In the Footsteps of Montaigne

One of the most important Renaissance philosophers and the inventor of the essay, Michel de Montaigne was also a keen traveller

In 1571, the French nobleman Michel de Montaigne sold his seat at the Bordeaux Parliament, retired from public service, sequestered himself in the circular tower of his family castle, and began to write the Essais.

Known today as one of the most influential authors of the French Renaissance, Montaigne initiated a new genre of writing, the essai, from the French verb essayer, meaning trial or attempt. Concentrating on his own thoughts and experiences, Montaigne’s Essais covered a wide range of subjects, including vanity, virtue, idleness, marriage, babies, the custom of wearing clothes, his dietary preferences, his kidney stones, the art of conversation and even cannibals. Montaigne stated: “I have embarked on a long road which I shall travel without toil and without ceasing as long as the world has ink and paper”. Without Montaigne’s influence, there would be no Pepys or Boswell, nor, perhaps, Facebook or TikTok: he was, in many ways, the first blogger.

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne was born into an upwardly mobile family whose status hung by a thread: his great-grandfather had been a wealthy herring merchant who in 1477 bought the Château de Montaigne and the title of lord that came with it. Unwittingly, the classically-educated Montaigne was thrown into a life of civic duty when his father relinquished his seat at the Bordeaux Parlement to him in 1557.

Place du Parlement in Bordeaux

Quest for knowledge

Montaigne’s motto, Que-sais je ? (What do I know?), illustrated a certain apathy that he felt towards the judicial system, but despite his cynicism, he gained entry into the French court, travelling to Paris on behalf of the Bordeaux Parlement and negotiating the welfare of the city with the royal administration. He was in regular diplomatic contact with Catherine de’ Medici and her sons, Charles IX and Henri III. With a knighthood of the Order of Saint-Michel under his belt, Montaigne could now rest on his laurels.

Withdrawing from public life at the age of 38, he moved a chair, a table and a thousand books into the tower of his family château near the Dordogne river. With the benefit of his vast collection of tomes, he spent a decade writing his essays: Montaigne could see more books spread out in his circular tower than earlier scholars had seen in a lifetime of travel; nevertheless, travel he did.

Michel de Montaigne can be imagined on horseback, riding in his satin breeches from his estate to Bordeaux, as well as elsewhere in France – Blois, Rouen, Paris, and even further afield.

Geographical details and regional idiosyncrasies greatly interested him. Travel, he said, was a very profitable enterprise, employing the soul in observing new and unknown things. Montaigne wrote that the purpose of travel was to “rub and polish our brains against the brains of others”. A naturally inquisitive ethnographer, Montaigne was keen to speak to people at all levels of society and extended his curiosity to the inhabitants of the New World, three of whom he met in 1563, when Brazilian natives were brought to Rouen by a French explorer. The suffering and humiliation imposed on these indigenous South Americans provoked his indignation and compassion.

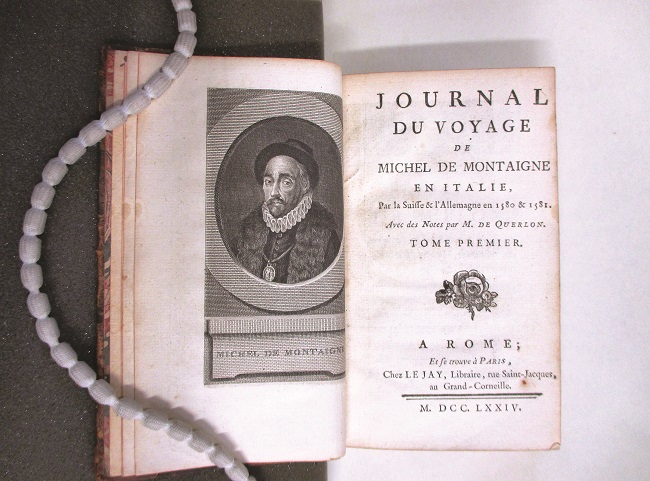

Found 178 years after his death, Montaigne’s travel journal reveals a lively description of his adventures © Bodleian Library Oxford

Montaigne’s tour of Europe

Disillusioned by constant civil and religious wars in his homeland, in June of 1580, after the publication of his first two books of Essais, Montaigne embarked on a European tour. He and his entourage travelled through France, Germany, Austria and Switzerland to arrive in Rome, a city central to his classical education. The journey was partly for pleasure and partly for health: he was plagued by kidney stones throughout his life and sought relief by taking the waters at various spas.

Despite the pain he endured, Montaigne’s cheerfulness was contagious and his attendants followed him gladly in his pursuit of unknown roads and unseen sights. In 1770, 178 years after his death, a manuscript was discovered at his château in an unexamined chest – the Journal du Voyage de Montaigne. He had spoken of his travels in his Essais, but it was thought he hadn’t kept a record of his travels. This lucky find contained a lively description of life on the road, detailing prices, food, lodgings and customs he encountered, alongside some scandalous tales.

After delivering his Essais to King Henri III, Montaigne began the French leg of his journey near Beaumont-sur-Oise. He visited Meaux, a small fortified town on the Marne which he considered very beautiful, noting its great stone walls and the riverside market which exists today in the south quarter of the old city. He also saw the Cathédrale Saint-Étienne, a beacon of Gothic architecture.

Montaigne’s path continued through the wine villages of Charly-sur Marne and Dormans. At Épernay, he visited the Église Notre-Dame and Saint-Martin’s gate, which today is all that remains of the original building. Montaigne thought the large town square at Vitry-le-François was one of the handsomest in France. The town was a crucible of gender politics where a group of young women habitually dressed as men: days before Montaigne’s visit, one such impersonator had met their end at the gallows.

Montaigne passed through the small villages of the Meuse and Vosges departments and stayed at Domrémy, the birthplace of Joan of Arc; the 15th-century building she grew up in has been restored and is now a visitor centre.

The roman baths in Plombière-les-Bains where Montaigne spent several days © Compagnie des Thermes de Plombières-les-Bains

Claiming never to travel without books, Montaigne acquired a few along the way too. He examined the well-stocked church library at Neufchâteau but found nothing rare; of greater interest, it appears, was the town’s new waterwheel.

Montaigne frequented mineral spas all the way along his route, their waters soothing the pain he suffered as a result of his kidney stones. He stopped at Plombières-les-Bains to take advantage of the thermal springs and spent his 11-day stay at the Angel Inn, the best in town where the landladies were very good cooks. The Angel is now the Residence des Bains at 7, rue Stanislas. The thermal baths bearing Montaigne’s name have been protected as a historical monument since 2001. Montaigne also visited the silver mines at Bussang, the last French-speaking village before crossing the Alsace border into Switzerland. His ultimate destination was the Vatican Library where he was delighted to see ancient Roman and Chinese manuscripts, the love letters of Henry VIII and the classics of history and philosophy. While in Italy, Montaigne was surprised with the news that he had been elected mayor of Bordeaux in absentia. The news didn’t hasten his return, however: instead he took a leisurely 45 days to return home, a journey which the courier had made in less than a month.

Montaigne returned to France via the mountainous Savoie region. Attempting Mont-Cenis was impossible for his horses, so he hired eight burly men to carry him up the mountain in a sedan chair. He travelled back down on a sleigh.

On the return trip to Bordeaux, Montaigne passed through many small, mercantile towns set among the mountains, where he enjoyed good views and good wines, collecting and polishing ideas for his third book of essays.

After spending eight days in Lyon, Montaigne stopped overnight at an assortment of villages in central France, including Thiers, which at the time was renowned for the manufacture of playing cards and carved knives. Four hundred years later, the town is still the capital of French knife-making.

Lyon © Wikimedia Commons

The Chemin de Montaigne

Established in 2015, the GR89, aka the Chemin de Montaigne, is a long-distance (326km) hiking route that faithfully follows Montaigne’s footsteps from Lyon to the village of Felletin, through the small towns he encountered on his route back home. It’s quite likely he was cooling his heels in these hamlets to delay his return to public life as Bordeaux’s mayor as long as possible.

After a journey lasting 17 months and eight days, Montaigne returned to his château on November 30, 1581. His later travels included a one-day incarceration at the Bastille, and vagabond days avoiding the plague.

He died in 1592 at the Château de Montaigne. He was 59. To this day, he remains an inspiration to get out, travel in the face of adversity, and to embrace new cultures and customs.

From France Today Magazine

Lead photo credit : Portrait of Michel de Montaigne © Wikimedia Commons

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in French culture, French history, french philosopher, walking

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY