Behind the Brand: A Tale of Two Confectioners

How a confectioner in Paris led to the founding of a luxury chocolate shop in London.

On both sides of the Seine are branches of Maison Boissier, where gold-wrapped marrons glacés and fruit-flavoured bonbons in round decorated boxes, and tins of pastel pink or bright blue are sold to Parisians and passing tourists. Across the Channel, at London’s Royal Arcade in Old Bond Street, a shop sells dark chocolate crowns and dusted Marc de Champagne truffles in round pink and oblong white boxes labelled Charbonnel et Walker in fancy gold letters. The history of these two establishments is a shared one and perhaps visually obvious, given the similarities in their packaging. One was hatched from the other, and their longevity reflects our taste for luxury artisan chocolate and sweets and is testament to the inventiveness of the makers who produce them.

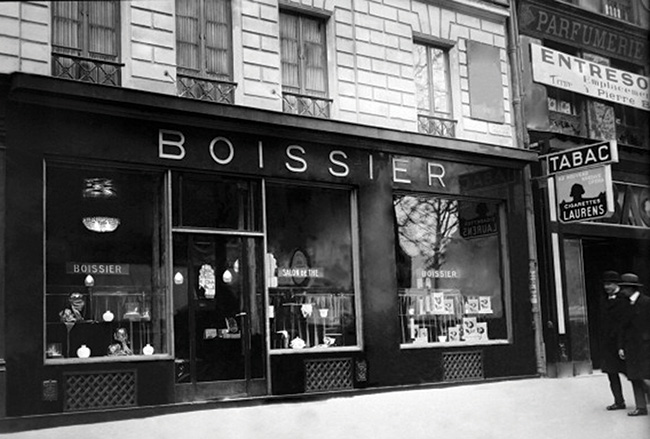

The Maison Boissier shop front in 1929 © Charbonnel et Walker

Boissier Beginnings

Pierre-Bélisaire Boissier (1810-1890) arrived in Paris from Puyréaux, in the west of France, ambitious to make his mark in the world of confectionery.

To begin with, life in the capital was hard and he was sleeping beneath a stairway, but his perseverance paid off and by 1835, he’d achieved his aim with the founding of Maison Boissier. It began as a stall on Boulevard des Capucines, later becoming a shop at no 9, before multiplying along the main thoroughfares of ‘the beautiful arteries of Paris’.

Boulevard des Capucines in 1870, where Maison Boissier began © Charbonnel et Walker

The confectioner became well-known among the elite for his fruit-flavoured boules, as smooth and round as marbles; his pastilles flavoured with mint, rose and jasmine; a pineapple version known as ‘le bonbon des théâtres’ because it was customary to take such sweets along to suck during the interval; and his marrons glacés. Victor Hugo was one of several writers who praised the quality of Maison Boissier’s products in purple prose: “It’s thanks to Boissier, my doves, that we fall happily at your feet; the strong are conquered by bombs and the weak with sweets.”

Boissier bags from 1894 © Charbonnel et Walker

With such an illustrious following it became a Boissier tradition to name a new sweet at the start of the year in honour of a theatrical or literary success from the previous 12 months. The ‘Salammbô’ brought out in 1863 was named after Flaubert’s novel of the same name, which in 1890 became an opera by Ernest Reyer. It is a tongue-shaped petit four, coated with cream and sugar and sometimes scattered with chopped pistachio at either end.

In 1879, Marie Duplessis, the muse of La Dame aux Camélias author Alexandre Dumas fils, took some Boissier sweets to the theatre. The company could not have wished for better publicity and in the archives its catalogues feature sweet bags made of satin for this purpose, embroidered with the word ‘Opéra’.

Boissier bonbons fleurs in a blue tin © Charbonnel et Walker

Box of Delights

The Boissier pastilles and boules came in bags and boxes that were a marvel of craftsmanship and artistry which continued under Boissier’s successor, Cyrille Robineau. Surprising as it might seem today, Maison Boissier’s packaging took the form of elaborately decorated miniature chests made of papier-mâché or tortoiseshell with mother of pearl inlay, intended to be kept as mementoes after the confectionery jewels inside had been eaten. Light in weight, these containers also had locks and keys, suggesting the cost and luxury status of the delicacies they held. And this was not all: silk pouches were made for the sweets and skilled illustrators were commissioned to create the publicity designs.

Boissier wooden sweet box from 1856, covered with papier mâché © Charbonnel et Walker

Charbonnel et Walker

Mademoiselle Virginie Eugénie Charbonnel (1848 – 1926) learnt her trade at Maison Boissier, where she rose through the ranks to become forewoman, and it’s possible that it was here, in Paris, that she met her future partner, Minnie Walker from Jersey.

In 1875, the two women set up their own shop in London, which they called simply Charbonnel et Walker. Virginie, then only 27, was encouraged by the future king, Edward VII, to make this brave move abroad: he told her it would be the first Parisian shop in the British capital. The new enterprise was marketed as: ‘Parisian Confectioners and Bon-Bon Makers; Ex-premières de la Maison Boissier de Paris’.

Virginie Eugénie Charbonnel © Charbonnel et Walker

To begin with, Virginie and Minnie ran their business from where they lived at No. 5 Clarendon Mansions on fashionable Bond Street. Virginie focused on chocolatemaking, while her partner concentrated on designing and creating the fancy boxes and gift bags. One of the first chocolates Virginie thought up was a dark chocolate crown, an interesting choice given the turbulent history of royalty in France, although perhaps it was a nod towards the aforementioned Prince of Wales. The Plain Crown (no. 1 of the numbered chocolates in today’s Charbonnel et Walker Heritage Collection) is concocted from a recipe of dark chocolate, blended marzipan, whisky and hazelnut praline centre. Other favourites from 1875 are the English Rose and English Violet creams (numbers 4 & 5 in the present-day collection) with soft fondant centres and crystallised petals on top.

Minnie Walker’s contribution included a pink satin gift bag embroidered with flowers and sequins filled with chocolates for special occasions. As with Maison Boissier across the water, the shop became renowned for its high-class, exquisite packaging. One journalist observed: “When the bonbonnière is empty of its sweet contents, the box will form either a jewel casket or a handkerchief box…”

Charbonnel et Walker’s Canary Wharf shop © Charbonnel et Walker

A Court Case, A New Confectioner & A Tea Room

The partnership between Virginie Charbonnel and Minnie Walker was short-lived. In 1877, Virginie married a wine merchant, Samuel Levy, and a year later decided to return to France. Minnie acquired the rights to continue trading under the company’s old name. Her former partner objected, however, and brought a law suit against her to prevent her using it – which she lost.

Both women kept on with their confectionery businesses on either side of the Channel. In Paris, Samuel and Virginie opened La Confiserie Charbonnel – nicknamed Le Palais des Bonbons – at 34 Avenue de l’Opéra. It was a grand affair. They commissioned a theatre architect Charles de Lalande to build a boutique of gold ornamentation, frescoes, mirrors and a grand staircase. “When my customers come in, I want them to think they’ve walked into a fairytale called Le Bonbon,” the confectioner declared. Ironically, in terms of style, client base and product, La Confiserie Charbonnel found itself in direct competition with Virginie’s former employers, Maison Boissier.

Charbonnel et Walker’s Canary Wharf shop © Charbonnel et Walker

Capital Success

Meanwhile, back in London, Minnie Walker was also enjoying sweet success. She had opened a tearoom on Bond Street and was granted a licence to sell wine as well as running the chocolate shop. Its reputation for luxury was evident when Leopold de Rothschild married Marie Perugia in 1881 and Charbonnel et Walker provided the white satin bags embroidered with ‘Leopold et Marie’ and filled with delicacies. In parallel to Victor Hugo in Paris, Oscar Wilde declared in 1890, “The House of Charbonnel is one of the oldest ministrants to the taste for sweets and upon their counters shall be found the latest dainties…”.

While La Confiserie Charbonnel did not see out the 19th century, its predecessors, Maison Boissier in Paris and Charbonnel et Walker in London, survived. Maison Boissier retained the distinctive look of its tins and boxes while trying to straddle the difficult line between tradition and modernity. Today, it sells marrons glacés infused with cognac, rum, pear, vanilla or chocolate; its bonbon boules come in all variety of flavours from lime to blueberry, and its chocolate petals were used in 2014 to decorate the dress of Éliette Abécassis at the Salon du Chocolat in Paris.

Charbonnel et Walker Boîte Blanche © Charbonnel et Walker

Interestingly, Charbonnel et Walker in London styles itself as an iconic British brand, with its flagship store at The Royal Arcade, Old Bond Street, not far from the site of its 1875 original.

The chocolates are made in a factory in Poundbury, Dorchester, on Duchy of Cornwall land, and handpacked, and among the company’s best-sellers are the Pink Marc de Champagne Truffles and the Milk Sea Salt Caramel Truffles.

Historically, the shop has had a following among literary types: in the 1920s, Noel Coward hired a railway carriage and sent a footman to London for a box of chocolate almonds, and the Bloomsbury Group were also known to be partial.

In 1970, Charbonnel et Walker was granted The Royal Warrant as Chocolate Manufacturers to Her Majesty the Queen, whose coat of arms appears on the boxes (obviously this might change following the death of Elizabeth II). Perhaps most charming of all, there is a chocolate called Pomponette (number 25 in the Heritage Collection), which is a dark chocolate with marzipan and puree of pistachio nuts, named after Virginie Charbonnel’s cat. That, surely, must make it the cat’s whiskers.

Delicious pink champagne truffles © Charbonnel et Walker

Chocolate Box of Facts

1615: 14-year-old Anne of Austria, daughter of Philip III of Spain, brought a gift of chocolate to her betrothed in France, the 14-year-old King Louis XIII. It arrived in a chest, which suggests its great value.

1760: Chocolat Lombart, the first manufacturer of chocolate in France, was founded. The company lasted almost 200 years before being absorbed by Menier Chocolate in 1957. A Lombart chocolate box survives from the time of Louis XVI containing chocolate tablets made with nougat cream.

1800: The first chocolate shop to open in Paris was called Debauve & Gallais on Rue des Saints-Pères (now a protected monument). Debauve was a former chemist to King Louis XVI who mixed medicine for Queen Marie Antoinette into a paste of cocoa and cane sugar to make it more palatable. The Queen called these coin-shaped chocolates pistoles.

1903: Confectioner Anton Rumpelmayer founded a tea house with his son, René, on Rue Rivoli. He named it Angelina after his daughter-in-law. Coco Chanel liked to go there and its famous hot chocolate, L’Africain, is still served.

1998: The Académie Française du Chocolat et de la Confiserie was founded to preserve the art of French chocolate. France has welcomed chocolate into its cuisine, particularly its pastries. It was here that the pain au chocolat and the chocolate éclair were born, the latter invented by the famous French chef Antonin Carême (1784-1833).

From France Today magazine

Lead photo credit : Charbonnel et Walker Pink Marc de Champagne Truffles (lightly dusted pink truffles with a milk chocolate, butter and Marc de Champagne centre) © Charbonnel et Walker

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Food, French chocolate, French chocolatiers, French food

By Deborah Nash

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY