In Search of Monsieur Proust in Paris

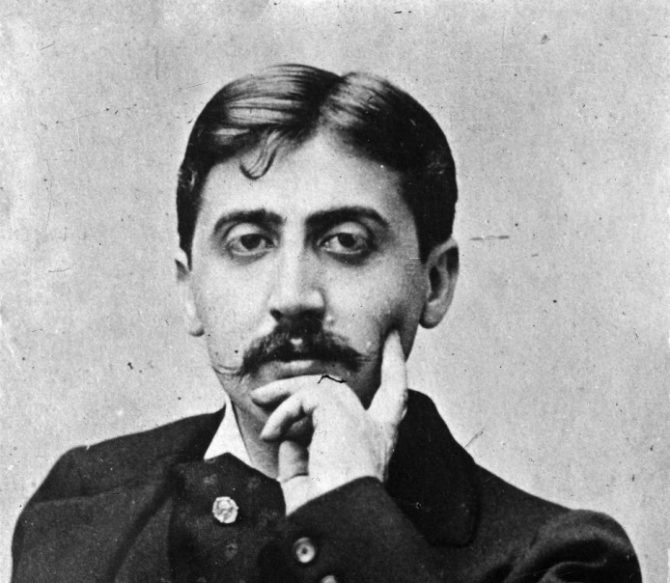

On the western side of the Right Bank, the Paris of Marcel Proust is a mostly leafy neighborhood, graced with golden hues, lovely on a fine autumn morning. It’s the Paris of the “beaux quartiers” laid out during the Second Empire and completed around the turn of the 20th century, during the Belle Epoque that coincided with most of Proust’s lifetime, 1871–1922. It’s also the setting of his seven-volume epic novel A La Recherche du Temps Perdu (Remembrance of Things Past, or In Search of Lost Time).

It was a time of profound mutations. Proust would have seen the arrival of electricity, running water, elevators and the telephone; the replacement of horse-drawn tramways by steam, and then by electricity; and the arrival of the automobile. He lived through the golden age of Universal Expositions, and witnessed the construction of the Eiffel Tower in 1889, and the Grand and the Petit Palais, the Gare d’Orsay and the first Métro line, all in 1900.

On September 3, 1870—the day before the fall of the Empire during the Franco-Prussian War—Proust’s parents were married in the old Mairie of the unglamorous 10th arrondissement, where his mother Jeanne Weil’s family lived at 40 bis rue du Faubourg Poissonnière. The Mairie remains at 72 rue du Faubourg Saint Martin, but the present flamboyant neo-Renaissance building replaced the old one in the 1890s. Jeanne’s stockbroker father Nathé Weil was the son of a prosperous Jewish porcelain manufacturer from Lorraine who settled in the 10th because it was the gateway to Lorraine—via the Gare de l’Est railway station—and the Parisian center of the trade. (Until recently the rue du Paradis was brimming with porcelain and crystal outlets, most famously Baccarat.)

Proust was hardly keen to mention his ties to the “sordid” 10th, although he admired the monumental arches of the Portes Saint Denis and Saint Martin. (How might he feel today about the ethnically diverse area, where Africa, Turkey and India converge?)

His father, Adrien Proust, the son of a Catholic shopkeeper from Illiers, near Chartres, was a brilliant epidemiologist who received the Légion d’Honneur from Empress Eugénie just a month before the wedding. The newlyweds settled at 8 rue Roy, in the new Haussmannian neighborhood near the nearly completed church of Saint Augustin. Ten months later, on July 10, 1871, Marcel Proust was born at 96 rue La Fontaine, his uncle Louis Weil’s home in Auteuil, where his parents took refuge during the street fighting of the Commune, the Paris uprising that followed France’s defeat by the Prussians.

Proust never lived in Auteuil, despite the memorable childhood scenes set there in his work. The village of Auteuil had been annexed to Paris only in 1860, and was still countrified. Even in the 1890s there was plenty of unbuilt land, hence architect Hector Guimard’s legacy of sixteen Art Nouveau houses, including the famous Castel Béranger at 14 rue La Fontaine. Guimard’s own Art Nouveau townhouse is still at 122 avenue Mozart, around the corner from Proust’s birthplace. Uncle Louis’s house has long since been replaced by an apartment building.

For most of his life Proust lived at 9 boulevard Malesherbes, near the Madeleine church, where the family moved in 1873 after his brother Robert was born. The building still stands, as does the colonne Morris, the billboard pillar, across the street. Young Proust used to rush to it daily to see who was playing—hoping for Sarah Bernhardt. It was a new building with an elevator situated in “one of the ugliest districts in Paris”. The dome of Saint Augustin was its only saving grace; it could be seen from the apartment, giving “this view of Paris the character of certain views of Rome by Piranesi”. The first church in Paris with an iron frame, it was built by Victor Baltard, architect of the Art Nouveau market pavilions of Les Halles.

Proust’s school, the Lycée Condorcet, adjoined the church of Saint Louis d’Antin on rue Caumartin, where he was baptized. It was an excellent school with a multitude of famous brainy alumni. Poet Stéphane Mallarmé taught English, and composer Georges Bizet’s son Jacques was a classmate. Thursdays were off, spent, weather permitting, in the gardens of the Champs-Elysées, where Proust played with his sweetheart—in the novel redheaded Gilberte, daughter of Charles Swann and Odette de Crécy; in real life Marie de Benardaky, daughter of a Polish nobleman. The old Guignol puppet theater and the châlet de nécessité with its white tiles and mahogany cabin doors—the “little rustic theater”where his grandmother had a stroke—are still there.

In 1900 the family moved to 45 rue de Courcelles, near the Parc Monceau. Known as la plaine Monceau, it was the city’s wealthiest neighborhood. The private mansion at 63 rue Monceau belonged to wealthy banker Moïse de Camondo; replaced by an even grander mansion in 1912, it’s now the Musée Nissim de Camondo.

North of the park, on Place Malesberbes, the immense mansion of banker Emile Gaillard was modeled on the flamboyant Gothic Louis XII wing of the Château de Blois; the square is now Place du Général Catroux, and the building a branch of the Bank of France. Sarah Bernhardt lived on rue Fortuny which, along with the rue de Prony, was the province of actresses and courtesans. Those streets are still lined with astonishingly decadent townhouses well worth a detour. Odette de Crécy’s townhouse in La Recherche, on rue La Pérouse near the Etoile, would have looked much the same.

To the south, the Musée Jacquemart-André, at 158 boulevardHaussmann, the former home of banker and art collector Edouard André and his artist wife Nélie Jacquemart, recaptures the interior decor and lifestyle of respectable society. Proust was never a guest there, but he rotated in the same social circles, in which the ladies set the tone with their weekly salons. Geneviève Straus—daughter of composer Fromental Halévy, widow of Bizet and mother of Proust’s friend Jacques—had married the Rothschilds’ lawyer Emile Straus. Her salon was sought after even by old-guard residents of the Faubourg Saint Germain, who were willing to cross over into the territory of new money to be among her guests. There Proust met many socialites who would inspire his characters—Charles Haas was one of the models for Swann, the Comtesse de Greffulhe for the Duchesse de Guermantes. When Paris was raging over the Dreyfus case (1894–1906), the salon became the headquarters of the Dreyfusards. Proust wrote the first petition in support of Dreyfus; Degas and Debussy parted company with the salon.

By 1906, Proust’s parents had died, his brother had married, and he felt the family residence was too big. He moved to 102 boulevard Haussmann, a building owned by his Uncle Louis, where he wrote the bulk of his work, mostly in bed. Today the building belongs to the CIC bank, which has restored the bedroom, famously lined in cork for soundproofing, but the room’s contents are in the Musée Carnavalet, leaving the solitary chamber pretty soulless.

With his substantial inheritance, Proust became a man about town. Among his haunts, the restaurant Larue at 15 place de la Madeleine and Café Weber at 21 rue Royale are gone, but Maxim’s, at 3 rue Royale, is still a Belle Epoque beauty, albeit socially a pale shadow of what it once was. Above the restaurant, a museum displaying current owner Pierre Cardin’s collection of Art Nouveau furniture is infused with an atmosphere of decay symbolic of the Proustian world.

Not so the florist Lachaume across the street, where Proust daily bought a fresh cattleya orchid as a boutonnière. He also kept a room, which now bears his name, at the nearby Hôtel Ritz. In 1907 he gave a dinner there for Le Figaro director Gaston Calmet, who promoted his career, and to whom he had dedicated Swann’s Way.

The farthest reach of Proust’s Paris is the Bois de Boulogne. The horse-drawn carriages carrying ladies of varying degrees of respectability are gone, but the Bois is little changed. In the novel, Odette took daily strolls along the Allée des Acacias, where Proust occasionally dined at Le Pavillon d’Armenonville; today the Allée is Avenue de Longchamp, and Le Pavillon is used only for functions. Le Châlet des Iles—a rambling garden restaurant on an island in the Inferior Lake—is hardly evocative of a misty Breton landscape, as depicted in the book. But it still sits on its little island, charmingly accessed by a canopied, flat-bottomed boat. The most famous restaurant in the Bois, the three-star Pré Catelan, was a favorite of the novel’s heavily satirized, social-climbing Madame Verdurin.

In 1919 Proust’s widowed aunt sold the Haussmann building, and he moved to 44 rue Hamelin in the 16th, (now a three-star hotel), where he died on November 18, 1922—not far from where he was born. His funeral Mass was held in the Saint Pierre de Chaillot chapel on Avenue Marceau, now replaced by a larger church. Like so many residents of the beaux quartiers, including his parents, his brother and sister-in-law, Proust was buried in Père Lachaise cemetery.

From the France Today archives

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY