Augustin Trébuchon: The Last French Soldier to Fall in the First World War

As centenary commemorations for the First World War draw to a close, Gillian Thornton discovers the story of the last French soldier to die

Over the past four years I’ve seen an awful lot of cemeteries and memorials while the world remembers a generation decimated by the First World War. I’ve walked among flower-fringed headstones and plain memorial crosses, and I’ve visited memorials and museums across northern France that have all touched my heart in their own way. But there is something intensely poignant about the white cross in this simple village churchyard in the French Ardennes. Here in Vrigne-Meuse, a small village near the departmental capital of Charleville-Mézières, lies the body of Augustin Trébuchon, the last French infantry soldier – or poilu – to die in the Great War.

Augustin Trébuchon’s headstone. Photo: Gillian Thornton

On November 10 and 11, 1918, the 163rd Infantry Division attacked across the Meuse on the orders of Marshal Foch in what was later described as “a useless battle”. The Germans were in retreat but still doggedly defending their positions, even as their generals were signing the Armistice conditions in Rethondes.

Somebody always had to be the last casualty, but it seems a cruel turn of fate that Augustin Trébuchon died just ten minutes before his friend Octave Delaluque announced the ceasefire on his bugle. And what makes it worse still is that Trébuchon was simply carrying a message to the front line when he was felled by a bullet.

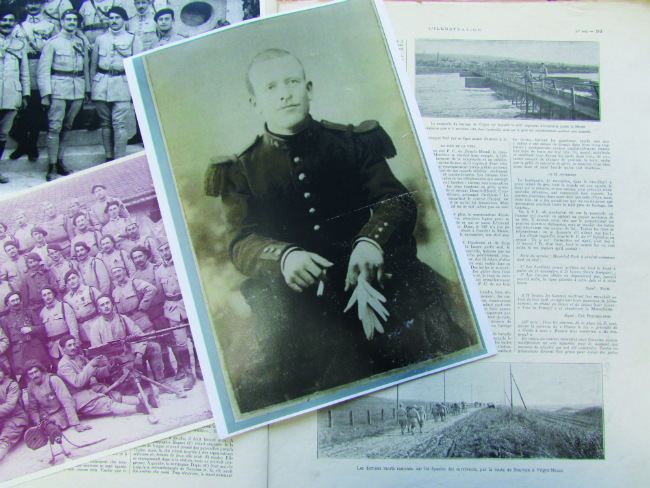

Photographs from the time are kept at the Mairie. Credit: Collection Vrigne-Meuse

Trébuchon’s story has only emerged in recent years, thanks to research by local enthusiasts into the last battle fought on their now peaceful doorstep. Suddenly Augustin became something of a local hero, a tangible link with the past for school children studying the Great War. But this year on Armistice Day, this ordinary Frenchman who led an otherwise normal life will achieve national recognition as a symbol of pride in a lost generation.

On November 11, Vrigne-Meuse will stage a ceremonial parade to bring high-profile guests from both France and Germany to this quiet village of just 300 inhabitants. Wreaths will be laid, military honours presented and tributes given. But the soldiers this time will be friendly, the atmosphere one of reconciliation rather than war. So, as Vrigne-Meuse prepared for its big Remembrance Day, I was curious to walk in the bootsteps of Augustin Trébuchon.

An orientation panel on the hill explains how the battle unfolded. Photo: Gillian Thornton

There is no equivalent site in Britain to the tiny war cemetery tucked into a corner of this village churchyard. The last British soldier to die in the war, George Edwin Ellison, rests at Mons in Belgium, not on his home soil.

“The bodies of many French soldiers were repatriated to their local cemeteries during the 1920s,” says Jean-Christophe Chanot, mayor of Vrigne-Meuse, as he welcomes me to the modest Town Hall. “But Trébuchon’s body was never claimed. We don’t think he ever married or had children. We have just one photo, given by his niece, Augusta Trébuchon, in the 1990s to Georges Dommelier, the former mayor who made Augustin’s story public. The number of his regiment, 142, is clearly visible on his collar and the pose in the photo leads us to believe that it was taken by a photographer in Toulouse.”

Jean-Christophe Chanot, mayor of Vrigne-Meuse. Photo: Gillian Thornton

One of six siblings, with two older brothers and three younger sisters, Augustin was born in the rural département of Lozère on May 30, 1878, the son of a shepherd. Augustin’s father died when he was just eight; his mother six years later, after which the children were brought up by an aunt. At the age of 12, Augustin left school and became a shepherd. Beyond that, we know nothing until August 1914 when, at the age of 36, he enlisted in the French army.

Trébuchon fought in the Marne, at Verdun, Artois and the Somme. Wounded twice, he received citations for his calm and exemplary attitude. Then on November 8, 1918, he was posted to Ardennes along with 700 men from the 415th Infantry Regiment of the 163rd Division. His job: Agent de Liaison.

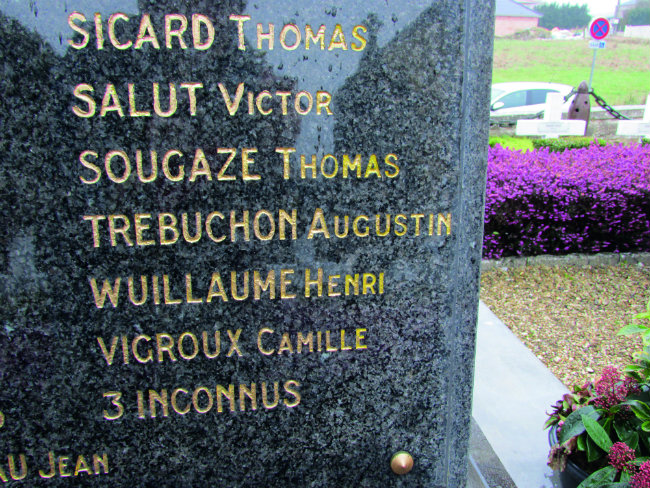

The memorial in the churchyard to the fallen of Vrigne-Meuse. Photo: Gillian Thornton

The ceasefire was scheduled for the 11th hour of the 11th month, and with less than 15 minutes to the end of hostilities, Trébuchon was sent to the front line with his message. It did not contain military orders but the welcome news that the mobile canteen would open at 11.30. The fighting would be over and soup would be served. But Trébuchon’s war was to end ten minutes early when he took a sniper’s bullet.

“We don’t know the exact circumstances of his death, but we do have an account written in the early 1980s by a local man,” says Chanot as we walk through the quiet streets to the spot where Trébuchon’s simple white cross looks out across fields towards the Meuse. The tiny war cemetery is flanked by box bushes, purple heather and ‘fence posts’ made from replica shells.

Trébuchon’s name on the memorial in the churchyard. Photo: Gillian Thornton

“André Gazareth found Trébuchon’s body along the railway line near the dam where French troops would cross the river. Even as an old man, Gazareth remembered the time of day and the fact that Trébuchon’s body was still warm.”

POLITICAL PROPAGANDA

But something doesn’t quite stack up. According to the simple inscription on the cross, Trébuchon and his comrades all died on Sunday 10th, not Monday 11th. The reason could be either political or practical.

“It wasn’t good propaganda to admit that so many soldiers died on the last morning of the war,” says Chanot. “So some people believe that the date was changed to avoid political scandal. Others think it was done to make sure that families received war pensions for loved ones lost during the fighting.

Photographic portrait of the fallen soldier. Credit: Collection Vrigne-Meuse

“Thirty-seven soldiers from the 415th Infantry Regiment died here that day. The bodies were gathered up from the woods and farmland that afternoon and the next day, and were taken to the church. Then, on the 13th, they were buried with full military honours. After the war, some of the bodies were moved by their families; their 18 comrades remain here.” Among many precious historical objects at the Mairie are black and white photos showing groups of soldiers, including bugler Delaluque, and four photographs of individuals who fell on the last day of the war, including Trébuchon. Chanot also shows me a copy of L’Illustration, a news magazine from 1920, which carries photos of the footbridge across the dam and stretcher-bearers taking bodies back to Vrigne-Meuse. One of them may well be Trébuchon.

The men are gone but their deeds live on. The main street has been named after the 415th Regiment, and on November 11, 2008, this quiet community also inaugurated rue Augustin Trébuchon. A 2km Trébuchon Trail was launched in April this year, ready for the centenary. The route begins at the entrance to the village in the newly-designed Esplanade, where a statue symbolising reconciliation and peace will be unveiled on October 14. The spirit of moving on is very important to an area that has suffered three periods of devastating loss of life: first in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and then in two World Wars.

The monument to the 163rd Division stands over the battlefield. Photo: Gillian Thornton

GLEAMING MONUMENT

The trail leads to Trébuchon’s grave in the churchyard, then up to the ridge known as the Signal de l’Épine Cote 249. Here, a gleaming white monument looks down on the last battlefield. Inaugurated in 1920, it honours the 163rd Division – even though most of the dead were from just one of its regiments – and carries a quotation from Jean Cocteau (after Tacitus): “Le vrai tombeau des morts c’est le coeur des vivants.” “The real tomb of the dead is the hearts of the living.”

Below the monument, an orientation panel explains how the battle unfolded. And as I stand there in the spring sunshine, looking down over peaceful farmland and water meadows, it’s a strange feeling to think that this is where four years of human carnage finally came to an end. And that the very last man to die perished for a bowl of soup.

VRIGNE-MEUSE ESSENTIALS

GETTING THERE

BY BOAT: Gillian crossed the Channel from Dover to Calais with DFDS (www.dfds.co.uk). Prices start from £39 each way for a car with up to 9 people; premium lounge upgrade, £12 per person.

BY ROAD: To reach Vrigne-Meuse, after Charleville-Mézières, leave the A34 motorway at Exit 6, then follow the D105 south.

USEFUL WEBSITES

For tourist information on Ardennes, visit www.ardennes.com

Inside the Museum of War and Peace in Ardennes. © CARL HOCQUART

MUSEUM OF WAR AND PEACE

January 2018 saw the opening of the Musée Guerre et Paix at Novion-Porcien in Ardennes, housed in a brand-new building and featuring 150 uniforms, 50 machines and a huge collection of artefacts from the three major conflicts fought in Ardennes.

And, of course, the story of Augustin Trébuchon features prominently. Or something like it. In the style of a French comic book, or bande dessinée, a film has been created by writer Kris (Christophe Goret) and illustrator Maël (Martin Leclerc) that is inspired by the story of the shepherd from Lozère.

A young soldier, called simply Augustin, dies from a bullet in the last minutes of the war while crossing the dam with his friend, Octave Delaluque. This much is based in fact. The rest, however, is fiction, designed to bring the past alive for a new generation, to emphasise the futility of war, and to show the effect that the Great War had on the women left behind.

Le Musée Guerre et Paix en Ardennes remembers the Franco-Prussian War and two World Wars. © CARL HOCQUART

The story involves a romance, a baby, and three generations of Augustin’s family – though no record exists of Augustin Trébuchon getting married or having children. There’s hope for the future as the fictionalised great-granddaughter meets a young German whose great-grandfather… Well, I won’t spoil it.

“I left out Augustin’s surname in order to put him on a level with all the victims of the war, and I created a family for him to represent all the families in mourning because of the conflict,” explains writer Kris. “The war in Ardennes effectively lasted 75 years, from 1870 to 1945, but Europe has maintained peace for 73 years now and I felt it was important to include a young German in the story.”

So while the story may not be true to Trébuchon, this clever short film is effective in making the Great War relevant to a modern audience, and fostering that all-important spirit of reconciliation that pervades Vrigne-Meuse. And I like to think that if Augustin could see it, he might be quietly pleased – a positive end to what he and his comrades gave their lives for.

For details on the museum, visit www.guerreetpaix.fr. Comic book fans can find the comic book by Kris and Maël, Notre Mère de la Guerre, at www.bedetheque.com

From France Today magazine

Le Musée Guerre et Paix en Ardennes. Photo: Gillian Thornton

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in first world war, WWI

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY