In the Footsteps of Madame de Pompadour

Chloe Govan delves into the life of King Louis XV’s mistress and reveals her controversial role as a revolutionary in the worlds of art, politics and religion

In the final portrait of Madame de Pompadour, before she died at the age of just 42, her serious and reserved demeanour disguises a former life of scandal and stormy political subterfuge. In the painting, she displays calm, demure, almost glassy eyes and conservatively pursed lips. Yet, beneath this outward appearance of virginal innocence and virtue lies a thrilling past as the official mistress of King Louis XV.

Her life began in 1721 as Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, the daughter of a promiscuous mother and a penniless fraudster father who was forced to flee the country when she was just four years old to avoid the death penalty for his debts. Charles François Paul Le Normant de Tournehem, a wealthy tax collector rumoured to be her biological father, became her legal guardian.

Madame de Pompadour by François Boucher, 1754

Her destiny as the King’s favourite was sealed, or so many believed (herself included), when she turned nine and a fortune teller confidently predicted she would one day “reign over the heart of the King”. Eerily accurate prophecy or eye-roll-worthy cliché? Either way, fate initially led her in a different direction as her guardian arranged her marriage at the tender age of 19 to his nephew, Charles-Guillaume Le Normant d’Étiolles.

But Jeanne-Antoinette never forgot the fortune teller’s promise. When she and her husband acquired a château near the King’s hunting lodge, instead of settling into gentle married life, she paraded audaciously on horseback, hoping to catch the monarch’s eye. She deliberately crossed his path on hunt days without success until, at last, in 1745 she was invited to a costume ball at the Palace of Versailles.

courtesy of the Chateau de Versailles

GODDESS OF THE HUNT

The King arrived dressed as a yew tree, with seven royal servants joining the branches. Jeanne-Antoinette came dressed as Diana, the Roman goddess of the hunt, and made her move. Dramatically unmasking himself, Louis declared that he reciprocated her feelings – and within a month she had abandoned her husband and daughter, moved into her own private apartment in the palace, directly above the living quarters of the King, and was given the title of the Marquise de Pompadour.

Lacking desire for her husband, Queen Marie – who cared far more about power than romance – readily accepted her love rival without jealousy. Pompadour seemed to lack ego too, making herself indispensable as her queen’s lady-in-waiting. Yet, while the royal marriage was little more than a formal arrangement, genuine passions were ignited between Louis and his mistress. In answer to rumours circulating around the court about their love life, the King allegedly had the traditional French champagne glass moulded into the shape of one of her breasts. He also commissioned the ‘marquise diamond’, designed in the shape of her lips.

Queen Marie. Credit: Wikimedia commons

All of this romantic symbolism made them the top exhibitionists of their time. Pompadour was also known for her extravagant backcombing, giving birth to the enduring hairstyle in her name.

The King’s mistress wasted no time in sparking controversy. She supported and aided the creation of the first French Encyclopedia, to the rage of the Catholic Church, which strived to have it banned. It openly discussed the Scientific Revolution, challenged the legitimacy of the ruling class and promoted intellect and reason ahead of religion – and those who sought to instil ignorance for the purpose of manipulation were petrified.

Worse, she was utterly unapologetic about her endeavours. Counting Voltaire among her closest friends, she made waves in literary and political circles and championed free thought. But her political leanings and views had catastrophic consequences and would spell the end of her reign over the public’s affections. As a close adviser to Louis, she prompted him to break a peace treaty with Prussia and partner with Austria instead. Soon after this decision, France suffered a humiliating defeat in the Seven Years’ War.

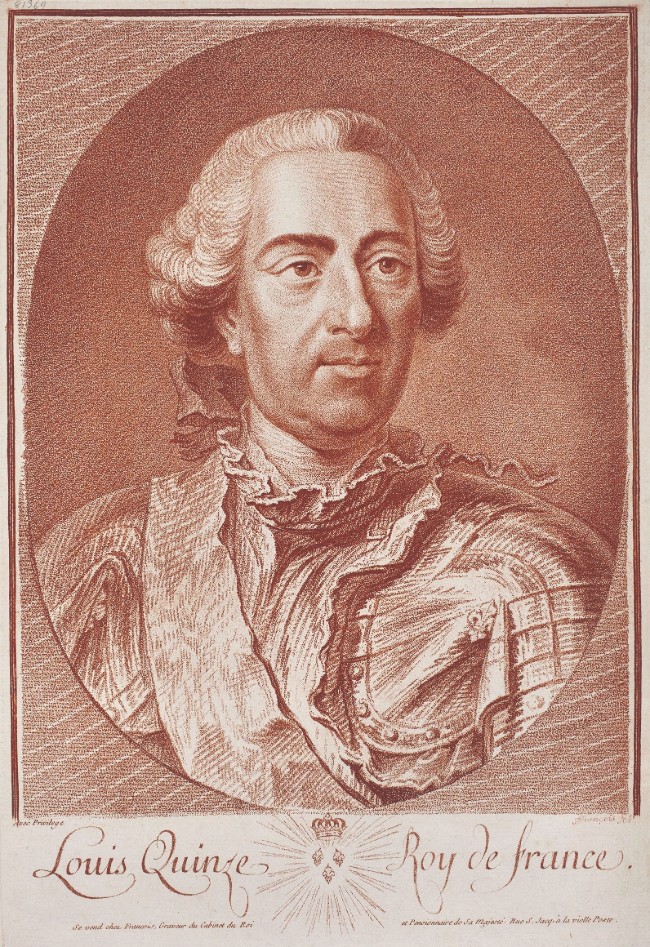

King Louis XV of France. Credit: Wikimedia commons

Those wishing to follow in the footsteps of this revolutionary can visit Versailles and the royal châteaux of Fontainebleau and Compiègne. She spent time in all three and helped oversee the design of the latter two. Her famous Paris mansion, the Palais de l’Élysée – a gift from the King – is now off-limits as the official residence of the French president. That said, those with deep enough pockets can enjoy the next best thing – the Pompadour treatment – at five-star Hôtel Le Meurice, where a suite has been created in her name.

Aficionados may also be keen to delve into her passion for porcelain at the Manufacture nationale de Sèvres porcelain museum and factory, a few miles from Paris.

Sèvres porcelain

A fervent patron of the arts, she was instrumental in establishing Sèvres porcelain as the luxury object of choice throughout the 18th century. In an attempt to bring Sèvres into the favour of her King, she commissioned an interior garden comprised entirely of porcelain flowers. Thanks to her efforts, in 1753 Louis XV declared Sèvres a Royal Factory. Four years later, the factory named a soft shade of pink, Rose Pompadour, in her honour.

But her contribution to the arts did little for her reputation. The controversial maîtresse royale was one of the most reviled women in the country by the time she died of tuberculosis in 1764. Yet it had been a grave mistake to dismiss the King’s mistress as just another vacuous seductress. More than any other favorite du roi, she had revolutionised French society.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in King Louis XV, Madame de Pompadour, Versailles

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY