La Fée Verte: The Revival of Absinthe

Alcohol and firearms rarely mix well. For instance, in August 1905 they produced a particularly lethal cocktail when Franco-Swiss peasant Jean Lanfray downed two glasses of absinthe, picked up his old army rifle and promptly dispatched his entire family. The authorities immediately blamed Lanfray’s actions on ‘La Fée Verte’ (The Green Fairy), as absinthe was known back then. The fact that Lanfray was a raging alcoholic who had consumed enough wine and brandy to sink a battleship just the day before was by-the-by.

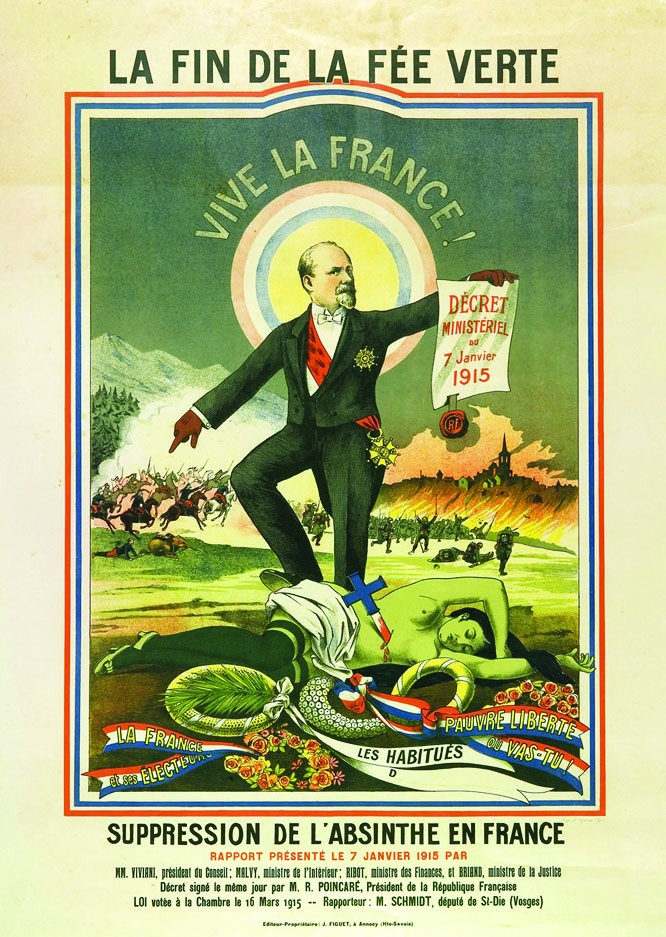

In turn-of-the-century Switzerland, absinthe was seen as the cause of all society’s ills. Lanfray was simply the catalyst that the authorities needed to implement an outright ban on the drink. Not long afterwards, France and several other nations followed suit.

Now, just under 100 years later, absinthe is back on the menu of French bars. In 2011 the government ban on the drink was overturned, which is good news for anyone who wants to ‘party like it’s 1899’.

One man who’s determined to party more than most is George Rowley, the owner of French absinthe brand La Fée. It was George who spearheaded the 1990s revival of absinthe and who helped overturn the century-old French ban. He now distils traditional absinthe in the Rhône-Alpes and Franche-Comté, and in the Swiss region of Neuchatel, selling wholesale to around 40 territories worldwide.

At his UK home, in Hertfordshire, from where he runs La Fée, George demonstrates the classic method of preparing absinthe. He sloshes a measure of the drink into a glass and then, suspending a white sugar lump on a perforated absinthe spoon, slowly drips iced water over it. Gradually, as the two liquids mix, greenish swirls (the infamous ‘green fairy’) appear. The final taste is hard to pin down: a mix of aniseed, fennel and slightly bitter herbs, albeit tempered by the sugar.

Younger absinthe drinkers tend to favour something known as the Bohemian method, a much more theatrical way of preparing the drink. This involves soaking a sugar cube in absinthe and setting fire to it before mixing it into the glass and knocking the whole concoction back like a shot. Watch out for your nostril hairs!

“We’re very optimistic,” says George, when asked if he believes that absinthe will once again become a staple French drink. “I can really sense it. The decision, I suppose, is with the next generation. But my feeling is the next generation are more likely to be involved with a drink like absinthe than with a drink like pastis.”

That’s a good point, as pastis first became popular as a replacement for absinthe after the French ban finally came into force, in 1915.

In certain sectors of 19th-century French society, absinthe was more prevalent than wine. It was mainly thanks to the French army, which supplied the drink to its troops in Algeria and Indo-China, in order to stave off malaria. Returning home, the troops found that they’d developed a penchant for the stuff and started ordering it in bars. Civilians followed suit and the green fairy quickly became so trendy that, by the 1860s, happy hour was called ‘l’heure verte’ (the green hour). By 1910 the French were consuming 36 million litres a year.

It was particularly popular with the working classes since (often adulterated) versions of the drink were cheaper than wine, but also with the bourgeoisie – whose wine supplies had been decimated by the phylloxera bug – and most infamously with bohemian artists and writers.

Manet, Rimbaud, de Maupassant, Toulouse-Lautrec, Verlaine, Baudelaire and Zola were all very fond of a tipple or three, often writing about or depicting the drink in their works. Van Gogh was supposedly the biggest absinthe guzzler of them all. Some even believe it was after a rather debauched absinthe session that he lopped off his ear.

During the Belle Époque, absinthe got some very bad press indeed. Its meteoric rise in popularity coincided with the growth of the pan-European temperance movement and by the start of the 20th century, absinthe was being firmly blamed for many of society’s ills.

Jad Adams, in his book Hideous Absinthe: A History of the Devil in a Bottle, wrote that, “Over mere decades, absinthe was transformed from the green fairy, muse of artists, hymned by poets, aperitif of the middle class, to the poison of the haggard working class, responsible for all the ills of industrialisation. A bitter green liqueur had become ‘the scourge’, ‘the plague’, ‘the enemy’, ‘the queen of poisons’, blamed for the near collapse of France in the first weeks of the Great War. Absinthe was accused of filling the asylums, of the murder of whole families, of leading to spontaneous human combustion in habitual users.”

The Thujone Question…

Science, however, proves that absinthe was an undeserving scapegoat. Distilled from anise, fennel and wormwood, it contains a substance called thujone. In massive quantities, thujone could turn a rhinocerous epileptic, which is perhaps why absinthe enjoys a legendary reputation as a mind-altering drug, rather than as a simple (but very strong) drink. The artists of the Belle Époque certainly enjoyed perpetuating this myth. However, absinthe contains only tiny amounts of thujone, barely enough to fell a mouse. It’s the alcohol content, which is sometimes more than 80 per cent proof, that you actually need to worry about, rather than the thujone.

Nevertheless, some drinkers claim to have experienced what they described as lucid drunkenness after too many absinthes. Oscar Wilde, who was famously fond of the green fairy, reported that, “After the first glass you see things as you wish they were. After the second, you see things as they are not. Finally you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world.”

It’s this lucid drunkenness that’s perhaps the most intriguing aspect of absinthe. One place where the confirmation of the theory can be confirmed or disproved is Le Musée de l’Absinthe, which is situated in Auvers-sur-Oise, just north-west of Paris. The founder and director of the museum is Marie-Claude Delahaye, who’s arguably the world’s greatest expert on absinthe.

“Whenever I drink absinthe, it’s a really diluted version, so I can’t really tell you about lucid drunkenness,” she told us, rather disappointingly. “But I do know the herbs in the drink have a stimulating, exhilarating effect so that if you drink too much you have a sort of upbeat drunkenness.”

A Toast to the Future?

Marie-Claude is delighted that the French government has now overturned the absinthe ban. Several years ago, she joined forces with George Rowley and the Fédération Française des Spiritueux, to lobby the French government to this end. But she admits there were certain economic factors in their favour.

In 2005 the Swiss government overturned its century-old ban on absinthe and that country’s manufacturers of the drink quickly attempted to give their product what’s known as a ‘protected designation of origin’ status – a bit like the AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée) in France. French distillers, led by the mighty Pernod, realised they were potentially missing out on enormous global sales. The French government sympathised and so lifted the ban.

“There are now around 30 brands of absinthe being distilled in France,” Marie-Claude says. “Some of them are just niche regional products. Others, like Pernod, are huge distillers. At the moment there’s a lot of curiosity among consumers about the drink. Some people who come to my museum don’t even realise that it’s legal now.”

Ultimately, the future of the drink in France all hinges on its major manufacturer, Pernod. Marie-Claude has had several discussions with Pernod’s boss, César Giron.

“He came to my museum,” Marie-Claude says proudly. “He was very happy with the popularity of absinthe. He believes very strongly in the drink’s future.”

With Pernod’s backing, maybe the French will soon be partying again like it’s 1899.

DETAILS

Absinthe Today

Since 1898, Distilleries & Domaines de Provence have been making Provençal liqueurs and aperitifs in Forcalquier. Today, utilising a combination of artisanal distillation techniques and a high quality mixture of botanicals, including wormwood, they create a complete range of absinthe products, such as Grande Absente. For more information, visit www.distilleriesprovence.com

Shaken and Quite Blurred: Toulouse-Lautrec’s unfortunate love for absinthe

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was one of France’s most notorious artists. It’s safe to say that many of his finest paintings were created within the dizzy haze of absinthe. Some, like At Gennelle, Absinthe Drinker (1886), Van Gogh with Absinthe Glass (1887) or Monsieur Boileau au Café (1893) deal directly with the popular drink.

It was among the Bohemian artists of Montmartre that Lautrec first threw himself into the boozy lifestyle. Teased about his stunted physique, Lautrec gradually increased his intake of spirits – especially of absinthe – until he finally became quite the alcoholic.

Toulouse-Lautrec is credited with inventing a cocktail called the ‘Tremblement de Terre’ (‘Earthquake’), which featured equal parts absinthe and Cognac, shaken with ice. In Lautrec’s later life his alcoholism was so chronic that he reportedly kept vials of absinthe and other spirits in the top of his walking cane.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Absinthe

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *