Great Travel Destinations: Martinique, Island of Queens

By 1763, the French had lost the Seven Years’ War, and it was time for the British to make their territorial claims in the New World. They had two real options: they could claim Canada, where France still ruled vast swathes of wilderness, or they could claim Martinique, which the British navy had already seized during the war. One had to go to the victors: France would cede either the ice-bound forests of Canada or the sun-drenched beaches of Martinique.

Historians now doubt the wisdom of France’s giving up Canada, but as I lounge in a Parisian-style sidewalk café, dawdling over my apéritif, I must question the verdict of history. Martinique is a Caribbean jewel: France on a sunshine island. Of course though, it was treasured by the French for more than its glorious weather. The largest (424 square miles) of the Windward Islands, it was a huge sugar producer, catering to Europe’s sweet tooth – and the pockets of the continent’s primitive dental profession.

French settlers – the Creoles – were the gentry of Martinique. They carved out more than 400 plantations across the island and dragooned tens of thousands of African slaves for soul-breaking work in the fields. The sugar they exported to France made them rich; the goods and cultural ways they imported created the French lifestyle we see today – the aspiration of these Creole gentry was acceptance in French society.

The Caribbean island of Martinique. Photo: Fotolia

In the 18th century, no plantation family needed a social boost more than that of Joseph Tascher. His home and crops were flattened by the great hurricane of 1766. For years thereafter, his young family was forced to live amid the clanging machinery of his stone sugar-processing building, which had miraculously survived. It was an inauspicious beginning for his eldest daughter, who would grow up to be Joséphine, Empress of France. But she was not the only girl of Martinique to make her mark on the world. Legend has it that the mother of Sultan Mahmud II, the great reformist Ottoman leader, was from Martinique. Then there was Françoise d’Aubigné, Louis XIV’s uncrowned queen, who spent her childhood years here in abject poverty. Finally, there was Hortense, the daughter of Joséphine, who became the Queen of Holland and the mother of Napoleon III, and who was both a disastrous ruler and an architectural genius who gave the world the Paris we know today. More about all of them later. First about the island these women grew up on.

In Joséphine’s time, the island’s commerce and culture revolved around the cities of Fort-de-France (then called St Louis) and Saint-Pierre. The former is today’s capital and commercial hub; the latter is testament to perhaps the worst natural calamity in modern history. Fort-de-France lies directly across the bay from Joséphine’s family’s 527-hectare spread at Trois-Îlets – water taxis connect the two. It is here that the imprint of metropolitan France on the island is deepest. Along the waterfront, the expansive La Savane is the city’s Tuileries Garden, complete with bandstand, play area and park-side cafés. Of course, Joséphine’s statue is also here – minus her head. Sadly, she has been beheaded not once but twice. It seems that some citizens chose to punish her statue in the traditional French manner for supporting the reinstitution of slavery on the island. Her “heads” now reside safely in City Hall.

The statue of Joséphine, without her head, in La Savane. Photo: Ken Harbinson

Architectural Prowess

Just across the road from Joséphine stands the ornate Romanesque-Byzantine Bibliothèque Schoelcher, honouring the man who finally ended the island’s slavery in 1848. During the Paris 1889 World Exposition, celebrating 100 years since France first became a republic, this building, together with the iconic Eiffel Tower, was erected as a showpiece of French technical and architectural prowess. Following the Exposition, it was taken stone by stone from the Tuileries Garden and transported here, to serve not just as a library, but as a Caribbean monument to French culture.

La Savane is guarded on one side by the battle-scarred Fort Saint-Louis, built in 1669 in the style developed by Vauban, the great French military architect. On the other side of the park is Old Town, where the maze of narrow streets and alleys packed higgledy-piggledy with small shops, markets and restaurants creates a Caribbean version of the Left Bank or Marais.

The Bibliothèque Schoelcher once stood in the Tuileries Garden in Paris

Saint-Pierre once had this same vibrancy. It was known as the Paris of the Antilles. Today, it is a lazy, picturesque seaside town where visitors come to lounge in outdoor cafés overlooking the turquoise harbour – so different from the turn of the 20th century, when it was Martinique’s commercial hub and cultural epicentre. That all ended on the morning of May 8, 1902, when, in an instant, Saint-Pierre was transformed into the Pompeii of the Antilles. Mount Pelée violently erupted, spewing forth scalding toxic gases, ashes and a volcanic bomb on the uncomprehending population. In just two minutes the mountain snuffed out the lives of Saint-Pierre’s entire population of some 30,000 people – all except one. The death toll was essentially double the estimated 16,000 souls buried at Pompeii.

Who lived? He was a prisoner named Cyparis who had the good fortune to be in jail and protected from the blast and hot gases by the thick walls and the well-sealed door of his cell. He would later parlay that good fortune into a gig with the Barnum & Bailey circus, which travelled the country to display Cyparis’ burns, while a carnival barker embellished his story for the benefit of the holiday crowds.

Some ruins have been preserved as a morbid memorial. The most prominent is the remains of the 800-seat theatre with pillared portico and grand staircase that still overlooks Saint-Pierre harbour. It was built to bring plays by the likes of Molière and Voltaire to the island, and was without doubt the finest theatre in the Caribbean. Oddly, such a splendid building was right next door to the jail where the unfortunate Cyparis bided his time. Perhaps this was fortuitous – the theatre’s huge bulk may have provided his cell with additional protection. Whatever the case, just a few paces down Avenue Victor-Hugo is the bunker-like Volcano Museum that houses grim pictures of Saint-Pierre’s desolation and the shards from 30,000 shattered lives.

La Domaine de la Pagerie, the plantation where Joséphine once lived. Photo: Ken Harbinson

But in Joséphine’s time it was the plantation, not Saint-Pierre, that was at the centre of life. For a slave living on it, and wielding a machete all day long to slice down acres of the master’s sugar cane, the plantation was the only life he knew. His grim existence is depicted by the bamboo and thatch hovels of La Savane des Esclaves outdoor museum, where families slept on bare floors, washed and drank out of the same muddy pond and tended to their few goats and chickens. On Joséphine’s plantation some 200 slaves lived like this. Moreover, this life was not ancient history – a gnarled old-timer who helped build this museum assured me it represents the life he lived while growing up.

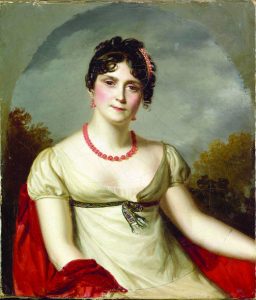

Joséphine, painted by Firmin Massot

The ruins of Joséphine’s tidy compound, just outside the village of Trois-Îlets, is called the Domaine de la Pagerie. It reflects the flipside of plantation life. The walls of the sugar-processing building where the family found refuge after the 1766 hurricane still stand, but the remaining compound is either reconstructed or, in the case of the manor house, mere foundational remains. The former kitchen is now a small museum of pictures and mementos of Joséphine’s and Napoleon’s lives, where a guide will tell you the details of her extraordinary rise to become Empress of France. All of this is set atop a grassy hill to catch the Caribbean breezes. (If you need a break, a nice golf course now occupies some of the plantation’s rolling landscape.)

Joséphine’s father, Joseph Tascher, was one of the less successful sugar magnates on Martinique. He apparently spent excess time enjoying city life in Fort-de-France. By contrast, Tascher’s relatives, the Dubuc family, who lived near the end of the spectacular Caravelle Peninsula, represented serious wealth and were paragons of Creole society, dealing in both sugar and the slave trade. Monsieur Dubuc is the one credited for negotiating with England to assume temporary control over Martinique during the Terror of the French Revolution, thus saving the island from the guillotine. Their success is duly reflected in the extensive ruins of Château Dubuc, which boasts probably the most beautiful vistas on the island. This was the home of Aimée du Buc de Rivéry before she disappeared into the world of Islam.

On an island dedicated to sugar cane, can a rum distillery be far behind? Of course not. In Martinique’s case there are four, with the result that virtually all the island’s sugar crop now finds its way into bottles. Moreover, as one might guess, pride dictates that Martinique rhum is the finest, since it is distilled directly from the sugar cane rather than molasses, as used by lesser rums. After intensive taste-testing, I have no reason to quarrel with them on this point.

Sugar plant ruin on La Domaine de la Pagerie. Photo: Ken Harbinson

Surely the place that best captures the entire spectrum of plantation life on Martinique is Habitation Clément. This is where President George H.W. Bush met with France’s François Mitterrand to consider their response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, while presumably enjoying a refreshing rhum libation on the balcony of the elegant 18th-century Creole-style manor house. The house, kitchen, stables and outbuildings all sit on the crest of the hill while, below, the Clément distillery rumbles along and the tasting room offers the visitor samples to sip and take home. In 2016 a new Fondation Clément was opened to showcase modern works of art from Caribbean artists. The entire complex is on some 16 manicured acres where vegetation from around the globe is carefully labelled.

But I don’t think that rhum and sugar were Martinique’s most important exports. That was formidable women. I can think of no other sun-washed island that can match Martinique in this regard. Marie-Josèphe Rose Tascher de la Pagerie (now known as Joséphine) is only the most recognisable. She mothered two children, had her teeth rotted out by Martinique’s sugar, sported a long roster of lovers while still becoming the belle of Parisian society capable of captivating Napoleon, who was six years her junior. She clearly brought something special to the game of life. When she failed to produce an heir to the Empire, Napoleon moved on to another wife, and Joséphine gracefully retired to her Malmaison estate and her beloved rose gardens. In early life she was known simply as Rose, so perhaps the gardens were a symbolic return to her roots. Be that as it may, history records that perhaps the last word Napoleon uttered before his death was “Joséphine”.

Joséphine, wife of Napoleon and ‘Rose of

Martinique’, painted by François Gérard

Barbary Coast Pirates

During the years Joséphine was captivating Napoleon, her cousin, Aimée du Buc de Rivéry, was captured by Barbary Coast pirates under the Bey of Algiers as she was returning to Martinique from Europe. What happened to her then is a mix of fact and Arabian Nights fantasy. As legend goes, the Bey gave Aimée to the Ottoman sultan in Istanbul as an attractive addition to his harem. She was given the Arabic name of Naksidil and gave birth to Sultan Mahmud II, the great Ottoman reformer who opened Islam to the Western world. The legend continues that Aimée was angered that Napoleon dumped cousin Joséphine for another wife and so persuaded the Sultan to make peace with Russia. This peace meant that Russia could turn its full attention to defeating Napoleon, as happened at the gates of Moscow in 1814. If just a fraction of the legend is true, Aimée’s diplomatic skills rank her up with Talleyrand and Richelieu.

A portrait of Aimée du Buc de Rivéry, who was captured by pirates and sold into slavery – artist unknown

Decades before Rose and Aimée were born, there was Françoise d’Aubigné. She may have been the most consequential of our Martinique women. She was born in a prison, where her disgraced father was being held for both murder and being on the wrong side of some political dispute among the French elite. Rather than being executed, however, he was pardoned, and fled with his family to Martinique. Once there, Françoise and the family were reduced to scrounging and begging for eight long years as Françoise was growing up. Finally, they were able to return to Paris, where Françoise began the long, slow climb back up the social ladder to respectability. This culminated when she became governess to a brood of Louis XIV’s illegitimate children, which put her in direct contact with the King.

Françoise d’Aubigné Maintenon, Louis XIV’s uncrowned queen, was also born in Martinique

You can guess the rest. In a story reminiscent of Jane Eyre, she worked her way into the royal bedroom and in due course became the Sun King’s morganatic wife, with the title of the Marquise de Maintenon. For 30 years she was on the right-hand of the throne. Her influence with the King derived from rigid Catholic beliefs that were increasingly reflected Louis’ policies as he grew older – not necessarily for the good.

Queen Hortense of Holland gained that post by marrying Napoleon’s brother Louis, whom she soon came to hate. She was born in Paris to Joséphine and Alexandre de Beauharnais and quite probably never set foot on Martinique. Nevertheless, she has enough Creole blood for me to anoint her an honorary islander. Besides, she bookends her mother – a period that Karl Marx characterised as beginning in tragedy and ending in farce. At the start of the 19th century, Joséphine was present at the creation of the Bonaparte Age. Hortense mothered Napoleon III, her hapless son, who presided over its burial some 75 years later. In the interval, the idea of a royal house for France had been discredited in Paris and the dark days of slavery on Martinique ran their course.

Hortense de Beauharnais, daughter of Joséphine and Queen of Holland

Dawdling over my crisp glass of vin blanc at the La Marina restaurant, overlooking the harbour in Trois-Îlets, just one thing bothers me: “What ever possessed these women to leave Martinique?

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY