Poet Stéphane Mallarmé and his Influence on the Impressionists

Stéphane Mallarmé’s poetry is not the easiest to access, but his home at Valvins couldn’t be more welcoming, and the garden at the back is pure joy. It stands right on the banks of the Seine, in the commune of Vulaines-sur-Seine, in the department of Seine-et-Marne, and coming here is like stepping into one of the homes of the Impressionist circle, several of whom were his friends – Edouard Manet first and foremost, whose portrait of Mallarmé hangs at the Musée d’Orsay. There also exists a portrait of him by Renoir, which is now kept in Versailles, and a photo of Renoir and Mallarmé taken by Degas. Victor Hugo called him “notre cher poète impressioniste”, although he was really dedicated to the Symbolist movement, to seeking to “wrap the idea in an emotional form”, in reaction to the Naturalism promoted by the likes of Émile Zola.

Edouard_Manet’s portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé. 1876. Musée d’Orsay

Portrait of Mallarmé by Gauguin. Photo: Yvan Bourhis/ Conseil Départemental 77

A Country Retreat

It was Manet who urged Mallarmé to seek a country retreat, “to forget everything”. The edge of the forest of Fontainebleau was popular in the 19th century – heralded by the Barbizon painters, then by Sisley and Debussy, to name but a few. Mallarmé appears to have discovered Valvins in 1874, as an 18th-century coaching inn that had been converted into a farm. That summer he stayed here for the first time, crammed into two rented rooms upstairs with his wife, Marie Gerhard – a German governess seven years his elder – his daughter, Geneviève, and son, Anatole. That’s all he could afford on the modest salary of a teacher of English – even one at the prestigious Lycée Condorcet by the Gare Saint-Lazare.

Mallarmé et Renoir, photo by Degas. Credit: Yvan Bourhis/ Conseil Départemental 77

He developed friendships in the surrounding area: the painter Odilon Redon in Samois, across the Seine, and the writer, critic and editor Edouard Dujardin at the Villa Bella in the Haut-de-Changis. The three shared an affinity for Symbolism and an interest in Wagner. Dujardin was the founder of La Revue wagnérienne, to which Mallarmé contributed an essay, Richard Wagner, rêverie d’un poète français, and Redon a litho of Brünnehilde, a print of which he offered Mallarmé. It hangs in the “ladies’ bedroom” (la chambre de Mesdames).

Dujardin was also the founder of the Friends of Mallarmé Society and the Mallarmé Academy, to which he was elected President. A famous dandy too, he features in top hat and monocle in Toulouse-Lautrec’s iconic poster Le Divan japonais.

The garden at the Musée Mallarmé. Photo: Yvan Bourhis/ Conseil Départemental 77

A Marvellous Listener

The Natansons stayed even closer, round the corner at La Grangette. Thadée Natanson, the editor of La Revue blanche, was married to Misia, an accomplished pianist and legendary muse of the Paris art scene – it was to her that Ravel dedicated his Waltz. Mallarmé dined with them almost every night, arriving in clogs which he would take off in the hall, a red lantern in one hand, a bottle of top-class red wine in the other. “In exchange for his fairytales, I played him some music,” Misia reported. “Never did I have such a marvellous listener.”

Mallarmé also liked to have his friends come to visit, urging them to “interrupt him” in his “little house” – Manet, his brother, Eugène, his sister-in-law, Berthe Morisot, and their daughter, Julie. Orphaned from both parents by the age of 16, Julie moved to live with her cousins, “les petites Gobillard”, Paule and Jeannie. Mallarmé became her guardian, always happy to host “the flying squadron”, as he fondly called the three girls.

Façade of the Musée Mallarmé. Photo: Yvan Bourhis/ Conseil Départemental 77

The American painter James McNeill Whistler was another guest, as was the poet Paul Valéry, who would stay the night in the “pink parlour” around the spiral staircase downstairs, adjoining Mallarmé’s library. This was after Mallarmé had retired, in 1895, and rented additional rooms. Relieved from his teaching obligations, which he never enjoyed, he stayed here on his own for six months at a stretch – a short-lived pleasure, however, as he died here in 1898, aged only 56. He was not to attend Jeannie and Paul Valéry’s wedding, in 1900, nor to give away Geneviève to Edmond Bonniot, in 1901.

The dining room. Photo: Lucia Guanaes/ Musée Stéphane Mallarmé

A great admirer of his late father-in-law, Edmond supported his wife’s project to keep her father’s memory alive at Valvins. In 1902 they purchased the house and transferred here Mallarmé’s memorabilia from his Parisian apartment at 89 rue de Rome. The “Louis XVI” table (a copy, obviously) in the dining room is the one where his literary circle gathered on Tuesday evenings – “Les Mardistes” as they were nicknamed: which came to include Whistler, Valéry, Debussy, Oscar Wilde, André Gide and many others. The tobacco jar in the middle of the table is the one they would dip into during those smoke-filled evenings. The Japanese cabinet also came from the Rue de Rome. For years Mallarmé kept in its multiple little drawers his notes for his Great Work, his most ambitious but ultimately aborted project. On his death bed, he asked his daughter to destroy them.

Like many estates, Valvins passed on to Mallarmé’s indirect descendants and would almost certainly have been dispersed, had the local authorities of the Seine-et-Marne department not purchased it, in 1985, to secure the poet’s legacy. After extensive alterations and refurbishment, the museum opened in 1992, offering the visitor a journey through both the life of Mallarmé and his poetry. With that in mind, the first floor was restored as much as possible to how it was at the end of his life, reproducing, for example, the exact shade of green chosen by Marie and Geneviève for the bedroom they moved into in 1896.

interior of the

house, recreated to be as Mallarmé

left it. Photo: Yvan Bourhis/ Conseil Départemental77

Cabinet japonais. Photo: Yvan Bourhis/ Conseil Départemental

His Middle-Class World

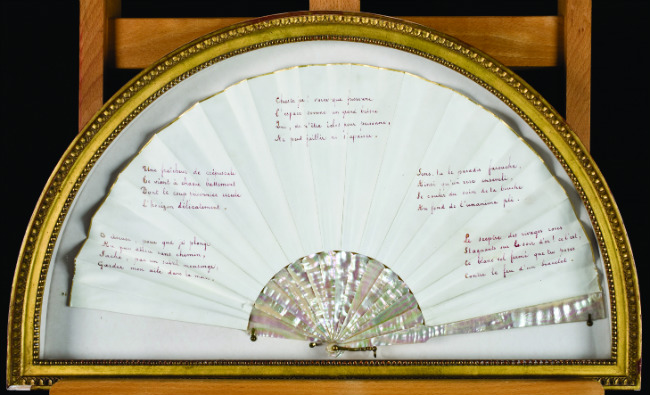

Each display has a story to tell. Some inspired a poem: Frisson d’hiver (Winter Shiver), for example, inspired by the 18th-century Dresden porcelain clock, a gift to his wife early on in their marriage. Their relationship was initially frowned upon by his middle-class world, though did gradually come to be accepted after their marriage. Mallarmé was very fond of the clock and took special care to set it off on the chimney mantelpiece, where it still stands. Another gift on display, to his daughter, is the fan with the beautifully hand-written poem by Mallarmé. It is one of his Vers de circonstance (Occasional Poems) he liked to offer friends and family on special occasions, like New Year.

Fan with poem by Mallarmé. Photo: Yvan Bourhis/ Conseil Départemental 77

The chequered shawl on the rocking chair is the one featured round Mallarmé’s shoulders in Paul Nadar’s photo. (Paul was the son of the better-known Félix, though a photographer in his own right). The shawl was a gift from his very special friend, (perhaps more), Méry Laurent, who was also the model and mistress of Manet. She is the woman behind the counter in Manet’s Un bar aux Folies Bergère. Gauguin’s La Bûche, a wooden sculpture in the shape of a log, is a homage to Mallarmé’s L’Après-midi d’un faune, famously put to music by Debussy and later choreographed and danced by Nijinsky. It was a thank-you gift to Mallarmé, who helped Gauguin raise the money for his journey to Tahiti. The piano, too, was a gift, from his friend and fellow poet Théodore de Banville. It is unclear whether Geneviève played it, but it seems that Ravel did, on the frequent occasions that he came over from La Grangette to visit Misia.

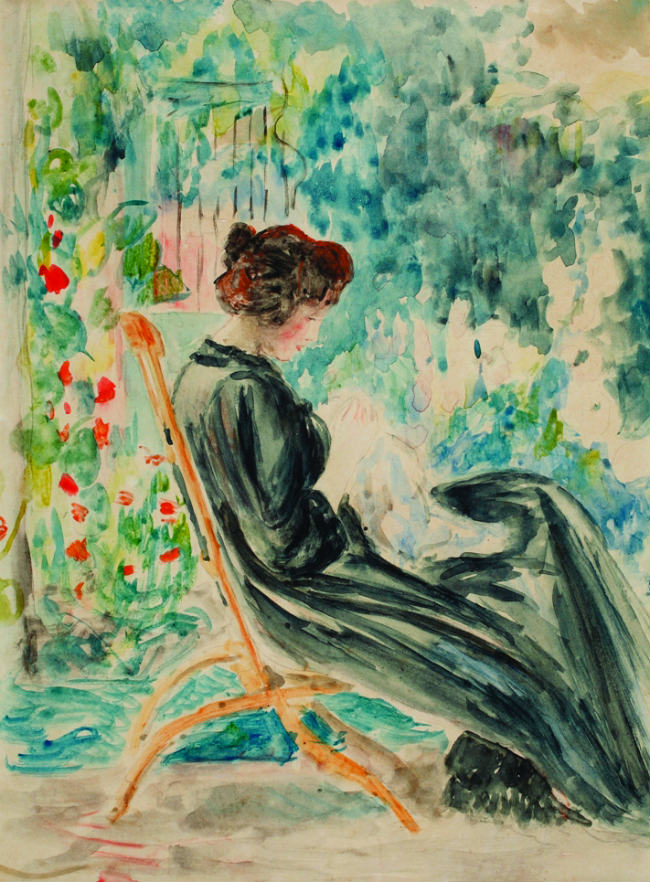

Daughter, Geneviève, in the garden by Julie Manet. Photo: Yvan Bourhis/ Conseil Départemental 77

Sad and Happy Moments

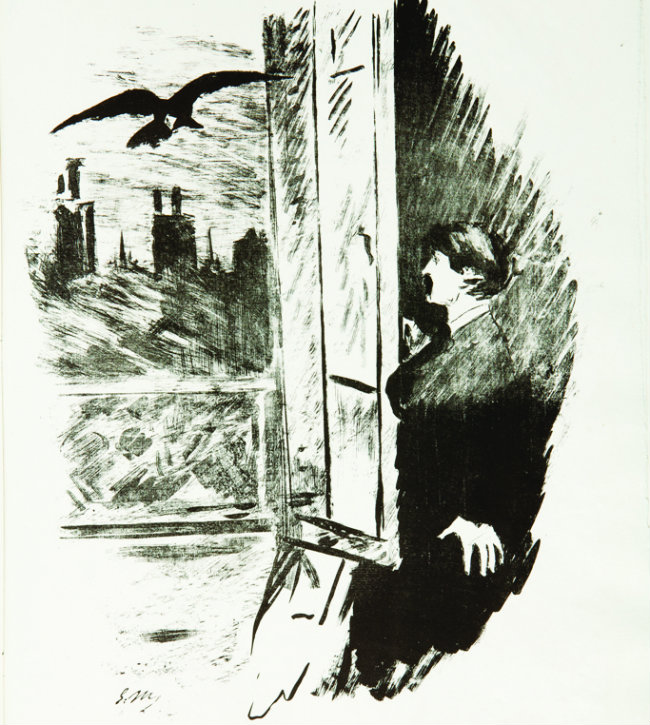

The child in the portrait in Mallarmé’s room is Anatole, who died at the age of eight. This caused a sorrow that never healed, one expressed in the poem Pour un tombeau d’Anatole. Anatole is buried in the nearby graveyard of Samoreau, like the rest of the family, and Misia too. There were many happy moments too, of intellectual pursuits, gardening and boating. His English library contains works by Shakespeare, Byron, Shelley, the Brontës, a whole shelf of his much admired Edgar Allan Poe, for whose sake Mallarmé learnt English and then proceeded to translate much of his verse – The Raven (Le Corbeau) notably, which was published in 1875 with illustrations by Manet.

Manet’s “le corbeau.” Photo: Yvan Bourhis/ Conseil Départemental 77

Mallarmé loved gardening. The garden at Valvins was typical of those along the Seine at the time, and has been recreated as it was, thanks to his correspondence and old photos. He is even present in the outside toilets, where he engraved on one of its walls a quatrain from one of his Casual Poems, “You who are relieving your guts / You may in this dark shelter / Sing or smoke your pipe / Without touching the wall with your fingers.”

Sailing on the river was his other passion. His boat, un canot simply named SM, was made in Honfleur but no longer exists. The scale model on display was also made thanks to Mallarmé’s correspondence and old photos. He was the capitaine on board, as Manet fondly dubbed him, taking painstaking care of the boat. Several poems pay homage to the “flowing ‘yole’, forever literary”, as it was described by Paul Valéry, though yoles are narrow boats propelled by oars, like those in Caillebotte’s painting; Mallarmé’s boat had no oars, but rather a big, white sail like “the page on which one writes”. One may assume that the word ‘yole’ sounded melodious to ears that loved music.

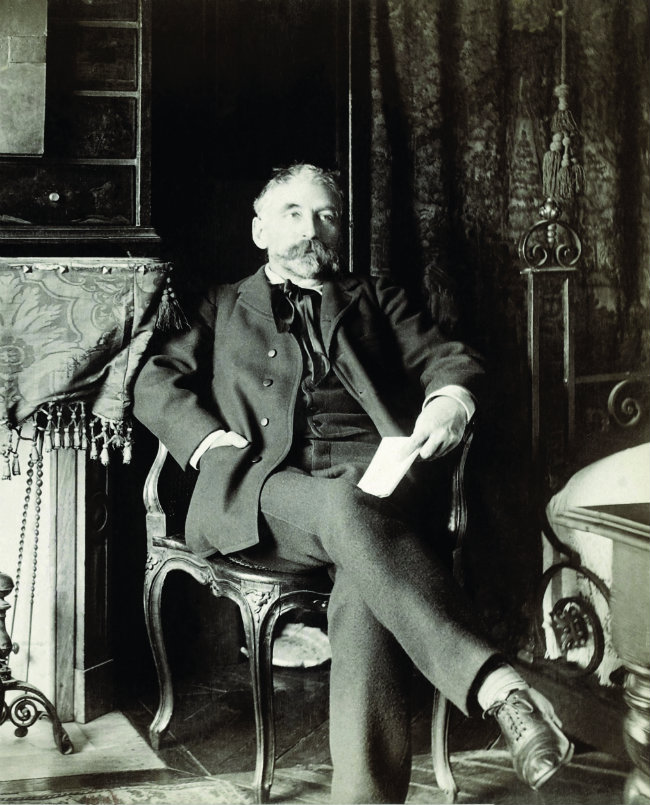

Stéphane Mallarmé by Dornac. Photo: BNF/ Gallica

ESSENTIALS

Musée Départemental Stéphane Mallarmé: 4 promenade Stéphane Mallarmé, 77870 Vulaines-sur-Seine. Tel: +33 01 64 23 73 27. Email: [email protected]. Open daily except Tuesdays, May 1st, and December 24th to January 1st. 10am-12.30pm and 2pm-5.30pm (6pm in July and August)

From France Today magazine

Some images are supplied with the kind permission of the Musée Départemental Stéphane Mallarmé on behalf of the Conseil Départemental de Seine-et-Marne.

The Dresden clock, a gift from Mallarmé to his wife. Photo: Yvan Bourhis/ Conseil Départemental 77

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY