Beauty and the Beast: The Man Behind the Myth

Chloe Govan pieces together the story of the real-life “beast”, 16th-century courtier Petrus Gonsalvus, and discovers how his cruel treatment at the hands of a diabolical queen inspired a fairy tale

The 2017 Disney blockbuster adaptation of Beauty and the Beast is officially one of the top 15 highest earning movies of all time. Yet how many of the people who have seen the film know that the original version of the story was a French fairy tale based on the life of a young man who lived in the châteaux of the Loire Valley? This story began back in the 1500s, when a human curiosity believed to be a “beast” was found on the island of Tenerife. With his entire face and body swathed in thick, dark hair, he more closely resembled a monkey than a man. Indeed, it seems that there was genuine uncertainty over whether he was a human boy or some monstrous creature.

The truth of the matter, we now know, is that this “beast” was merely a young child with the rare medical condition of congenital hypertrichosis, sometimes unkindly called “werewolf syndrome”. (And it is rare: to this day, there have been fewer than 100 cases recorded in the world.)

Perhaps acquainting him with a razor instead of mocking and ridiculing him might have helped to secure the “beast” a better future, but this was not to be. Besides, while a brief conversation with him might have revealed his inward normality, he was rarely allowed to speak. Instead, his fate was to be snatched, imprisoned in a cage and fed nothing more than raw meat and animal feed – all for the entertainment of visitors to the island.

An illustration of the Beast from a 19th-century edition of Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s version of the story. Wikimedia Commons

TWIST OF FATE

His luck changed when, eventually tiring of him, his “owners” sent him to France as a gift to mark King Henri II’s 1547 coronation. While today’s royalty and high society might blow the average annual wage on a taxidermy leopard or some extravagant jewellery, back in the 16th century it was owning a collection of living, breathing human oddities that was becoming de rigueur.

On his arrival, he was kept in a dungeon, where a succession of doctors nervously examined him, half expecting jagged claws to unsheathe themselves from his furry fingernails, or for his mouth to reveal terrifying, bloodthirsty fangs. Instead they were met by a lucid – and decidedly human – ten-year-old boy who calmly introduced himself as Pedro González. Apparently abandoned by his parents at a very young age on account of his unsightliness, he had been reduced to the status of an animal, yet had somehow retained his inherent humanity.

When Henri II was introduced to him he renamed the boy Petrus Gonsalvus (a Latinised form of his name), and installed him at one of his châteaux in the Loire Valley. The patient king saw potential in the boy that everyone else had disregarded, and set about giving him a proper formal education. The “beast” therefore became well-versed in Latin, French literature and even military techniques; and his knowledge quickly rivalled that of any local aristocrat.

Just as occurred in some versions of the future fairy tale, underneath the beast’s hairy exterior was an intelligent prince in disguise.

Portrait of Petrus Gonsalvus. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

CRUEL INTENTIONS

Unfortunately, Petrus’s royal patron was killed in a jousting contest in 1559, bringing the pair’s unusual 12-year friendship to an end. This left the defenceless “beast” in the hands of the king’s cruel and calculating wife, Catherine de’ Medici, who appeared to detest the boy as much as she had detested her husband’s mistress Diane de Poitiers. Without Henri there to protect Petrus, she taunted the boy relentlessly and subjugated him back to the status of an animal.

Catherine had been scarred by a difficult past that paved the way for a hateful personality. She had become an orphan at just one month old, and when rival factions in her home city of Florence overthrew her family, she had risked being taken into captivity, just like Petrus. There had been calls for her to be chained naked to the city walls and raped by enemy soldiers when she was still a child, as a symbol of triumph.

On relocating safely to France, she had married Henri at just 14, but, for over a decade, failed to produce an heir. That said, with fertility ‘treatments’ as bizarre as smearing cow dung over her sexual organs, perhaps her difficulty was no surprise. In that primitive context, some might have questioned who the real beasts were. Yet the Queen, who was rumoured to have killed rivals using gloves laced with poison, was bitter and resentful, and unrelentingly unkind to Petrus.

Catherine de’ Medici

Freedom, of sorts, finally came for him when Catherine turned genetic engineer. The malevolent queen set her sights on tricking a woman into an arranged marriage with Petrus and was positively giddy at the thought of the bride’s face when, on her wedding day, she clapped eyes on the groom for the first time. But it all back red when her chosen ‘victim’, a beautiful woman also by the name of Catherine, became happily married to Petrus for more than 40 years.

But the marriage was only the first part of the queen’s terrible plan. Her ultimate aim was to carry out a morally dubious genetic experiment: mating the beast to see whether his wife would produce miniature creatures or ordinary humans. Of their seven children, four were born with their father’s condition.

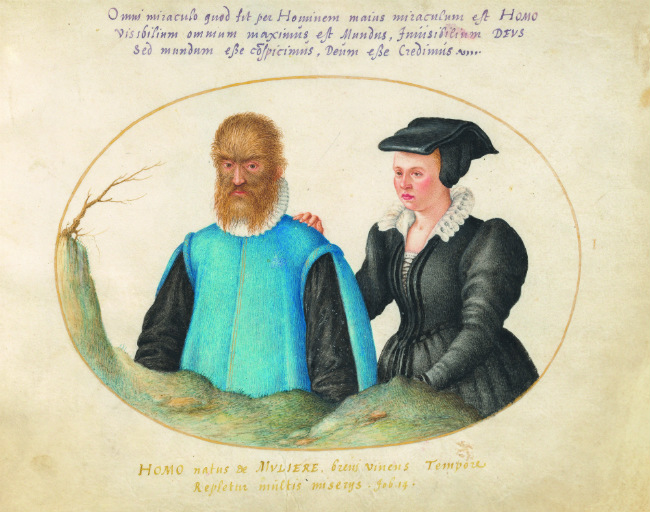

A contemporary illustration of Petrus Gonsalvus and his wife, Catherine, by Joris Hoefnagel. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

FREAK SHOW

Tragically, with Henri no longer there to defend their rights, the children were torn away from their parents to be gifted to members of the aristocracy as pets. They became famous and their portraits were painted by noblemen from around Europe.

Their “performance” tours sparked a new trend and symbolised the birth of what we would now call a freak show – something that, prior to the 16th century, had been unheard of in France.

An illustration of Beauty and the Beast’s children by Hoefnagel. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The royal courts of Europe began to delight in questionable entertainment such as staged dwarf-throwing, while also gawking at the likes of conjoined twins. Defects and physical peculiarities were all the rage, and courtiers would compete with each other to put on the most audacious shows. It was apparently the popularity of Petrus’s family that prompted the creation of France’s first permanent circus in the 1700s. He had died a century earlier, around 1618 – although, as he was considered a mere animal, the details of his demise were never formally recorded.

Beast’s daughter Madeleine. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Inspired by his portrait, in 1740 novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve dreamt up the story of a beast living in a palatial château. It tells of a man who, after illicitly picking a rose for his daughter from a garden, is threatened with death unless the daughter is brought to the Beast. The daughter, Beauty, sets off to the château willingly to save her father, and is met by an implausibly courteous creature, who – instead of raping or attacking her, as she might have expected – simply asks on a daily basis if she will be his wife.

She steadfastly refuses, though she is happy there and develops an affection for the Beast. The test of her faith comes when he allows her to visit her family, warning her that he will die of grief if she does not return within two months. Rushing back on the cusp of the deadline, she finds him dying in a cave, but nurses him back to life, and falls in love with him.

Beauty and the children from a 19th-century publication of Beaumont’s book. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The story incorporated an evil, murderous fairy – a Catherine de’ Medici character – who would stop at nothing to entrap men, even if it meant killing their families and threatening anyone who spurned her with a curse. She sentenced a royal to a life of beastly ugliness for resisting her advances, with the proviso that if he found someone to love him despite his looks, he would be restored to his former glory as a prince…

In the fairytale, the Beast comes close to death when Beauty is late returning from a visit to her father. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The fairy tale was revisited in 1756 by another French author, Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont (whose version is the most famous), and in 1946, it was made into a film by Jean Cocteau. It was even added to the school curriculum as a cautionary tale about the perils of superficiality, urging women not to shun someone based on appearances. The story also served as preparation for girls on the brink of arranged marriages, subtly asserting their obligation to remain loyal to their husbands, regardless of whether they were attracted to them.

Anyone interested in following in the Beast’s footsteps will be delighted to learn that, as well as the glories of the Loire Valley, where the story unfolded, the fictional village in Villeneuve’s original story is actually modelled on the real-life commune of Conques, Aveyron, in southern France.

Conques, Aveyron, the setting for Villeneuve’s story. Credit: Shutterstock

Meanwhile, the 2017 blockbuster starring Emma Watson based its palace on one of Henri II and Catherine de’ Medici’s residences, the breathtaking Château de Chambord in the Loire Valley. Its striking Renaissance architecture, forest surroundings (home to roving herds of red deer) and historical connection to figures such as Leonardo da Vinci make it well worth a visit – especially in the year of the artist and visionary’s death. Its park alone is as vast as inner Paris.

Travellers can also tour Catherine de’ Medici’s favourite Loire Valley palace of all, Chenonceau – which she fought over bitterly with Henri’s mistress, Diane de Poitiers.

As you wander the château’s beguiling halls and sprawling grounds, which Petrus more than likely visited all those centuries ago, spare a thought for the tragic courtier behind the fairy-tale prince.

From France Today magazine

Château de Chenonceau. Credit: Shutterstock

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *