Suzanne Valadon: Artist and Muse of Montmartre

A muse for the artists of Montmartre and a pioneer for female painters – and single mothers – around the world, she rose from humble beginnings to achieve fame and fortune. Hazel Smith traces her life from street urchin to celebrated artist…

Right at the crest of Montmartre, tucked away behind the cobbled tourist magnet of the place du Tertre, is the rue Cortot. At number 12 is the famous Musée de Montmartre, which was once the address of Suzanne Valadon’s studio and apartment. Within these walls, she juggled life and love, highs and lows.

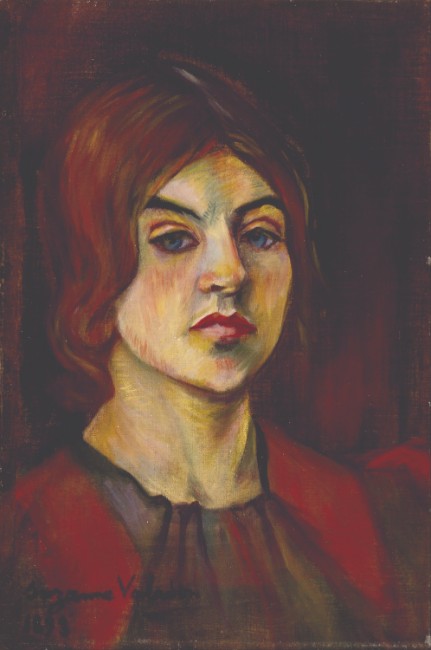

This self-portrait by Suzanne Valadon is dated 1898, when she was 33. Credit: Museum of Fine Arts Houston. Gift of Audrey Jones Beck

She was an eccentric live wire who personified the neighbourhood of Montmartre. An urchin of its streets, she became an artist’s model and her face is recognisable in a range of works. She was the teenage muse of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes; she was idealised on the canvases of Pierre- Auguste Renoir; and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec accurately captured her sardonic side. She also later became a boundary-breaking artist in her own right.

Marie-Clémentine Valadon was born in 1865 to an unmarried laundress in the village of Bessines-sur-Gartempe, Haute-Vienne. She and her mother arrived in Paris just as Baron Haussmann’s broad strokes were sending the city’s artists scurrying up to Montmartre, where studios could be rented for a fraction of the prices now being asked on the new avenues. Café life in Montmartre soon became a carousel of artists sharing opinions on painting, poetry and prose long past absinthe o’clock. Yet, although it was becoming a retreat for émigrés, Montmartre still retained the air of a village. It was easier to breathe here; stray dogs and street children survived happily enough. “The streets of Montmartre were home to me,” Valadon is quoted as saying in John Storm’s classic biography The Valadon Drama. “It was only in the street that there was excitement and love and ideas – what other children found around their dining room tables.”

Rue Cortot, Montmartre. Photo: Hazel Smith

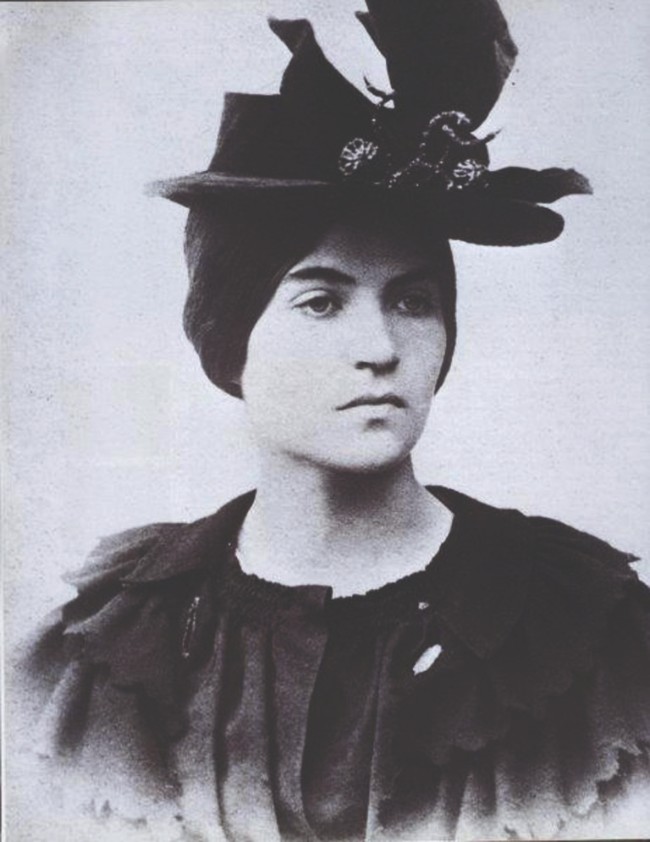

VALADON THE CHILD

The young Marie-Clémentine loved to draw, on any surface – the pavement, her mother’s walls – with coal scrounged from local merchants. An intrepid truant, she slipped easily over the confining walls of her convent school to roam the streets, drawing, playing or performing acrobatic stunts – a skill which, by the age of 14, had won her a position at the Cirque Molier. She was an agile gymnast – and equestrian – until a fall from the trapeze put an end to any dreams she may have had of life as a circus performer. Yet, her lithe form attracted the artists inspecting the model market of Montmartre, a chaotic beauty pageant ringing the fountain at the place Pigalle. The artists knew her as Maria. She was elfin, just five feet tall, but her striking blue eyes beguiled them from under a tousle of cognac-coloured hair. Pierre Puvis de Chavannes was an early employer. She posed for all the characters in The Sacred Grove, Beloved of the Arts and the Muses, which took him five years to complete. Puvis de Chavannes introduced her to the amiable Renoir. With kindly eyes and a sunny disposition, he was a favourite of the montmartrois.

Photographic portrait of Valadon circa 1885. Photo: Jean Fabris

The creamily exquisite Suzanne fell in with Renoir’s usual ‘family’ of models and he employed her several times, most notably in his 1883 series of dance paintings. She is the model for both La Danse à Bougival and Danse à la ville. She posed for the third in the series, but rumours of an affair so incensed Renoir’s betrothed, Aline Charigot, that in a fit of jealousy she scraped Valadon’s face off the canvas and entreated Renoir to replace it with her own. Plump Aline now mocks Suzanne from Danse à la campagne.

La Danse à Bougival, Renoir, 1883

Valadon’s face glowers from two of Toulouse-Lautrec’s works, Poudre de riz and La Gueule de bois (The Hangover). He was her closest confidant. Meanwhile, his fabulous posters promoting Montmartre were drawing more curious pleasure seekers to the hill. The atmosphere of the neighbourhood was became more sordid. The chaotic whirlwind of the Moulin Rouge, the Moulin de la Galette and the Folies Bergère caught Valadon in a current of excess and pleasure, during which she apocryphally slid naked down the banister at the Moulin Rouge wearing only a mask to cover her identity.

Poudre de riz, portrait of Valadon by Toulouse- Lautrec, 1887. Credit: Van Gogh Museum

Valadon had fallen into a routine of posing for older artists before falling into their beds. It was Toulouse-Lautrec who noticed the similarity between the teenage model and the heroine of the Bible story ‘Susanna and the Elders’, in which the beautiful Susanna had to fend off the sexual advances of two lewd, old voyeurs who had watched her bathe naked in her garden. As Maria had posed for Puvis de Chavannes, Renoir and others who were 20, 30 and 40 years her senior, the name fit. The young model and budding artist became Suzanne.

By the age of 18 she had given birth to a son, Maurice. In The Valadon Drama she states: “I don’t know if the little fellow is the work of Puvis de Chavannes or Renoir”. But it was the magnanimous Miguel Utrillo who was willing to take on the role of father, signing paternity papers eight years later, saying: “I’ll sign my name to the work of any of those men”. Raising Maurice Utrillo through childhood and beyond would become Suzanne’s greatest struggle.

The studio Suzanne Valadon shared with her son Maurice Utrillo. Photo: Hazel Smith

VALADON THE ARTIST

Valadon may have been flippant about her lovers, but she was serious about her intention to become an artist. She surreptitiously learned the artists’ techniques during her long hours of posing. When the bemused Toulouse-Lautrec found out that she drew, he pinned her works to his wall and dared his visitors to guess who their creator was. When Renoir happened upon her working on a self-portrait, he was amazed. “You too?” he asked. “And you try to hide it?” Toulouse-Lautrec introduced her to Edgar Degas, her first buyer – he bought a chalk drawing on the day they met. “That day,” she said, “I had wings.” On his smoke-stained walls, Degas – whose nicknames for her included ‘Illustrious Valadon’, ‘Terrible Maria’ and ‘Ferocious Maria’ – hung her works next to Ingres, Delacroix, Manet and Gauguin. “You are one of us,” he said.

The studio Suzanne Valadon shared with her son Maurice Utrillo. Photo: Hazel Smith

With Degas as her biggest supporter, Valadon’s confidence grew. An accepted part of his household, she called in at 37 rue Victor-Massé every afternoon. He arranged for her work to be promoted by two of the most influential art representatives in Paris, Paul Durand-Ruel and Ambroise Vollard. Vollard staged Valadon’s first solo show. In 1894, Degas suggested that she display her drawings at the prestigious Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. Valadon was the first woman ever to be admitted to the exhibition. It was simply unheard of. Very few professional artists in the 19th century were women, but Valadon was kicking down the walls that had always hindered her sex.

Valadon is chiefly famous for her treatments of the female nude. Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art

While contemporary artists such as Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, with their wealthy, supportive families, were cloistered from real Parisian street life, Valadon had an entrée to the cafés and cabarets, which forever remained fermés à clé to her well-heeled female peers. Valadon from Montmartre could talk the talk and walk the walk, rendering harsh but honest images of people from her daily life.

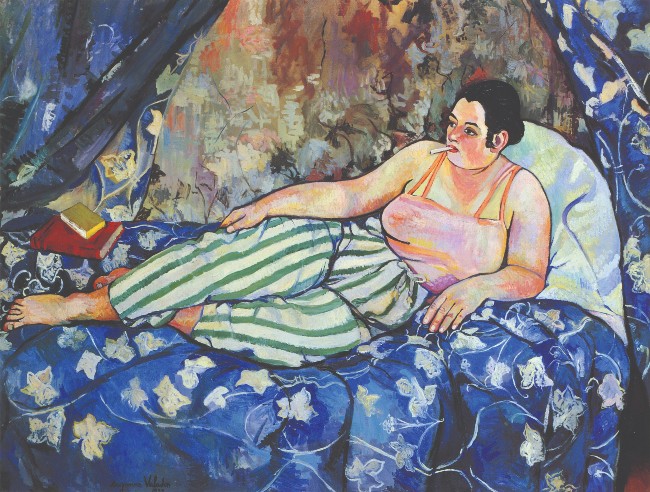

La Chambre bleue, Valadon, 1923. (C) Centre Pompidou

Her artistic output dwindled when she married the established bourgeois Paul Mousis. Mousis was completely unlike the bohemian draughtswoman, but he provided the stability she lacked. He moved Valadon’s family to a house in the suburbs, yet generously rented for her the studio at 12 rue Cortot. It took 13 years of married life for her to realise that she wasn’t cut out to be a rich man’s wife – and to fall in love with one of her son Maurice’s friends, André Utter. Twenty-one years her junior, the artist and electrician lit up Valadon’s life. He was in the prime of life – a strong, smooth, muscular jeune premier, and a joyful contrast to her old men. Inspired, Valadon took up painting again, exhibiting at a variety of salons. Breaking convention, she even painted Utter in the nude. Despite her affair she was able to keep the studio at 12 rue Cortot. Within its network of dim and creaking passageways, the family created an economical space for themselves. Visitors to the Musée de Montmartre can see their living quarters and their bright-windowed atelier, which still consists of a wood stove, old chairs, and stacks upon stacks of paintings, on the floor and aloft. An undisturbed paintbox sits by the window, with Maurice’s easel nearby.

Valadon, Utrillo and Utter in the studio

VALADON THE MOTHER

Maurice Utrillo was a delicate child. He was withdrawn, his moods mercurial. He became an alcoholic at a very young age, the habit stemming from the boozy cures his grandmother had given him to temper his rages. As an adult he continued to mollify his anxieties with alcohol, which served only to create a cycle of drunken rampages and sullen sobriety, repeated dozens if not hundreds of times.

He escaped hospitals, asylums and prisons to cadge a drink. Maurice’s doctor urged Valadon to teach him her craft. Maurice went on to build an extremely lucrative career from painting Parisian street scenes, but it did nothing to lessen his eccentric behaviour. It would take over 50 years for Maurice to find some sense of inner peace.

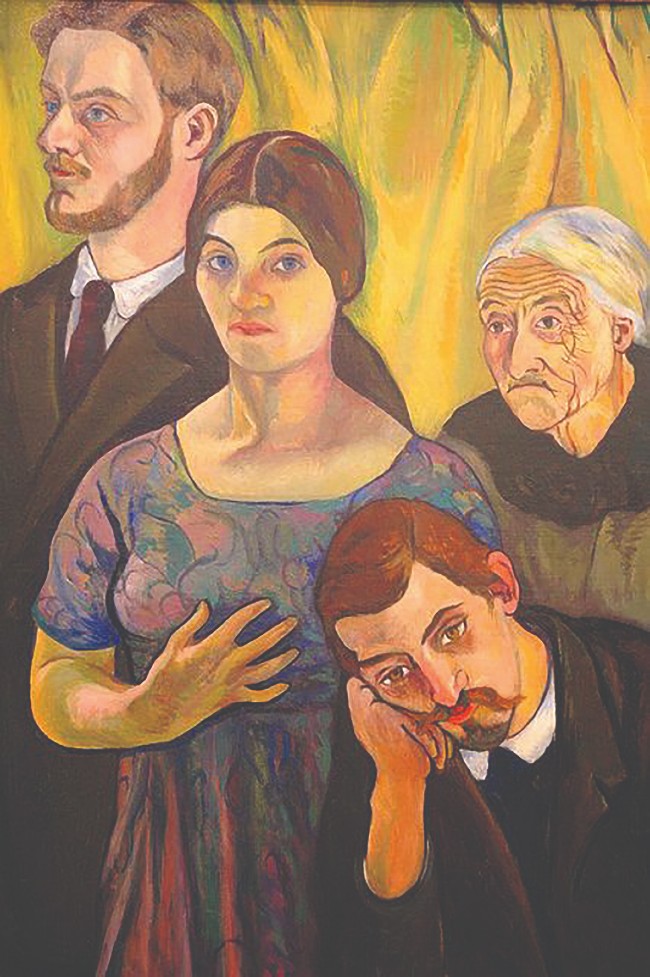

Valadon, her fractious son and young lover were Montmartre’s ‘unholy trio’. Valadon never looked or acted her age. Utter said of her: “She seemed to dance rather than walk. She was something of an Amazon and a fairy”. She was seen in the Montmartre tavern Au Lapin Agile – where her and her son’s work hung on the walls – wearing a corsage of carrots with a lettucey bouquet alive with snails.

Portrait de famille, Valadon, 1912. (c) Centre Pompidou

As a fatherless single mother, women were the dominant sex to Valadon. Her elders taught her art through the male perspective, but she knew better than that. Her personal style was defined by bold contours and rich colours. She wasn’t a Realist, a Fauvist or an Expressionist. She simply painted what she knew. Her nudes were candid, but because she did not idealise her subjects they did not titillate. Tension and imperfection are tangible in Valadon’s Family Portrait of 1912. This tension is echoed in her Blue Room and Reclining Nude, painted in 1923 and 1928 respectively. In 1924, Valadon and Utrillo were jointly paid an astronomical amount by the art dealer Alexandre Bernheim-Jeune. This retainer made them wealthy enough to buy a car and a tumbledown castle, complete with moat and drawbridge. Their cat supped on caviar once a week. They were able to move into a modern house on the rue Junot.

Valadon lived in the vortex of the bohemian world of Montmartre. History would not be the same for the famous female denizens of the newly popular Left Bank if Valadon hadn’t paved the way for them to be the mistresses of their own sexuality – and the mistresses of their own vocations and avocations.

From France Today magazine

Photo of Valadon with her dogs

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY