In the Criminal-Catching Footsteps of Alphonse Bertillon

Described by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle himself as better than Sherlock Holmes, this Parisian petty clerk came to change the world of criminology. Chloe Govan explains why we should stop confusing him with a brand of ice cream…

Next time you enjoy a chilled scoop of Berthillon ice cream, spare a thought for the equally cold cases investigated by the Parisian detective who shared almost exactly the same name.

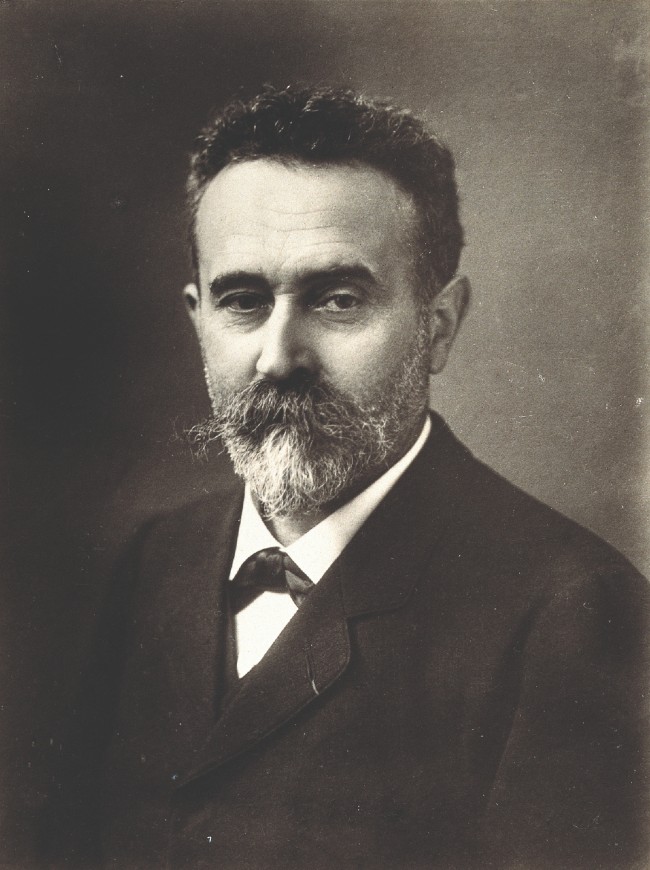

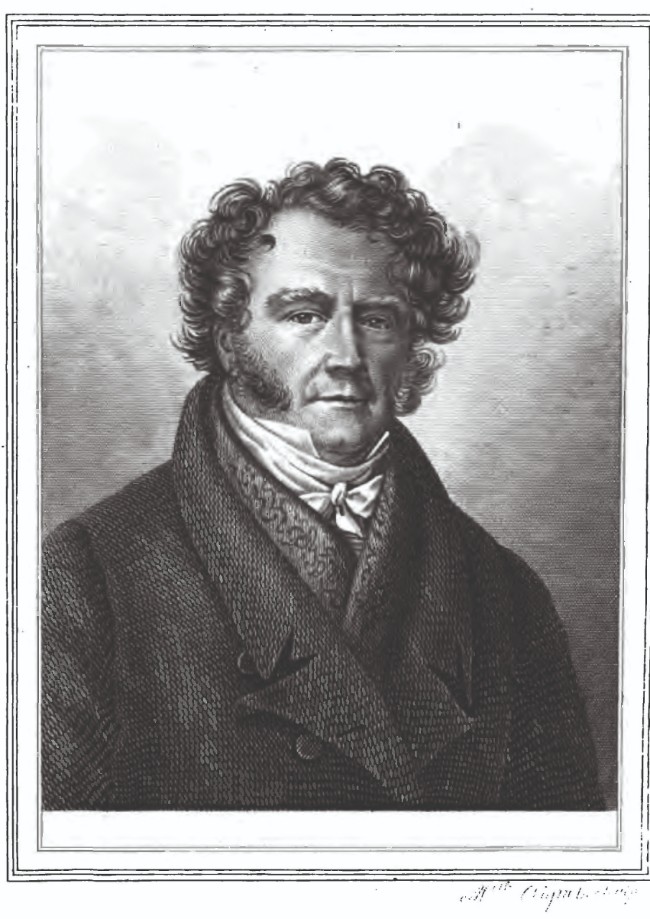

Portrait of Alphonse Bertillon. Credit: Wikimedia commons

In the late 1800s, Alphonse Bertillon came to be regarded as the founding father of forensic science. His story began in 1879 when, as a 26-year-old, he toiled at the criminal records office of Paris’s Préfecture de Police. Far from the exciting business of chasing offenders around the city, his role was to transfer a chaotic jumble of data about arrests and background checks onto individual forms – one for each suspect.

It was the 19th-century equivalent of using your computer’s copy-and-paste function over and over again, except that our hero had to do it all with pen and ink. His hand ached, his joints swelled and the repetitiveness was mind-numbing. With more than five million files and 80,000 photographs to go through, it was not just boring but seemingly interminable too.

Paris’s Préfecture de Police. Credit: Wikicommons

Why, asked a frustrated Bertillon eventually, was the classification system not a bit more sophisticated? It clearly underestimated the intelligence of shrewd criminals too. Records were filed under name, but felons would cunningly change theirs every time they were arrested, and distort their facial features in photographs to avoid subsequent detection. With so many files to pore over, the chances of successfully recognising a repeat offender, let alone ever convicting one, seemed almost non-existent.

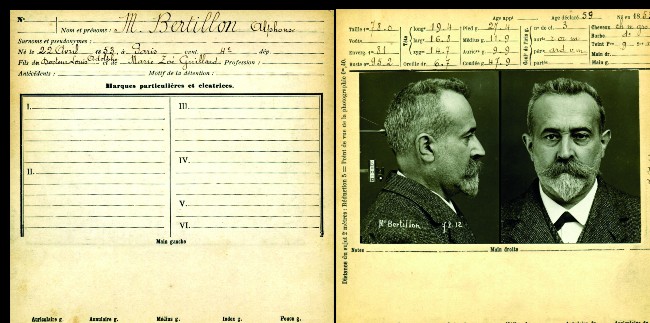

Alphonse Bertillon set the parameters by which modern mugshots are made. Photo: Alamy

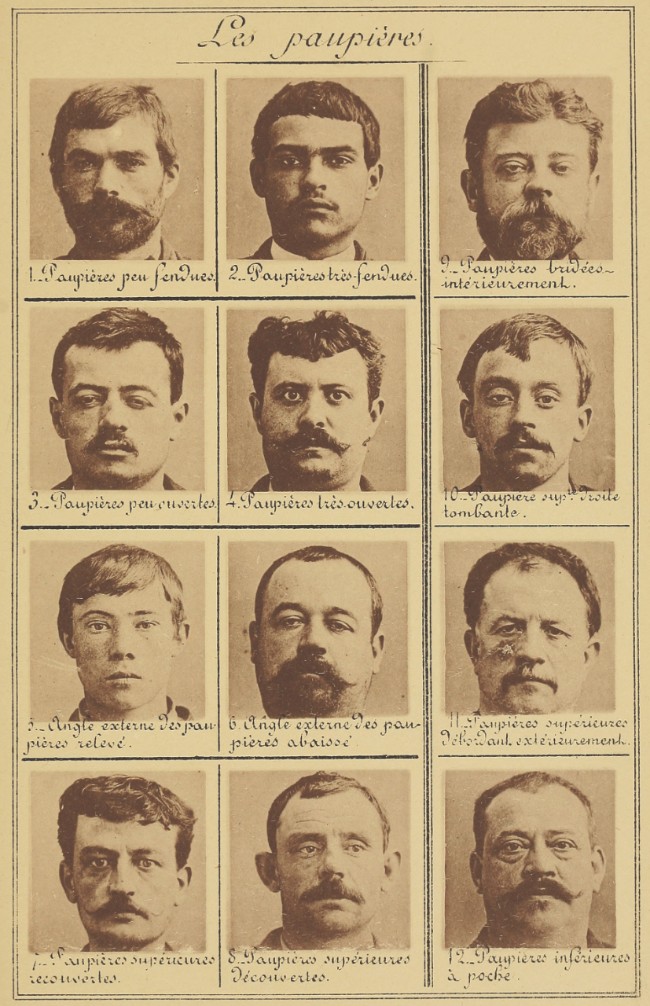

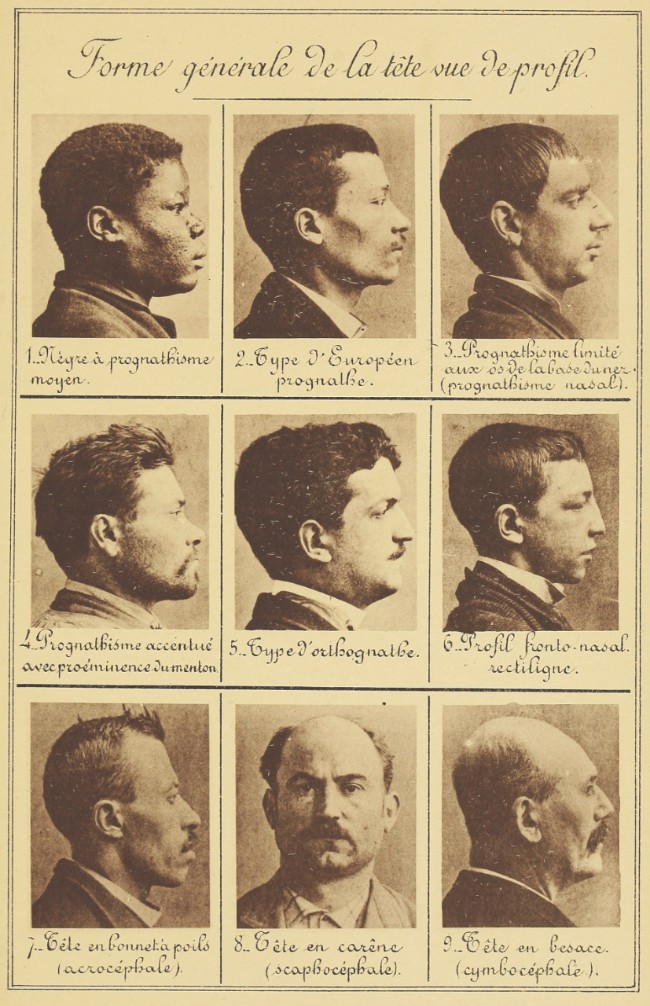

Bertillon decided that a new filing system should be devised, based on characteristics an adult criminal could neither change nor distort. He suggested that it was virtually impossible for any two people to share exactly the same proportions when it came to body measurements. So, armed with a tape measure, he collected the data he needed to test his theory from prisoners. Head circumferences, arm spans, lengths of feet and fingers were all carefully catalogued. And, Bertillon argued, if 11 unique measurements were recorded for each person, the odds of two people sharing the same would be more than four million to one.

Bertillon mugshots. Photo: Alamy

Today, of course, the accuracy of this method is widely recognised, with electronic surveillance systems able to single out a specific face, even in a crowd, and track it in real time. Back in the 19th century, however, Bertillon’s idea made him a laughing stock. Sneering that he was hardly the next Leonardo da Vinci and that the Police Department was no place for far-fetched inventions, his bosses firmly rejected his system. Bertillon persevered with an equally persuasive second report, but by now patience at the police station was wearing thin, and he was threatened with the loss of his job if he continued to tout his harebrained schemes. For now, the defeated clerical assistant was forced to give up on his invention and continue with the less sophisticated existing system, which, to add insult to injury, had been created by former fraudster-turned-crime fighter Eugène Vidocq.

Bertillon mugshots. Photo: Alamy

Once a deceitful, morally deplorable criminal mastermind – or, depending on who you asked, a glamorous gangster – Vidocq reformed to become France’s first ever private detective. In the early days of his new career he posed as a prisoner while spying for the police. Then, in 1833, after decades of drama, he opened his own Bureau de Renseignements, the first ever detective agency, and trained ex-convicts to become secret-service spies. He even took out a patent for indelible ink. However, he also made some powerful enemies along the way. He was arrested and thrown in jail multiple times on account of his perceived duplicity and corruption (yet always escaped unscathed).

Eugène Vidocq, Bertillon’s rival. Image credit: Wikicommons

His story would become a page-turner too, as he would star in novels written by the most eminent of Paris’s literary crowd. He played a leading part in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, with both reformed criminal Jean Valjean and police inspector Javert created in his likeness. Characters inspired by him also featured in works by Alexandre Dumas, Honoré de Balzac and Edgar Allan Poe, to name but a few.

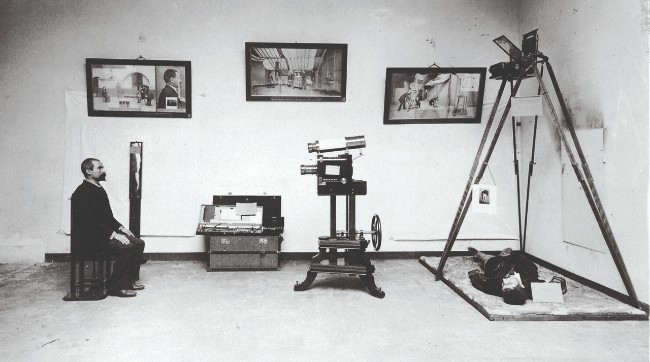

Les flics bundle off another baddie to Bertillon’s studio. Photo: Alamy

Yet when it came to identifying suspects, the methods on which Vidocq had relied had been less than scientific – for example, his claim to have a faultless photographic memory. Critical thinkers might have argued that he still had ties to the criminal underworld and chose the wrong suspects deliberately in order to save the skins of his friends. In spite of his questionable morals and wrongdoings, however, for years after his death the effects of Vidocq’s fame endured. Police inspectors simply refused to change the system he had created, leaving a frustrated Bertillon brimming with resentment – and still stuck in the same boring, dead-end job.

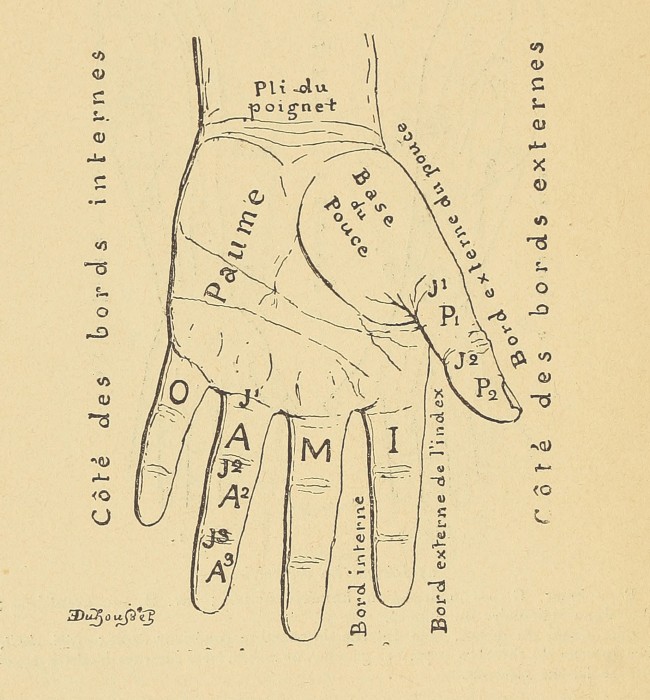

That is until 1884, when his new identification system – called ‘anthropometry’, but soon referred to as bertillonage – was finally recognised by his peers. Police forces around the world quickly adopted Bertillon’s measurements technique, while the publication of his Textbook of Anthropometry cemented his reputation as a forensic expert. The book positioned him as an authority on mugshots too, even describing his preferred lighting techniques for photographing suspects.

Diagram of hand measurements featured in Bertillon’s textbook

Bertillon also took one of the world’s first selfies, snapping his very own mugshot. This was perhaps symbolic of the celebrity status his feats in criminology had achieved, with Dresden’s police force declaring that “Paris was the Mecca of police and Bertillon their prophet”. Amusingly, he was so strongly associated with the ubiquitous police mugshot that ‘giving a smile for the Bertillon studio’ became street slang for being arrested. Even the British went to Paris for masterclasses on bertillonage, returning to London to adopt his system themselves.

And the criminal justice system has a lot more besides to thank the dogged clerk for. He was also reportedly the first to photograph latent fingerprints at murder scenes (though it was not until after his death that fingerprinting formally supplanted anthropometry as a way to identify criminals in France).

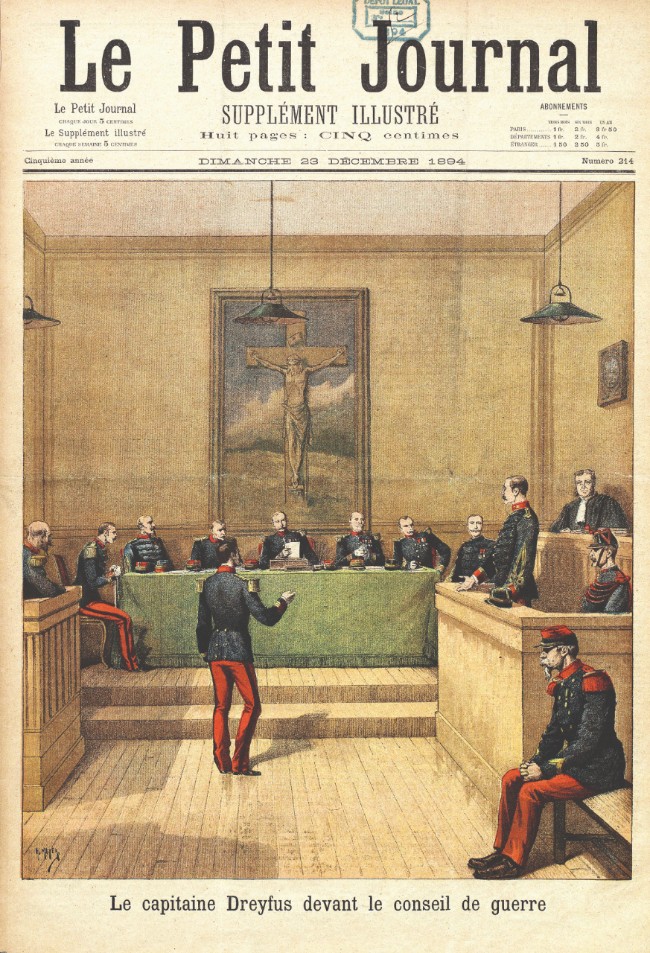

The Dreyfus Affair. Image: Alamy

UNWAVERING SELF-BELIEF

Yet Bertillon’s ego and soon unwavering self-belief was to get the better of him. In 1894, he suffered a painfully embarrassing blow. Despite having previously declared that handwriting was worthless as a method of identification as it contained “nothing unique” to an individual, he nonetheless enthusiastically accepted the challenge of analysing the scribbles of a high-profile alleged spy. Presented with a single torn and damaged note – the sole piece of evidence suggesting that Alfred Dreyfus had been selling military secrets to the Germans – Bertillon became adamant that the defendant was guilty. After briefly comparing the suspect’s known handwriting to that in the note, he confidently declared that this Jewish army captain certainly had been conspiring with the enemy.

Without a shred of concrete evidence to condemn him, Dreyfus was thus found guilty and sentenced to life in prison at the notorious Devil’s Island penal colony. It was a case that would ultimately see the world deride Bertillon as a charlatan. The Dreyfus Affair would go down as “one of the most absurd trials in the history of forensic science”.

It was the unreliable evidence he gave at the trial of Alfred Dreyfus, and his subsequent refusal to retract it, that tarnished the name of Alphonse Bertillon. Image: Public domain

Five years later, Dreyfus won the right to a retrial and British and American experts went to Paris to help clear his name, but Bertillon refused to back down – and few of his countrymen dared to challenge their very own celebrity scientist. Ironically, after the struggle he had endured to be believed when he was right, he had unquestioningly been believed when he was wrong. A year after that second trial, Dreyfus was finally pardoned and released, and a group of French mathematicians went on to highlight a “catalogue of errors” in Bertillon’s testimony. It was the beginning of the end for the forensic expert, who stood accused of “shambolic pseudoscience”. It was revealed that he had no experience of handwriting analysis at all when he’d condemned poor Dreyfus to a lifetime behind bars.

Yet right up to his dying day in 1914, Bertillon insisted he’d made no mistake. Stubborn pride, anti-Semitism or genuine belief in his flawed testimony? We will never know. That said, despite the shame of this error, he still earned his place in history. And, like Vidocq, he too became immortalised in a novel. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, Sherlock Holmes is snubbed with the claim that he is merely “the second-highest expert in Europe” on criminal matters. Who then, booms back Holmes in indignation, is the first?

“To the man of precisely scientific mind, the work of Monsieur Bertillon must always appeal strongly.”

From France Today magazine

Credit: Shutterstock

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY