In the Footsteps of Jules Verne in Nantes

Chloe Govan reveals the remarkable adventures of world-famous novelist Jules Verne, whose literary ambitions first took shape in beguiling Nantes

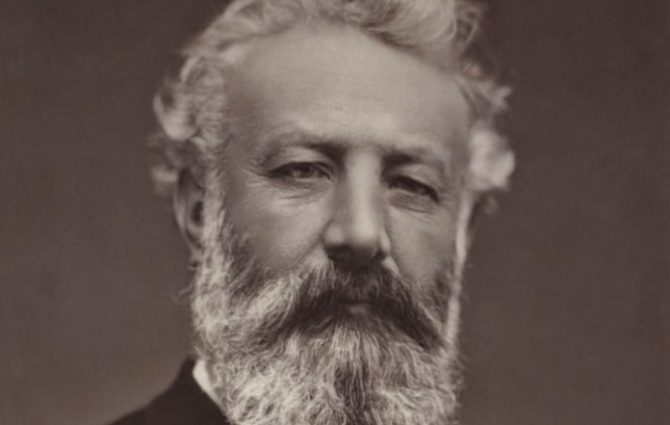

Say the name Jules Verne and most people will think immediately of Around the World in Eighty Days and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. But this master of adventure was also a poet and a playwright and one of France’s most prolific authors of all time, whose works have been translated more often than Shakespeare’s. Dubbed ‘the father of science fiction’, only Agatha Christie beats him to the title of most translated author in the world.

His life began in 1828 on L’île Feydeau in Nantes – then an idyllic little island set in the Loire river. He was educated at a local boarding school, where his teacher told romanticised tales of her sea-captain husband, who had gone missing on a voyage 30 years earlier. According to her, he was not dead, but had been shipwrecked on a paradisiacal desert island and one day – just like Robinson Crusoe – he would return. The six-year-old Verne listened avidly, wide-eyed with excitement. Perhaps this was the moment when his father’s ambitions for him to become a corporate lawyer melted away and the feverish imagination that would later transform him into an adventure writer was first sparked into action.

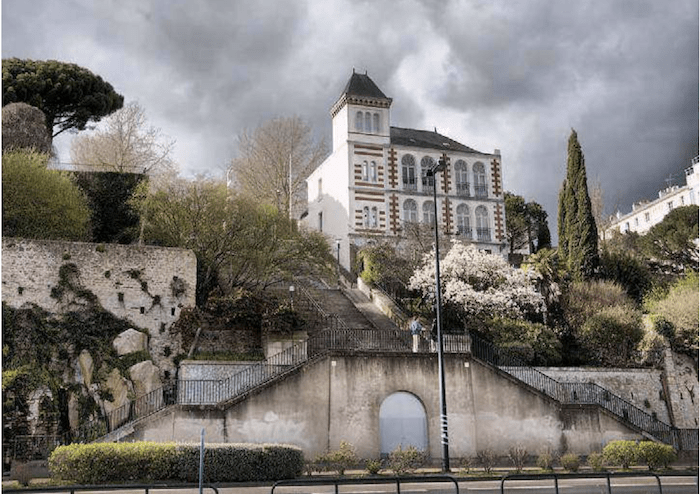

Musée Jules Verne in Nantes, where you can learn all about the life of this visionary writer and ‘father of science fiction’

Tall Tales

Within five years of hearing these stories, the young Verne was ready for his own adventure. Secretly gaining employment as a cabin boy, he managed to set sail for the West Indies before his parents noticed his absence. He had set his heart on discovering buried treasure and bringing back a coral necklace for the cousin he hoped one day to marry.

In modern times, it would be inconceivable for a child to gain employment without their parents’ permission, but back in the 1800s, no one batted an eyelid. The young adventurer sailed as far as Paimboeuf on the southern banks of the Loire before his distraught father caught up with him. He made his son promise never to travel again, unless in his imagination. Whether or not this legend was true, for a time, Verne substituted exploration of the real world with a passion for conjuring up fiction.

Later, he reluctantly attended a Parisian law school during the maelstrom of the 1848 French Revolution. Yet Verne, it seems, was oblivious to the political upheaval surrounding Napoleon’s election, instead losing himself in the works of Victor Hugo. Before long, he had read Notre-Dame de Paris so many times that he could recite by heart huge chunks at a time.

Don’t miss this mural celebrating Verne on the rue de l’Échelle. Photo © Pj44300

Despite passing his law exams with flying colours, he shunned all expectations that he would follow in his father’s footsteps. Even when an increasingly desperate Verne Senior offered his son ownership of the family’s law firm, he refused point-blank, simply quipping, “literature above all else”.

Verne produced a play with Alexandre Dumas’s son called Les Pailles Rompues, which appeared at Paris’s Théâtre Historique. To his father’s horror, he accepted the position of secretary at the theatre in return for a near non-existent salary and then, with 10 chums, launched the self-deprecating Onze Sans Femmes bachelors’ supper club. Even after his eventual marriage, Verne read, wrote and travelled voraciously.

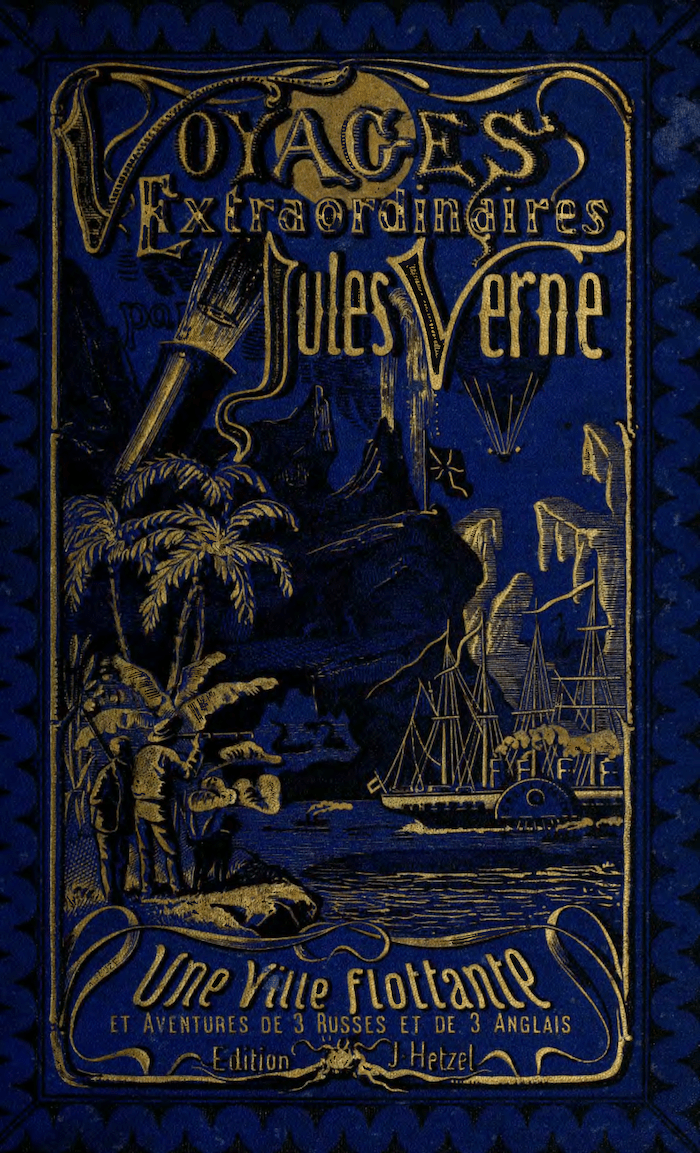

One of the 54 novels published in the Voyages Extraordinaires series. Photo © Wikimedia

The Big Break

In 1862, Verne had a literary breakthrough when Pierre-Jules Hetzel – the publisher of George Sand, Balzac and Victor Hugo – released his novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon. A series called the Voyages Extraordinaires followed, in which Verne revisited his fascination with adventures at sea, while outlining “all the geographical, geological, physical, and astronomical knowledge amassed by modern science” and “recounting the history of the universe”. Thanks to Verne’s imagination and rigorous academic research, he realised these lofty ambitions.

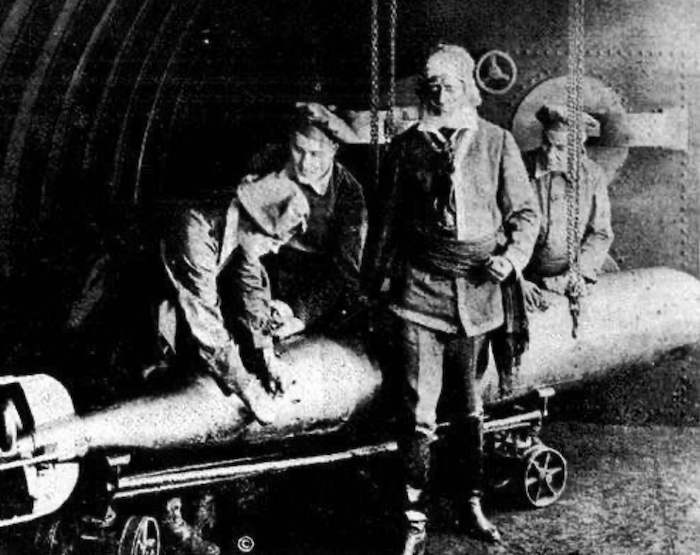

He wrote novels including Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, in which he accurately predicted the submarine before it had even been invented. He also relived childhood escape fantasies in A Captain at Fifteen, in which a teenage boy becomes the commander of a ship after its captain and crew are murdered. The ship’s conniving cook then lures him and a group of castaways off their route and into Africa, where he attempts to sell them into slavery.

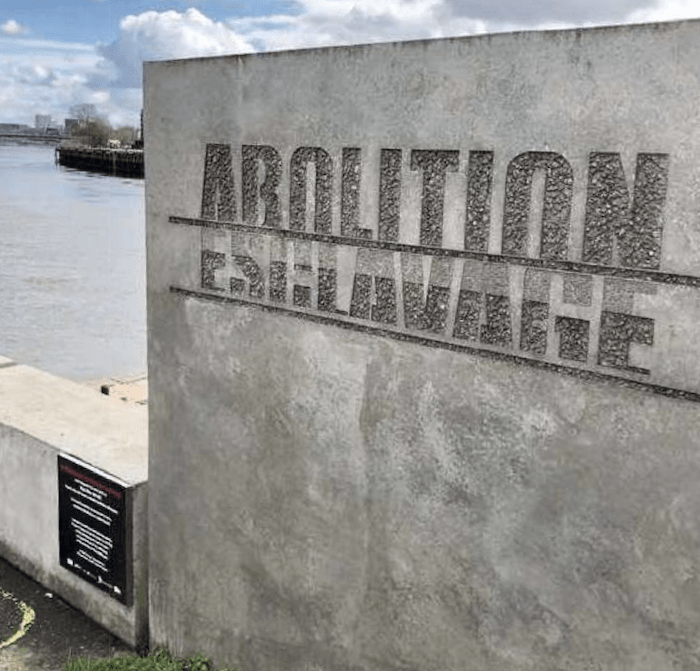

This theme is controversial for Verne. His wealthy ancestors were leading lights in the shipbuilding industry, and therefore indirectly complicit in slave trafficking. Nantes allegedly transported more than half a million people from African ‘slave forts’ to colonies in the Caribbean, to harvest sugar cane and cacao which would be transported back to France.

A 1916 film version of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Photo © Universal Film

In sentiment at least, Verne condemned slavery, although he clashed with Hetzel when the publisher argued that Captain Nemo should be made an enemy of the slave trade. Verne’s vision of Nemo was one of a vengeful scientist seeking to settle the score against the Russians who had slaughtered his family during the January Uprising. Yet profit-hungry Hetzel feared alienating his lucrative Russian audience. Hetzel also rejected Verne’s thriller The Mysterious Island, but disagreements did not mar his popularity. Verne was admired by many, including Jean-Paul Sartre, and legend has it that without Verne, novels like Bram Stoker’s Dracula might never have existed, as his novel The Carpathian Castle sparked Stoker’s imagination.

Following a brief political career and assassination attempt by his mentally unwell nephew, Verne died in Amiens in 1905 from complications caused by his diabetes.

The tales of his worldwide voyages and literary successes – not to mention a childhood that fuelled his love of the ocean – can be found in Nantes today at the museum dedicated to him. Those interested in following in Verne’s footsteps can also visit the Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery in Nantes, which documents a controversial past that both inspired the writer’s work and involved his ancestors. His former boarding school is now a restaurant, Bistro Régent, and there are historical associations aplenty elsewhere in the city for those adventurous enough to seek them out.

From France Today magazine

- the Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery is a reminder of Nantes’s dark past. Photo © OLGA MACH , JJHER, FRANÇOIS DE DIJON,

- Nantes’s monument to the author. Photo © OLGA MACH , JJHER, FRANÇOIS DE DIJON

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in author, history, inspiration

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *