Picasso’s Women

Hazel Smith flicks through the artist’s little black book to reveal the wives and mistresses who inspired some of the most famous paintings of the 20th century.

Pablo Picasso’s life reads like a French bedroom farce of hidden lovers, secret children and irate wives. The prolific artist had an equally prolific desire for women – whoever was in Picasso’s bed influenced his art and aesthetic. Some in his orbit were talented, independent women; others strained under the gravity of the artist’s narcissism. The saying goes, ‘behind every great man is a great woman’ and behind Picasso there were several. Here’s a roll call of Picasso’s muses.

Fernande Olivier 1904-1912

After fleeing from her bully of a husband, Fernande Olivier moved into Le Bateau-Lavoir, the boat-like apartment house on the hill of Montmartre, where Picasso had his studio. A besotted Picasso was drawn to Fernande’s refined style and chic clothes; Fernande, meanwhile, was charmed by Picasso’s unwavering, fiery gaze – and after a three-day opium-induced fog, she was in love. Both were just 23 years old, and Fernande went on to be Picasso’s first long-lasting affair. The muse who influenced his Rose Period and early Cubist works, she was the inspiration behind more than 60 paintings, including the controversial Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), and Picasso’s first Cubist sculpture, Head of a Woman (1909).

Fernande’s relationship with Picasso was tempestuous, to say the least. She said: “To keep a lover, you have to keep him jealous.” But Picasso was too possessive: violent squabbles erupted when Fernande posed for other artists, and the couple stopped frequenting cafés lest she exchange glances with another. Her affair with the Italian artist Ubaldo Oppi irreparably fractured their relationship in 1912. An avid diarist, Fernande was approached in 1931 by the journal Mercure de France to publish her memoirs of her time with Picasso. After three instalments, Picasso offered Fernande a hefty pension in exchange for her silence.

Pablo Picasso’s ‘Ma Jolie Paris’, winter 1911-12. Credit: MoMa

Eva Gouel 1912-1915

Fernande’s betrayal led to Picasso falling for her friend, the small, doll-like Eva Gouel. During his Cubist collage period, Eva was an immense source of inspiration for Picasso. He painted several series of compositions based on her, including Woman with a Guitar, aka Ma Jolie (1912), the sobriquet he gave his pretty lover.

The couple spent the first months of World War I in the south of France, escaping Paris to avoid visits from Fernande whom they rightly worried would try to rekindle a relationship with Picasso. In Paris they stayed close to home because Picasso, as a neutral Spaniard, was often interrogated in local cafés as to why he wasn’t at the Front. In 1915, Eva’s health failed. She had developed either tuberculosis or cancer of the throat. Despite his enduring support during her illness, Picasso wasn’t faithful to her. Even so, when she died, he was in despair, writing in a letter to Gertrude Stein that “my life is hell”.

Olga Khokhlova 1918-1934

A member of Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Olga Khokhlova became Picasso’s first wife. Perceived as noble, Olga was a dignified young woman with an embellished family history. She was impressive enough for star dancer Nijinsky to single her out of the corps de ballet, but her own dance troupe were less enthralled, saying that she was pretty but talentless. In 1917, Olga danced in Parade, a ballet produced by Diaghilev, Erik Satie and Jean Cocteau. Picasso created the sets and costumes. Olga’s beauty and rumours of her elevated social status impressed him and at 36, he felt it was time to settle down and produce an heir. Adamantly chaste, Olga wed Picasso in a Russian Orthodox service in 1918. Ironically, the Russian Revolution had separated her from her family – she now depended on Picasso for everything.

Although socially ambitious, Olga lacked the fire of a dedicated dancer. Similarly, she didn’t appreciate her spouse’s passion for painting. She tried to tame Picasso into a suitable husband while he continued his bohemian ways. Shortly after she gave birth to their first child, Paulo, in 1921, she started suffering from unknown gynaecological issues. Picasso looked for another lover, and found her in the 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter, whom he hid from sight. As Olga was entitled to half the contents of his studio, Picasso never made a legal break from his wife. She fixated on him for years, sending him hate-filled letters on a daily basis, and trailed him around Europe, living on the periphery of his life, stalking and harassing his subsequent lovers for years to come.

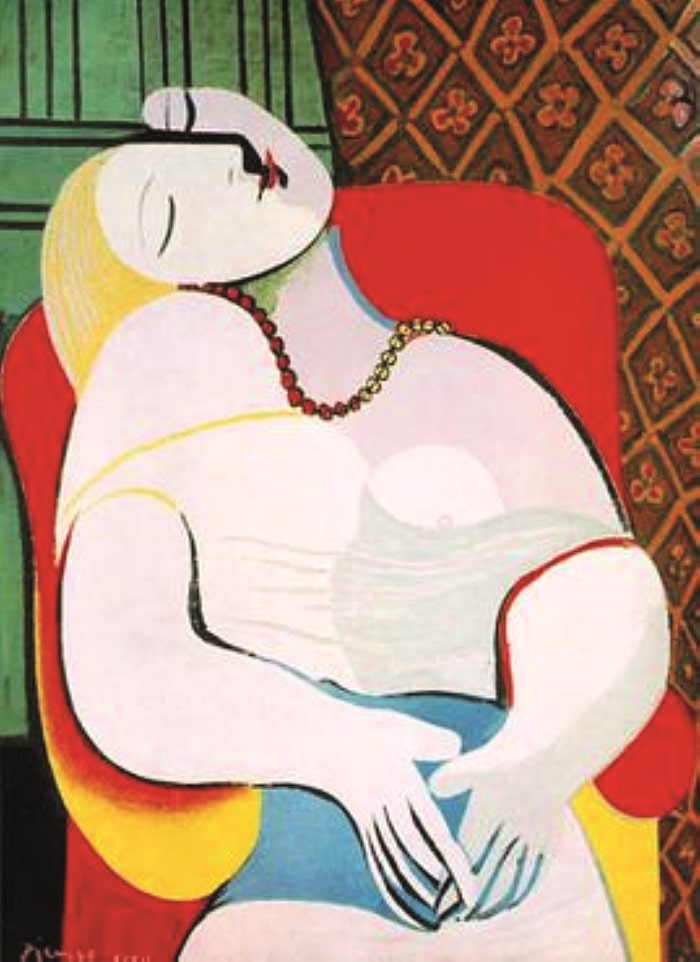

Marie-Thérèse Le Reve (1932) by Picasso. Credit: Succession Picasso DACS London, 2018

Marie-Thérèse Walter 1927-1935

The phrase ‘I am Picasso’ meant nothing to the teenage Marie-Thérèse Walter when Picasso approached her outside the Galeries Lafayette in Paris. The blonde 17-year-old was sturdy and athletic: to Picasso, the contours of her face and the strength of her form represented the ideal woman. He based a copious amount of work around Marie-Thérèse, tenderly displaying her curves with accents of eroticism. Although her name was kept secret for many years, she was the principal muse during Picasso’s Abstract period and can be seen in the brightly-hued painting Le Rêve (1932).

In 1935, the couple’s much-cherished daughter, Maya, was born. Picasso kept Marie-Thérèse and Maya housed near his own home, safely out of the way of his other women. As her time as Picasso’s muse wound to a close, she found herself sharing him with the Surrealist photographer Dora Maar. When the two women demanded he make a choice, he encouraged them physically to fight over him. He remarked later that it was one of his favourite memories.

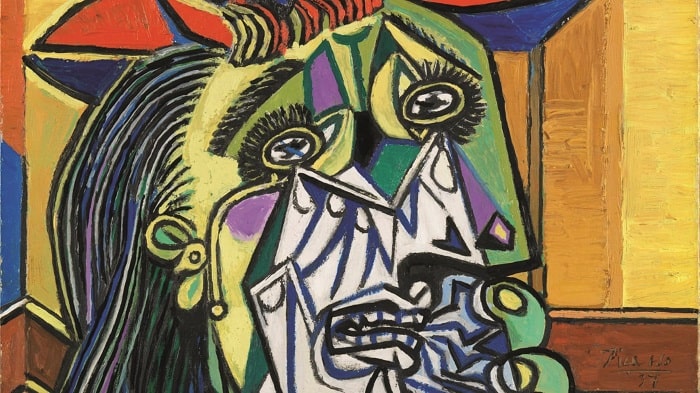

A fragment of Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’

Dora Maar 1935-43

Sitting at a table at Les Deux Magots, Picasso watched as the intense Dora Maar wildly jabbed a penknife between the splayed fingers of her gloved hand. His infatuation was complete when he introduced himself and she answered him in Spanish. The headstrong Maar was a card-carrying Surrealist. A photographer and an anti-fascist activist, she challenged Picasso intellectually in ways Marie-Thérèse could not. Maar photographed the process of Picasso’s 1937 mural Guernica and was the muse for The Weeping Woman. After steering her towards abstract painting this seemingly natural pairing of artists fizzled out around 1943. Picasso’s heart and mind were filled with another, younger woman. Maar fell into a severe depression and sought psychiatric help. After a period of treatment she became a Catholic, nun-like in her demeanour, and made the statement, “After Picasso, only God”.

Françoise Gilot 1943-52

When she met the 61-year-old Picasso in 1943, Françoise Gilot was an art student of just 21. Despite the 40-year age gap, their relationship went on to resemble a traditional family life and the couple had two children together, Claude and Paloma. Françoise’s life, however, was marred by Picasso’s wife, Olga, who relentlessly attacked her on the streets and even in the corridors of her own house, intimating “I had him first!”.

Picasso wasn’t troubled with yet another angry triangle he had created. Declaring, “I am not a submissive woman,” Gilot separated from Picasso, who had told her, “For me there are only two kinds of women: goddesses and doormats.” Known as ‘the woman who said no’, Gilot went on to write her memoir, Life with Picasso, a candid and fascinating record of the artist’s relationship with women. Despite Picasso’s sabotage attempts (he tried to dissuade galleries from buying her work), Gilot was a successful artist in her own right, and in 2010 she was made an Officier de la Légion d’honneur for her work in art and culture. At 99, she is still going strong.

Jacqueline Roque. Credit: Musee Picasso Paris

Jacqueline Roque 1953-1973

In 1953, the young Jacqueline Roque worked at the Madoura Pottery where Picasso created his ceramics. After the death of Olga Khokhlova, she became his second legal wife. Picasso based more works on Roque than on any of the other women in his life: she was the inspiration behind more than 400 pieces. Together until his death in 1973, Roque went on to manage his estate, bitterly feuding with Gilot and refusing to allow her or her children to attend Picasso’s funeral. Eventually the two women reconciled, collaborating on the foundation of the Musée Picasso in Paris.

There are other women, too, whose lives became entangled with Picasso’s. There was the mysterious Madeleine, his lover and model who terminated her pregnancy with him when she was replaced by Fernande Olivier. There’s Raymonde, the adolescent girl Picasso and Fernande adopted, who having become of interest to Picasso, was swiftly sent back to the orphanage. The year 1916 was a busy one for Picasso. He proposed to, and was refused by, Gabrielle Lespinasse, the “ravishing” mistress that he had secreted away while Eva was dying. Pâquerette, an artists’ model and mannequin for fashion designer Paul Poiret, was his summer girlfriend. The poet Guillaume Apollinaire helped Picasso kidnap Irène Lagut, with whom he’d fallen in love; she was indifferent although, having escaped, she returned to him a week later. In 1954, Picasso painted a series of portraits of Sylvette David, a blonde beauty with a signature ponytail. Their relationship, for once, was completely hands-off.

Picasso’s death left a trail of destruction. His children’s lives were in a tragic state. Marie-Thérèse Walter hanged herself four years after Picasso’s death and Roque fatally shot herself. Gilot suggested that Picasso was a narcissist with a desire for control: his seduction was a form of exercising power over women. Picasso wrung all he could out of his muses and then hung them out to dry on his canvases.

From France Today Magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Art history, art in paris, Dora Maar, Picasso

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY