In the Footsteps of Ambroise Vollard

From humble beginnings on Réunion island, Ambroise Vollard became one of the most important art dealers France has ever seen, as Hazel Smith discovers.

At first glance, the dusty windows of the shop on rue Laffitte didn’t offer much of interest, but on closer inspection they revealed, perhaps, a small painting by Cézanne, Gauguin or Bonnard. By day, the shop was dark; at night, a flickering lamp revealed a dusty room with rolled canvases and pictures stacked floor to ceiling, and at its centre, seemingly asleep, Ambroise Vollard.

Hugely influential in the world of French art, Vollard was an art dealer whose influence straddled the 19th and 20th centuries. He represented a diverse range of artists, including Impressionists Renoir and Degas, Post-Impressionists Cézanne and Gauguin, and the avant-garde of the new century.

Paris art scene

Born in 1866 in the French colony of La Réunion, the island’s tropical surroundings accustomed Vollard’s eye to vivid colours and combinations. He collected butterflies, feathers, shells and shards of colourful pottery and as the eldest of ten children, he learned early on how to protect his possessions.

Vollard arrived in Paris aged 21. More interested in window-shopping amongst the Seine’s bouquinistes than in studying law, he found work as a gallery assistant at l’Union Artistique where he was faced with the cliché that ‘Impressionists don’t know how to draw’. Montmartre captivated Vollard and he spent his evenings at Le Chat Noir and Le Café du Tambourin. Living hand to mouth in his garret rooms, he began selling his own small art collection. With a trusting banker behind him, Vollard set up his own gallery in the heart of the Paris art world. In 1893, rue Laffitte was a place of pilgrimage for young painters. His first successful exhibition was in 1894, when he shrewdly convinced the widow of Édouard Manet to allow him to sell the artist’s drawings and unfinished works.

Ambroise Vollard_by Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Timeworn and tired of Impressionism, Renoir suggested instead that Vollard assist the talented Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne, whom Vollard found to be a reclusive, depressed man of middle age. He bought 150 canvases from the artist at a modest price, with the idea of selling them for substantially more. It’s said that the future of modern art began in 1895 when Vollard exhibited Cézanne’s vividly colourful works. Vollard believed that Cézanne was the greatest painter who had ever lived: trusting his eyes instead of relying on theory, Cézanne turned the tide from academic stagnation to freer paths. Vollard’s influence brought Cézanne lifelong recognition and financial success.

Vollard also invested in the works of Gauguin, a man he described as a “tall, arrogant, Oriental prince”. He agreed to regular purchases to secure the artist’s Tahitian lifestyle. To Gauguin’s irritation, Vollard would ship tubes of paints in lieu of money. Visiting Gauguin at his barn-like studio, Vollard saw three Van Goghs over the artist’s bed – and went on to mount the first retrospective exhibition of Vincent Van Gogh, containing such masterpieces as The Potato Eaters, and Wheatfield with Crows. But the 19th-century public weren’t readily accepting. Vollard observed, “I was totally wrong about Van Gogh! I thought he had no future at all, and I let his paintings go for practically nothing.”

Once he was financially secure, Vollard was able to devote time to fostering younger artists. In 1901, at the age of 19, Picasso visited Vollard with a selection of the 100 paintings he already had to his name, with an eye to exhibit. Ahead of its time taste-wise, the show wasn’t a hit. Six years later, Vollard stood speechless in front of Picasso’s groundbreaking Cubist work Demoiselles d’Avignon. Les Nabis, young ‘prophets’ of art, comprising Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard and Felix Vallotton, depended on Vollard for their livelihood. Vollard latched on to other members of the artistic avant-garde, including Fauvists Braque, Matisse, Rouault and Vlaminck. Vollard represented the vanguard of Paris artists: it took a genius to pick a genius.

Vollard by Picasso 1910

Opinions about Vollard differed widely. Some, like Henri Matisse, complained that the dealer exploited them, equating his name with the French word for thief, voleur. Vollard said of Matisse “M. Matisse is a very dangerous man because he has an excellent memory”.

Others valued his loyalty and generosity. Cézanne was forever grateful to Vollard for rescuing him from obscurity. Renoir was a lifelong friend, although on occasion he had to kick the nosy Vollard out of his studio.

Pissarro thought Vollard was a moth drawn to the flame of artistic genius, but the unflappable dealer wasn’t one to burn out.

Buying low and selling high, Vollard could hold on to the artists’ works for years. His artists urged him to speed up a little. An obstinate man, Vollard had unerring taste and knew when the time was ripe for selling. His sloth-like strategies became his modus operandi. Picasso was impressed with Vollard’s sales technique. Vollard thwarted buyers with his pointless delays. His tactic was to pretend to nap in his chair so he could listen to his customers without being obviously interested. The psychology of the sale was more important than emphasis on price, yet if he felt he was being talked down, he would successfully talk the price back up.

Described as a gruff and boorish fellow, writer and collector Gertrude Stein similarly described him as a “huge, dark man”. Subject to abrupt shifts in mood, Vollard was an amusing storyteller but often lapsed into morose silence. He was also patient and gentle, endearing qualities captured by Bonnard’s 1924 painting, Ambroise Vollard with his Cat.

Portrait of Ambroise Vollard with his cat by Pierre Bonnard

A familiar face

Picasso joked that Vollard had his portrait painted more than any beautiful woman. Indeed, Bonnard, Cézanne, Renoir and Rouault all captured his likeness. “I think they all did him through a sense of competition,” Picasso said. “Each one wanted to do him better than the others.” In 1910, Picasso himself painted a multi-faceted portrait of him, bragging, of course, that it was the best, but left the public to ask what it meant.

Renoir painted Vollard as toreador in 1917, stealing Picasso’s Español thunder out from under him. “All I ask of you is that you do not fall asleep,” Renoir implored. Many artists gave him the same warning. Cézanne wished Vollard could be as inert as one of his apples.

Artistic licence abounds in Vollard’s 1936 memoir, Recollections of a Picture Dealer, but it provides a look into the lives of the artists just as the artists’ biographies reveal Vollard’s. No romantic entanglements are included in his biography: Vollard’s family were his artist friends. The cellar of his gallery became the Cave de Vollard, where he treated the usual subjects to his speciality of chicken curry Réunionnaise. Other people soon begged to be included. The fame of his dinners even spread to the foreign press. The imposing Rodin appeared in this speakeasy-like setting. The doyenne of French arts, Misia Natanson, also elbowed her way in. Renoir brought with him a woman disguised as a nun. For 30 years, Vollard’s famous cellar was a hub of artistic life in Paris.

Anonymous photo of Ambrose Vollard, mid-left with diners in his famous cellar,

In 1918, a rival picture dealer crowed, “Vollard, the wealthiest dealer in modern pictures. He is a millionaire ten times over!”. Known for their priceless collections, included amongst Vollard’s customers were self-made millionaire chemist Albert C. Barnes, whose collection was the pride of Philadelphia, and Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo. In fact, Vollard soon became Stein’s go-to source for all things ‘Modern’. According to Vollard, nothing was more lively than Gertrude’s conversations and, he noted, her eyes sparkled with intelligence.

Some art critics thought the Great War would put an end to Cubism, but it seemed to have the opposite effect. Paintings were commodified, like wine or scrap iron, and the trade in art was brisk. Collectors became more ardent, and Vollard bought canvases in bulk from unknown artists. By the time of his death, his mansion in rue de Martignac was stuffed to the rafters with an invaluable assortment of art. But Vollard never made a full inventory – or declared an heir.

Portrait of Vollard by Cezanne, 1899 at the Petit Palais

A strange contender showed up in the form of Erich Slomovic, a young art buff who had corresponded with Vollard throughout his teens. In 1935, Vollard offered the then 20-year-old Yugoslav a job and inexplicably gave him over 500 paintings. Vollard died in July 1939 aged 73 when his limousine crashed en route to Paris from his home in Le Tremblay-sur-Mauldre. Fellow dealer Martin Fabiani was the executor of Vollard’s estate and tried to divide the collection between Vollard’s brother, Lucien, and Madeleine de Galéa, a family friend.

A bitter ending

However, with the Nazis moving on France, Fabiani quickly removed the bulk of Vollard’s inventory. The National Gallery of Canada safeguarded some intercepted paintings, but other works suffered a different fate. Slomovic deposited some 141 canvases into a Paris bank vault and returned with the rest to his native Yugoslavia.

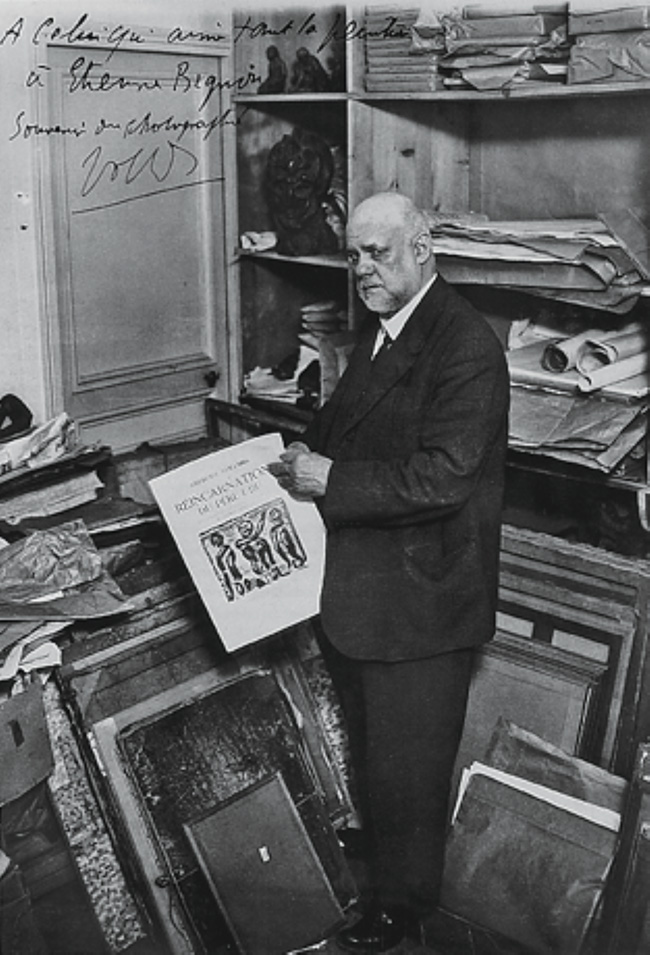

Musee d’Orsay – Therese Bonney’s 1932 photo of Vollard on rue Martignac.

He died during the Holocaust, killed at the Cuprija detention camp, and the works ended up in the Belgrade National Museum where their ownership is disputed. When the crates languishing at the Paris bank were finally wrenched open in 1979, no fewer than 15 litigants came forward, eager to claim the haul of paintings by Renoir, Degas, Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse and Picasso. A three-decade-long legal tug-of-war was eventually settled in 2006 in favour of Vollard’s descendants. Unfitting for the friend and promoter of history’s finest artists, Ambroise Vollard’s legacy met an inauspicious end.

From France Today Magazine

Lead photo credit : Ambroise Vollard photographed by Brassaï, ALL IMAGES © ESTATE BRASSAÏ-RMN; WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Ambroise Vollard, Art Collector, Art Dealer, History of Art, Parisian Art Scene

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *