken their way into high society. A common joke of the era compared the Galerie Véro-Dodat to “Un beau morceau de l’art pris entre deux quartiers” – a play on words which literally means, “A lovely piece of art placed between two neighbourhoods,” but which sounds like, “A lovely side of bacon taken between two racks of pork”.

The arcade’s situation was certainly ideal. In the 1780s, the Duke of Orléans transformed the buildings and the gardens of the Palais-Royal into a shopping and entertainment complex open to the public, with around 150 boutiques, cafés, bookshops, gambling parlours, theatres and restaurants (including Le Grand Véfour, opened in 1784 where it still stands today). Frequented by the aristocracy but also every other class of Parisian, nowhere else in the capital could such sophisticated conversation and revolutionary debates be had, such luxurious goods, curiosities and pleasures be found. Véro-Dodat benefited from its proximity to this spectacle until the late 1830s when the complex was finally dismantled.

The elegant gas lamps remain, but are now

powered by electricity. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Palais-Royal lived on, though, as the inspiration for all the covered shopping arcades of the 19th century, not just as a real estate model but as a social model, for the considerable freedoms experienced there. At no. 38 Galerie Véro-Dodat, the famous print-seller Aubert published the Charivari and La Caricature, which emerged in the 1830s as the most famous satirical revue of the Romantic period, gathering enormous crowds whenever another scandalous caricature of a political or society figure was hung in the windows.

Besides freedom of expression, social freedoms and libertine lifestyles flourished in passageways as well. From 1838 to 1842, the actress Rachel Félix lived in one of Galerie Véro-Dodat’s third floor apartments, where she met with lovers such as the playwright Alfred de Musset. (Mademoiselle Rachel, as she was known, became the first international stage star, while remaining a famous libertine, even taking Napoleon III for her paramour.) Galerie Véro-Dodat drew pleasure seekers of all kinds, including gastronomes who came to “chez la mère Bontoux” at no. 30 for her famous timbales, a small hors d’oeuvre of meats and pasta baked in a mould, de rigueur at any fashionable mid-19th-century soirée.

Restaurant Véro-Dodat. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Today, Galerie Véro-Dodat’s décor still teems with cornucopias, the mythical horn which could provide one’s every desire. And though the umbrella makers and corset shops are gone, the arcade’s boutique offering remains nearly as diverse as it was in the 1830s – despite the fact that its days as a busy pedestrian thoroughfare are long gone. Over time, the arcade has become a confidential address indeed, hidden away between side streets, easily overlooked.

Though the most central historic shopping arcade in Paris, it’s also perhaps the least widely known. That may be why certain kinds of businesses have come to thrive in the passageway – those that are so unique, so specialised, that they don’t need to attract passersby. They draw a passionate clientele from all across Paris and beyond, so high is the quality of their vendibles, so unique is their chosen niche.

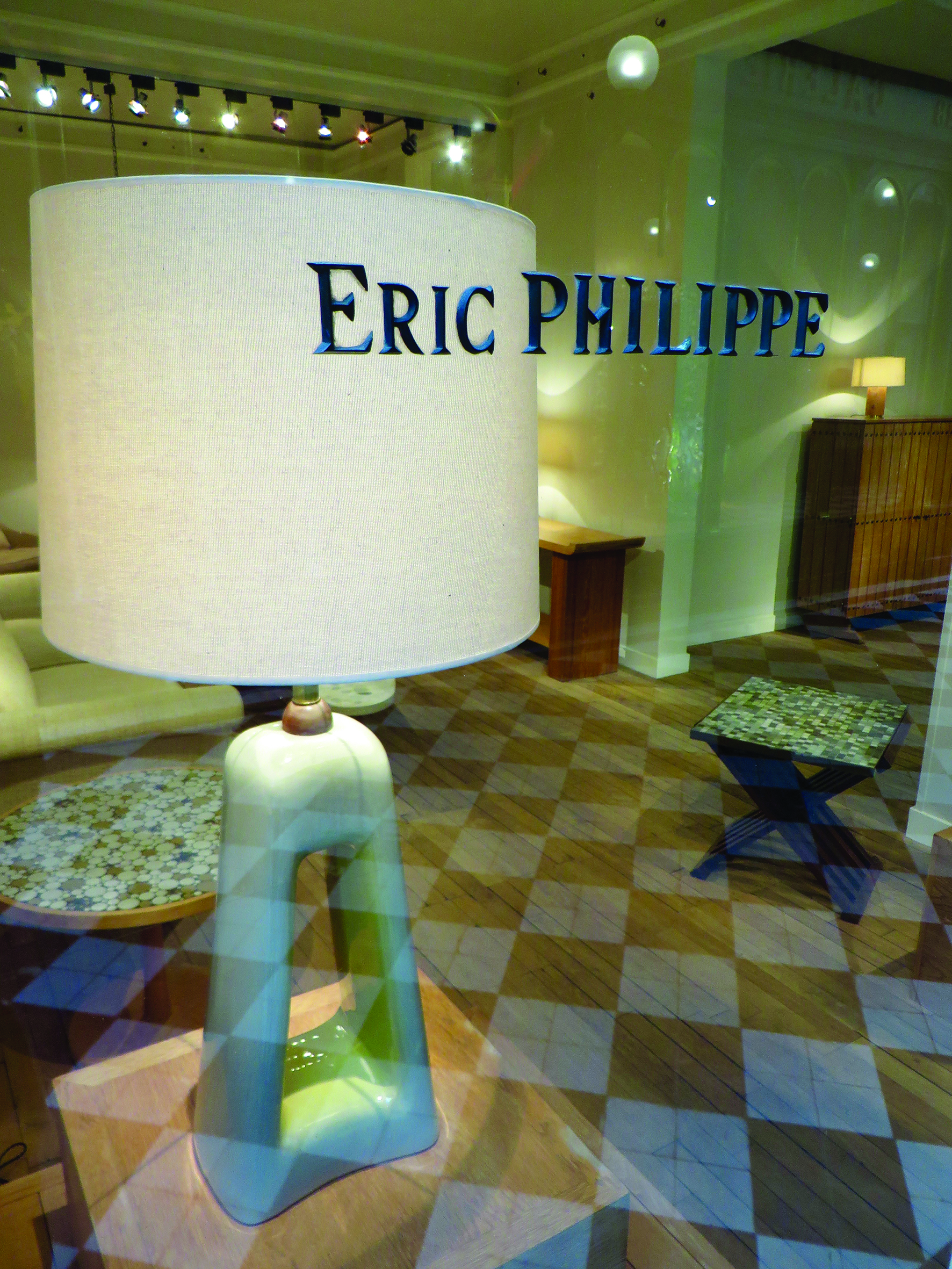

Galerie Eric Philippe

specialises in 20th-century furniture. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Galerie Véro-Dodat has become the passageway of experts. Some, like Eric Philippe and Denis Greiner, are literally certified members of France’s Chambre Nationale des Experts, called on by museums and auction houses to identify and evaluate works related to their field of expertise. Galerie Eric Philippe (no. 25) specialises in early 20th-century decorative arts and design from Scandinavia, France, America and Austria. Galerie Denis Greiner (no. 14) focuses on 17th- to 19th-century architectural drawings and paintings, proving his niche abounds with works of surprising beauty, much like Antiques Thierry Burel (no. 12) does for 18th- and 19th-century sculpture and furniture.

Librairie Bernard Gaugain. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

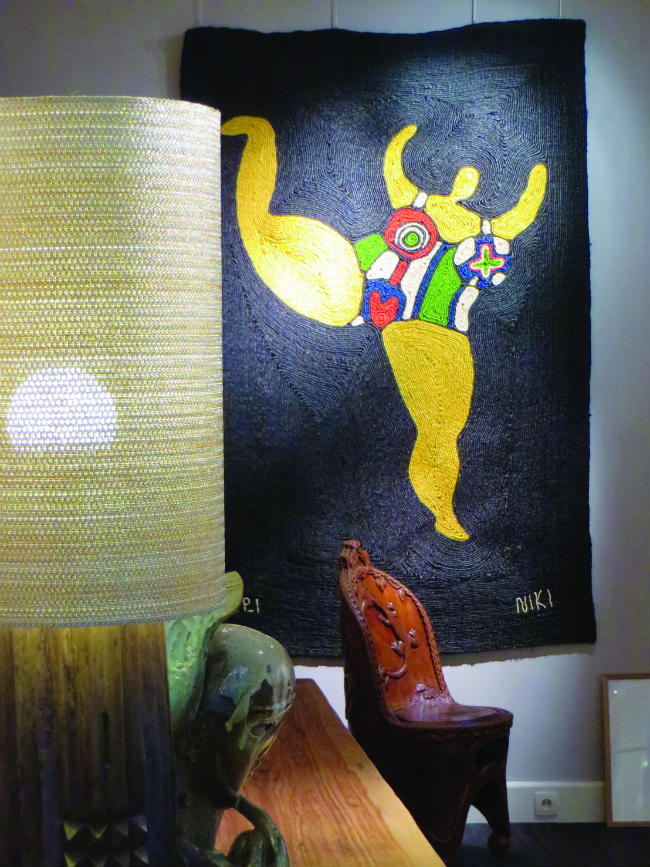

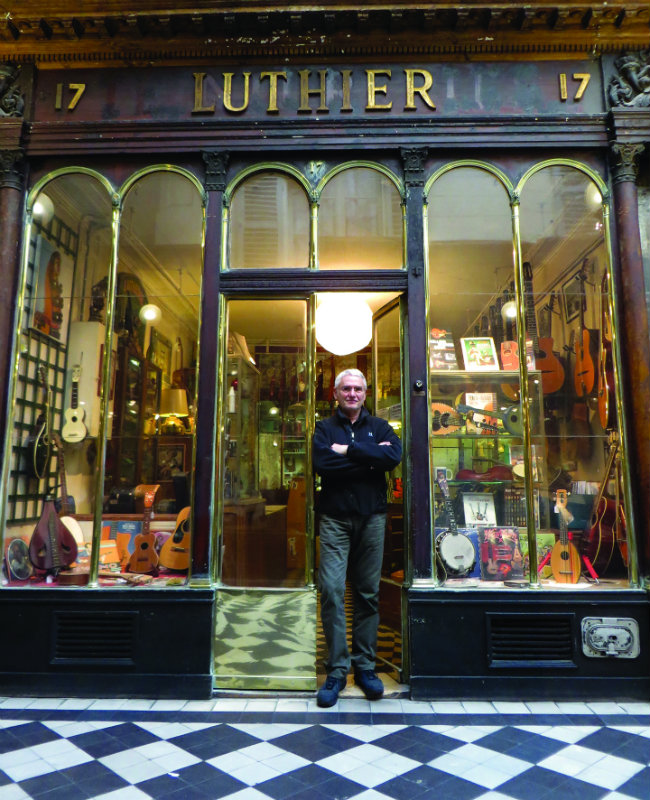

In other arts, François Charle, owner of the stringed instrument repair and sales shop F. Charle (no. 17), is a pre-eminent authority on the Selmer Maccaferri, the unique guitar used by Django Reinhardt, which has seen a revival thanks the renewed popularity of so-called ‘gypsy jazz’. And Bernard Gaugain of Librairie Bernard Gaugain (no. 13), who as a young man moved in the same circles as pop artists Allen Jones and David Hockney, and surrealists like Leonor Fini and Max Ernst, has packed his tiny shop with rare artist monographies and antique engravings. Then there’s Galerie du Passage (no. 20-26), a reflection of the stunning eclecticism of the renowned tastemaker Pierre Passebon and his sister Nathalie. A single room of the gallery recently included a 1970s wall hanging by Niki de Saint Phalle, an early 1900s Swedish Art Nouveau wooden chair, a 2016 mirror-polished aluminium table, and an 18th-century plaster Christ.

A wall hanging by the famous painter/ sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle at Galerie du Passage. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

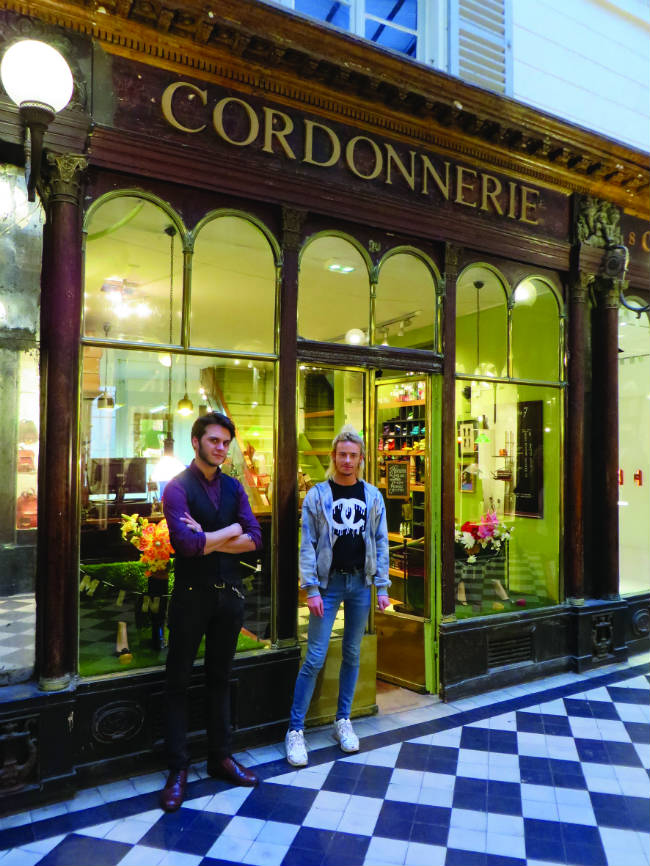

Most recently, small luxury brands like Il Bisonte leather goods (no. 11) and Angela Caputi jewellery (no. 15) have opened shops in the passageway. And in partnership with the arcade’s most famous occupant, the flagship store of star shoe designer Christian Louboutin (19 rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau), the luxury shoe cobbler Minuit Moins 7 opened a few years ago at no. 10, drawing hordes of shoe fanatics with broken heels and bruised soles. For Nathalie Passebon, such arrivals are indicative of how the arcade is evolving today. “There is a tendency for passageways to remain a bit nostalgic and turned toward the past, and for a long time there were boutiques which didn’t have much activity,” she says. “But bit by bit new businesses have made the passage more dynamic. Louboutin gave us a little touch of glamour, and By Terry [luxury cosmetics and perfume shop (no. 36)] too, while the real institutions, like the luthier and our restaurant, have endured for years.”

Minuit Moins 7, the famous cobbler. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Yes, culinary pleasures are still abundant in Galerie Véro-Dodat. The elegant Café de l’Epoque (2 Rue du Bouloi) is a guardian of authentic brasserie recipes, like their fondant de boeuf, slow cooked for hours, and their oeuf mayonnaise, ranked among the best in Paris. The soul of the passage resides in intimate Restaurant Véro-Dodat (no.19), where Gilles and Danila Gomond have been serving hearty, homemade fare for 27 years. Gilles still remembers how the arcade charmed him from his very first visit: “It’s a place that resembles nowhere else in Paris. You can pass by the Galerie and not really notice it, but once you step inside, you feel like you’ve discovered a secret, a little niche,” he says. “The only thing I regret is that it’s so intimate, so secret, that not enough people know about it.” But perhaps that’s finally starting to change.

The Café de l’Epoque sits at the galerie’s entrance. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

BOUTIQUES AND RESTAURANTS

Librairie Bernard Gaugain: 13 Galerie Véro-Dodat, Tel. +33 1 45 08 96 89

A bookstore out of another era, too minuscule for casual browsing, this is the treasure hoard of 83-year-old Bernard Gaugain, who specialises in art books and artist monographs. His clientele includes celebrated New Yorker cover artist Pierre Le-Tan, who comes for Gaugain’s rare, exquisitely bound books of illuminations and engravings.

R & F Charle: 17 Galerie Véro-Dodat, Tel. +33 1 40 20 96 74

For 35 years, string musicians have come to this charming shop to repair their old instruments and buy new ones. Stars like folk legend Steve Earle, songwriter Francis Cabrel or the swinging Stéphane Sanseverino all come to find a one-of-a-kind 1960 Martin or Gibson, a Django Reinhardt-style Selmer Maccaferri guitar, or perhaps a banjo, Dobro or ukulele.

R & F Charle in Galerie Véro-Dodat. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Restaurant Véro-Dodat: 19 Galerie Véro-Dodat, Tel. +33 1 45 08 92 06

One of the most intimate, original tables between Palais-Royal and Les Halles is also one of the most reasonably priced. For more than 25 years, Gilles and Danila Gomond have run this petite restaurant where in-the-know clientele come to dine on simple, richly flavoured, made-from-scratch cuisine amidst 19th-century splendour.

Galerie Véro-Dodat in Paris. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Minuit Moins 7: 10 Galerie Véro-Dodat, Tel. +33 1 42 21 15 47

Since this cobbler opened in 2009, Minuit Moins 7 has rapidly gained a reputation as one of the premier luxury shoe repair workshops in Paris. Thanks to a partnership with their passageway neighbour, the iconic shoe designer Christian Louboutin, they are now the only establishment authorised to repair Louboutin’s red leather soles, replace a delicate heel or a missing spike.

Galerie Daniel Greiner: 14 Galerie Véro-Dodat, Tel. +33 1 42 33 43 30

This small gallery is a model of elegance and order, fitting for a man whose expertise is 17th-to-19th-century architectural drawings. Such a niche might seem too narrow to interest your average art lover, but Daniel Greiner’s talent is unveiling the intriguing stories behind each work, be it a mysterious drawing of a Roman countess or an entrancing gouache of Pompeii ruins.

Galerie du Passage: 20-26 Galerie Véro-Dodat, Tel. +33 1 42 36 01 13

Pierre Passebon opened this spectacular, eclectic gallery in 1991 with his sister Nathalie, starting at no. 20 of the passageway. As Pierre’s career as a tastemaker has exploded internationally, so has the gallery expanded. With rare 20th-century furnishings and artworks by the likes of Niki de Saint Phalle and Alexander Calder, their clientele includes heiresses, movie stars and fashion icons.

From France Today magazine

Galerie du Passage. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *