Femmes Résistantes: World War II’s Unsung Warriors

Lest we forget, the brave and dauntless resistance fighters of the Second World War counted among them numerous women, from all walks of life. Jennifer Ladonne looks at some of their stories.

On a beautiful day in May 2015, President François Hollande, standing on the vast steps of Paris’s Pantheon, facing four caskets draped with the French Tricolore, paid homage to four heroes of the French Resistance on the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. A relatively unremarkable event but for the fact that two of the renowned resistance fighters about to join such historic figures as Voltaire and Zola in France’s famous monument “to great men” were, in fact, great women.

Before this day in 2015, only two other women had gained entry: the wife of a worthy great who insisted on her presence and Marie Curie, honoured in 1995.

President François Hollande outside the Pantheon in Paris in May 2015. Photo credit © Alamy

The two female honourees, Germaine Tillion and Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, both began their resistance work at Paris’s Musée de l’Homme. Tillion was already a noted anthropologist, and de Gaulle, niece of the famous general, was a university student infuriated by Marshal Pétain’s armistice with the Nazis in June 1940. In the course of their work, both women were captured and survived the horrors of Germany’s Ravensbrück concentration camp. Tillion escaped in 1945, and de Gaulle, having been kept alive only as a potential bargaining chip thanks to her illustrious name, was rescued in April 1945. Both women spent the rest of their long lives (Tillion died in 2008 at the age of 100 and de Gaulle-Anthonioz in 2002, aged 81) as committed activists and illustrious figures in French politics and letters.

Germaine Tillion, who was honoured at the Pantheon in 2015. Photo credit © MRN Photos

Hollande’s long overdue gesture both satisfied and disappointed French feminists and historians, who’d hoped to see four women distinguished that day. Many considered it meagre atonement for an omission that has yet to be rectified in either the history books or the public mind. In a movement that demanded anonymity by its very nature, women’s roles were the most anonymous of all. Yet their work pervaded every aspect of the resistance. Women willingly undertook any task offered to men no matter how perilous, from distributing clandestine newspapers and espionage to parachute drops and armed combat. At the same time, women performed all the roles of their traditional domain in service to the cause – caregivers, nurses, providers of food and shelter, seamstresses, secretaries – mundane tasks that would prove crucial to the resistance effort and that many men couldn’t – or wouldn’t – assume.

If caught, women resisters suffered the same fate as their male counterparts. Internment and concentration camps were filled with résistantes, who were subject to the same beatings, torture and execution as men, yet female resisters were much more vulnerable to having their children and loved ones held hostage, brutally beaten or murdered before their eyes to induce them to talk. Many resisters, both women and men, remarked after the war that women held up better under torture than men.

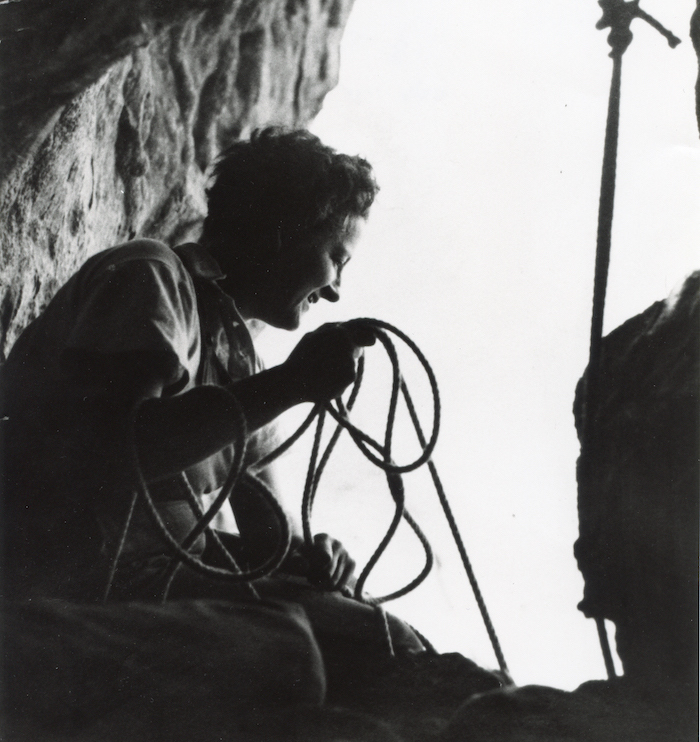

Women performed all kinds of tasks during the war. Photo credit © MRN Photos

Undercover Heroines

There are countless more French heroines than could ever be packed into the Pantheon. So why have they been largely overlooked or ignored? Sadly, for all the obvious reasons, but also because, as Margaret Collins Weitz observed while conducting dozens of personal interviews with resisters for her book Sisters in the Resistance: How Women Fought to Free France 1940-1945, no matter the danger, women did not see themselves as doing anything particularly “heroic” or even out of the ordinary.

Nor did many men see them that way, including those with ample evidence to the contrary. After the liberation, General de Gaulle, who’d spent the duration of the war leading his Free France resistance movement from the relative safety of London, issued a list of 1,038 resistance heroes; only six were women. De Gaulle, slow to recognise the many resistance movements that sprang up after Pétain’s Vichy collaboration, only grudgingly, and belatedly, admitted women to his own organisation at the urging of his French and British compatriots.

A mural of Germaine Tillion and Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz on the shutters of a bookshop in Paris’s 20th arrondissement. Photo credit © Alamy

But if De Gaulle was reluctant, other leaders were not. Georges Loustaunau-Lacau, a French major and intelligence officer who had anticipated both France’s military weakness in the face of Nazi aggression and Pétain’s capitulation, had the foresight to recruit Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, first in 1936 at his publishing house, then, after his arrest in 1941, as his replacement at the head of the spy network Alliance. The boldness of choosing a woman to lead one of the war’s most important spy networks cannot be overstated. But with a car, a pilot’s licence, a good job and a good pedigree, Fourcade was no ordinary woman. Shaped by an adventurous childhood spent in Shanghai, this chic Parisienne was also “born to privilege and known for her beauty and glamour”, recounts Lynne Olson in her real-life thriller, Madame Fourcade’s Secret War. Steely and quick-witted, the 32-year-old Fourcade was also a master of disguise, which came in handy on more than one occasion. Among her many hair-raising exploits, she survived a freezing night stuffed in a mail sack in a train freight car and escaped twice from the Gestapo, once asking permission from a priest to take the cyanide pills she carried before finding a way to squeeze her naked body out of a barred window.

As the head of Britain’s M16 noted, the average resistance fighter lasted six months in the field before being captured or killed. Fourcade lasted four years, and at Alliance’s high point commanded 3,000 active members. Under her leadership, Alliance provided the British and Allied forces with some of the war’s most crucial intelligence, including the location of a new Nazi superweapon, the V2 rocket, that might well have reversed the war’s outcome – thanks to a woman.

Fourcade’s agent Jeannie Rousseau, a pretty 20-year-old graduate from an elite university who was fluent in German, applied at the Nazi’s Brittany headquarters for the job of translator. The intelligence she gathered, due to the carelessness of Nazi officers disarmed by this charming, seemingly guileless blond, permitted the Allies to obliterate the German weapons site.

Women kept daily life going. Photo credit © Alamy

Though Fourcade was the sole female leader of a major resistance network, dozens more held positions of incalculable importance to the effort. Berty Albrecht, a co-founder and powerhouse behind the major clandestine organisation Combat, created and oversaw its social services section to provide much-needed support to the wives and children of captured agents, a blueprint that other clandestine groups readily copied. Due to extreme shortages of food, clothing, shoes, bicycles and the basic necessities of life, all requisitioned by the Nazis, Albrecht’s initiative proved vital, especially after the mass deportation of French men to Germany in the Vichy government’s compulsory forced labour program (STO), initiated in 1942. She also co-founded the journal Combat (whose contributors included Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus), which was edited by her friend Jacqueline Bernard until Bernard’s arrest in 1944. A tireless activist and feminist before the war, Albrecht was a champion of social causes even after her capture in 1942, drawing up a report on the shocking conditions of the French prison where she was being held. Married earlier in life to a banker in London, Albrecht joked while scrubbing prison toilets how she’d shared a dressmaker with the Queen.

Though Albrecht managed a daring escape with the help of her daughter, she was recaptured by the Gestapo five months later, in May 1943. To avoid the risk of divulging any of her vast covert knowledge under torture, she committed suicide.

Lucie and Raymond Aubrac. Photo credit © MRN Photos

Lucie Aubrac, another co-founder of a major resistance network, Libération-sud, with her husband Raymond Aubrac, and a founder of the underground journal Libération, was one of the rare women to bear arms, even while pregnant. Aubrac helped organise railroad sabotage attacks and carried out a daring armed rescue mission to free her husband, along with 15 other prisoners, from a Vichy jail.

Weitz points out that despite her bravery, Aubrac believed that, “the women who hid arms had a much more dangerous assignment than she did as leader of a hit squad… Attacks were rapid and soon over while the farm women spent months not knowing when the enemy might discover their arms caches. They had to live daily with that fear”. Aubrac survived the war, becoming the first woman to serve in the French parliament, appointed by de Gaulle in 1944 for her contribution to the cause.

- Women resisters detained by the Nazis at Romainville. Photo credit © MRN Photos

- Photo credit © MRN Photos

- Photo credit © MRN Photos

- Photo credit © MRN Photos

All Walks of Life

It is impossible to overstate the extreme danger to anyone who undertook even the smallest action to undermine the German war effort. In the occupied territories, Nazi soldiers and the Gestapo inflicted brutal punishments calculated to terrorise the French.

As Weitz recounts, one Madame Bourgeois was tied to a tree and shot in front of her daughter for “harassing” German soldiers requisitioning her home. Her daughter was forced to bury her mother herself, but not before leaving her corpse hanging for 24 hours. Meanwhile, Pétain’s forces ruthlessly patrolled the unoccupied south.

When the Nazis took the south of France in 1942, the Gestapo redoubled its efforts against the resistance, putting anyone who was working undercover in even greater peril.

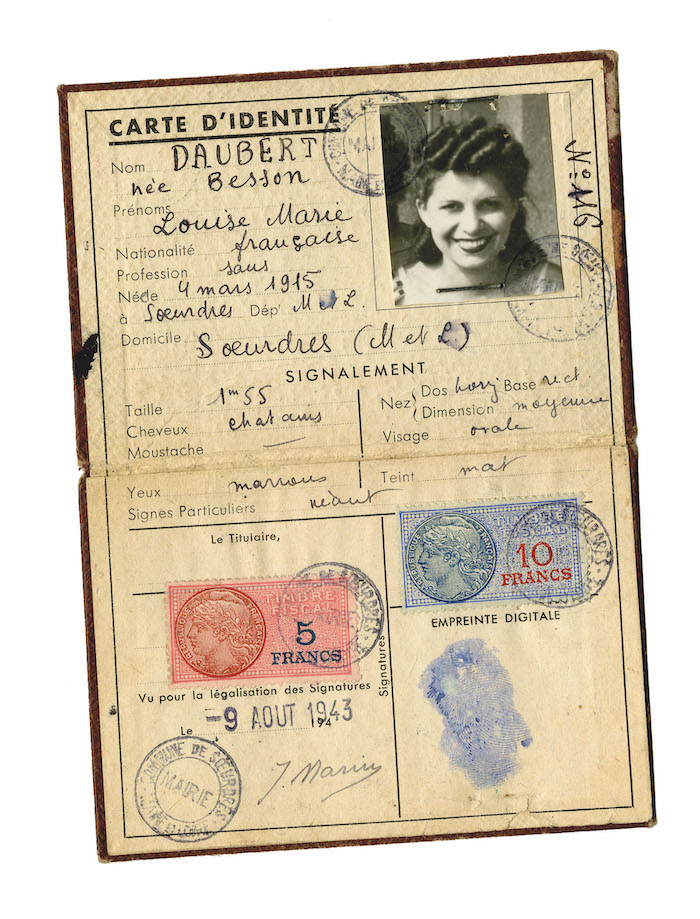

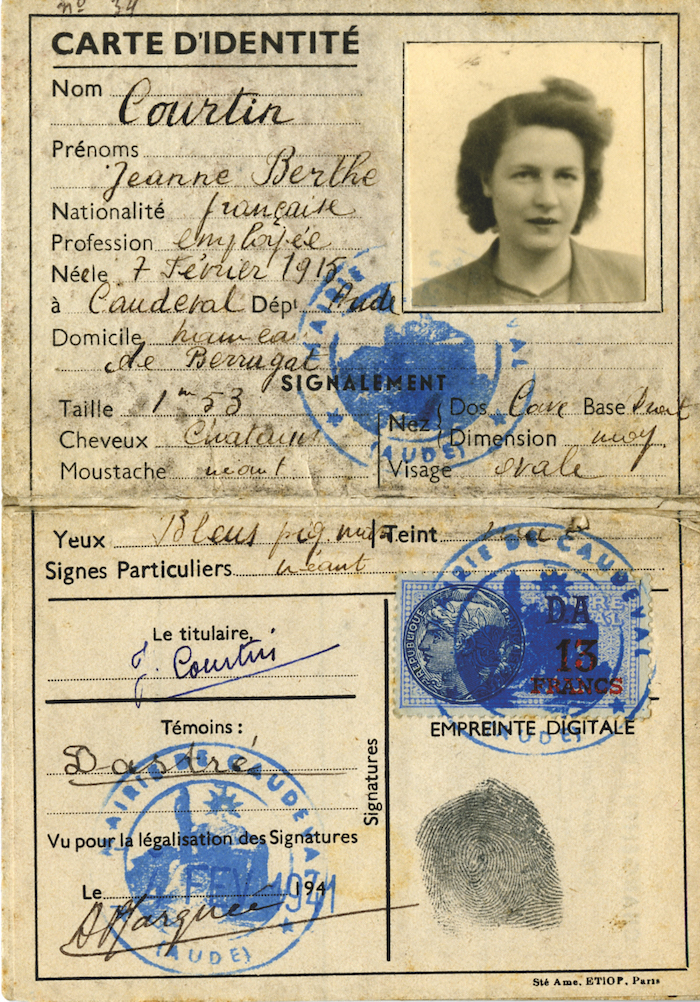

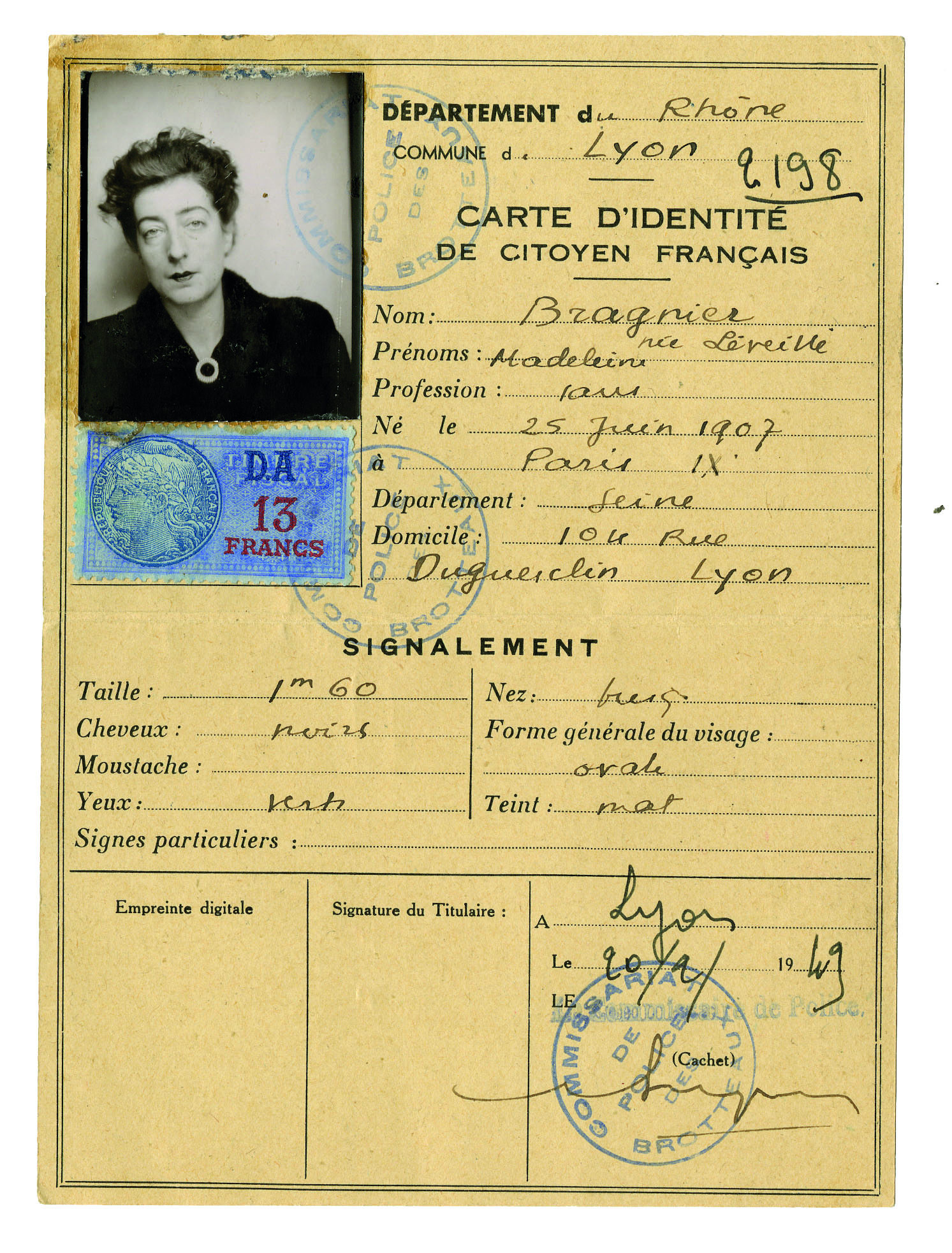

- Fake identity papers for Emma Levin, Yvette Semard, Madeleine Braun and Claudine Choma. Photo credit © MRN Photos

- Photo credit © MRN Photos

- Photo credit © MRN Photos

Women who participated in the resistance may have shared a certain independence, idealism or patriotism, but they defied easy categorisation. Resisters ranged from as young as 13 to as old as 89, came from all backgrounds and social spheres and performed countless services, big and small. For instance, one 84-year-old Parisienne offered her Bastille laundromat to a clandestine printing press, while an 89-year-old aunt of a résistante figured she had little to lose if she were caught sheltering marooned Allied aviators. Teachers and nurses organised underground networks to hide or smuggle Jews out of the country. Nuns harboured fugitives. Farm women shared what little food they could scrounge and hid Maquis guerrilla fighters. Students forged identity papers (and gave their own to young Jews) and cycled countless miles to deliver supplies and messages. Secretaries operated transmitters to send, code or decode messages, and diffused information ingeniously typed on lightweight silk and sewn into pocketbooks or hemlines.

In one instance, the illiterate housekeeper of a prominent resistance leader concealed his heavy transmitter in her apron while the Gestapo searched the house, almost certainly saving his life. He had no idea she even knew what a transmitter was.

Women finally got the vote in 1944. Photo credit © MRN Photos

French woman may have been denied the right to vote (that came in 1944) or even open a bank account, but they showed a remarkable ingenuity, courage and resilience in the face of their oppressors. As diverse a group as they were, French résistantes were united in their refusal to submit.

As Lynne Olsen eloquently concluded in her book: “A moral common denominator overrode all the differences: a refusal to be silenced and an iron determination to fight against the destruction of freedom and human dignity.

“In doing so, they, along with other members of the resistance, saved the soul and honour of France.” We might all take their timeless example to heart.

Interested to read more about other women involved in the French Resistance? Follow in the footsteps of Josephine Baker because when war came, she was ready to risk her life.

From France Today magazine

The war revolutionised day-to-day life for ordinary citizens. Photo credit © Alamy

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in French Resistance, Second World War, women in French history, WWII

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY