A Taste of Freedom: On the Trail of Oscar Wilde in Paris

For persecuted playwright Oscar Wilde, Paris was the only place he could truly feel at home. Chloe Govan retraces the famous libertine’s footsteps in the city that embraced him

According to the British press, poet and playwright Oscar Wilde was not merely a “sane criminal”, but a vile, contemptible “sexual pervert of an utterly diseased mind”. His crime? An illicit relationship with another man. Just as it had once been socially acceptable to brand some women who lived on the margins of society “witches” and execute them, homosexuality too was a punishable offence, right up until the 1960s. After a trial that left him bankrupt, Wilde was sentenced to two years of hard labour in prison at the command of the Marquess of Queensbury, the father of his lover, Lord Douglas. He was released in 1897, but – with the Marquess threatening to shoot him dead if he ever rekindled a romance with his son – it was perhaps little surprise that he immediately headed for France.

As soon as he set foot on French soil, Wilde was overcome by his new-found liberation. Just hours earlier, a baying crowd in England had followed him through the streets, taunting him and sniping that he deserved to be torn apart by a pack of wolves and eaten alive. At the time, frozen in fearful passivity, Wilde could have done little more than sarcastically praise their imagination. Yet, here in France, he had a new identity, enjoying blissful anonymity as the enigmatic ‘Sebastian’. As it turned out, this precaution might have been unnecessary because, as Wilde remarked to one journalist: “In Paris, one can go where one likes, and no one dreams of criticising one”.

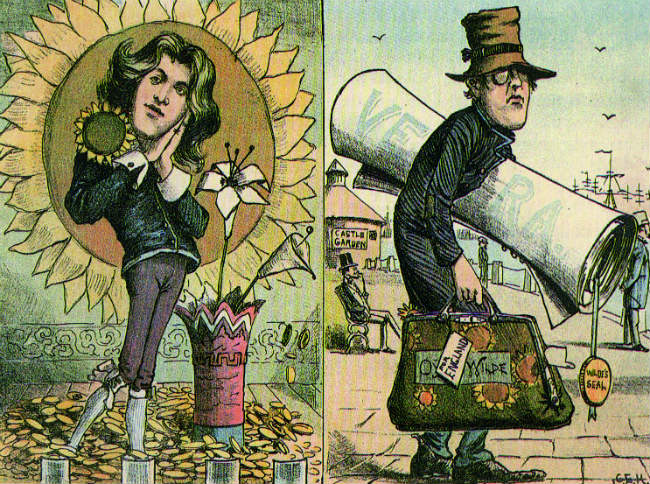

The playwright was regularly taunted by the press, as in this American satirical cartoon following the poor reception of his play Vera in the 1880s. Photo: Alamy

DANGEROUS LIAISONS

Of course, France had not always been so sympathetic – there was a time when only royalty had escaped sex scandals unscathed. Whereas King Philip I allegedly enjoyed an affair with the Bishop of Orléans in the 1100s, “common folk” with the same desires could expect to have their testicles chopped off. Repeat offenders would eventually be burnt alive and left to die an agonising death. Yet clandestine courtships continued among high society, with King Henry III of France rumoured to have preferred his male aides to his wife.

By the late 1700s, homosexuality had been decriminalised in France altogether, whereas barely 60 years ago, it was still classified as a mental disorder in the UK. In fact, gay sex was legalised in France around 150 years before women were allowed to vote. Wilde knew all too well about Paris’s progressive attitudes – in fact, prior to his prison sentence, he had enjoyed celebrity status there. When he’d first attended the Moulin Rouge back in 1891, fellow poet Stuart Merrill recalled, his ostentatious appearance had seen him mistaken for royalty: “The habitués took him for the prince of some fabulous realm of the North”.

He was even immortalised in Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings, including La Danse Mauresque. Clad in a top hat, Wilde was portrayed gazing at the fortune tellers and belly dancers on the stage – not to mention cabaret legend La Goulue. He wrote his acclaimed play Salomé in a Parisian hotel. While it was banned from the British stage due to its illicit portrayal of Biblical figures, in France it received a rapturous reception. So his sexual identity was not the first experience the outspoken author had had with prohibition in Britain but acceptance in France.

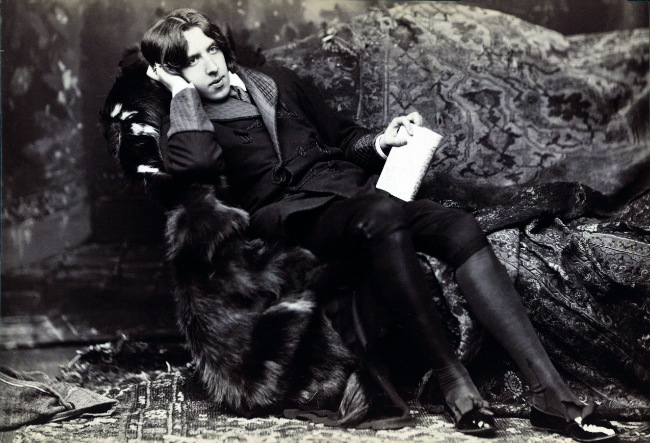

Oscar Wilde. Photo: Shutterstock

LYING IN WAIT

Although Wilde was probably in no need of privacy in Paris, he delighted in it nonetheless. Rumour had it he would mischievously wait in the aisles of his favourite bookstores and then engage in subversive conversations with anyone he spotted picking up his work. Fans would rave over the literary talent that was Oscar Wilde, little knowing that it was him they were talking to.

Other friends he made in Paris included Émile Zola and the openly homosexual André Gide. They frequented venues, havens for the alienated, where the bohemian literati could gather to enjoy Paris’s carefree, libertine spirit – such as the famous Saint-Germain-des-Prés café, Les Deux Magots. Today, as in Wilde’s day, the café’s terrace provides visitors with views of the oldest church in Paris, built over 1,000 years ago. The playwright fleetingly enjoyed Victor Hugo’s company too, joining him for baguettes as a prelude to a morning of literary debate. The bakery they visited has since been converted into the excellent Hôtel du Petit Moulin. However, during one discussion, an exhausted Hugo allegedly fell asleep!

Les Deux Magots. Photo: Chloe Govan

Wilde also indulged in his passion for absinthe in Paris. According to him, the irresistible green fairy was “satanic”, “desperately wicked” and left its users destined for “diabolism and nameless iniquity”. Yet this rarely deterred him. On drives around the Bois de Boulogne with his former lover Lord Douglas, he would often bellow with excitement, “Stop the car!” whenever they passed a decadent-looking café that served the forbidden fée verte. Incidentally, just under a decade later, the infamous “absinthe madness” murder trials rocked Europe, leading to a 100-year ban of the stuff.

Yet by the summer of 1899, Wilde was struggling to maintain his lifestyle. Since his estranged wife’s death a year earlier, payments from her had dwindled from £3 per week to virtually nothing. Remaining funds were distributed between her sons, who had been falsely informed that their father was dead. However, Wilde’s landlord at the Hôtel Louvre Marsollier accepted no excuses. He confiscated his room key and seized his property as compensation for an unpaid bill, leaving Wilde to roam the streets penniless. He eventually found salvation at the cheaper Hôtel d’Alsace – a mere hostel in comparison, but it was somewhere to rest his head at least.

A vintage scene at Les Deux Magots in the Saint-Germain district

FEATHERED FRIEND

Today it is known as L’Hôtel, and is one of the most important pilgrimage spots for anyone following the Oscar Wilde trail. Once a dilapidated flea-pit with paper peeling from the walls, room 16 now plays host to an impressively ostentatious peacock mural. The huge panel behind the bed depicts one peacock, with gorgeously textured green and gold feathers, while the side wall features two of the birds kissing. Anyone spending the night in this room will find it a challenge to turn out the lights – not over fears of Wilde’s ghost haunting his old living quarters, but because of the breathtaking beauty of the surroundings. No aesthetic setting could better be t his extravagant personality.

Oscar Wilde’s peacock passion made real in room 16 at L’Hôtel

In his final months, Wilde had strenuously insulted the wallpaper in his room, complaining to anyone who would listen that he longed for the peacock feather décor he’d enjoyed in England. In fact, one of his most famous quotes is: “Either that wallpaper goes, or I do”.

Sadly, Wilde would depart first, but acclaimed interior designer Jacques Garcia has now fulfilled his final request and created this feathered fantasy. The hotel’s aesthetic has appealed to many celebrities since; as I arrived, Jane Birkin was just checking out.

Wilde’s portrait reminds visitors of L’Hôtel’s most famous patron. Photo: Chloe Govan

It was here that Wilde became a voracious comfort-eater and so to truly capture the essence of his experiences in 19th-century Paris, eat I must – purely for research purposes, of course! The restaurant is now Michelin-starred and justifiably so, as it offers one of the highest-quality dining experiences in the city.

While L’Hôtel is today famous for its mouth-watering crab and caviar, during his stay Wilde was sadly restricted to bread and butter for lunch and two hard-boiled eggs with a minuscule serving of cognac for dinner. The party was very much over for him.

The interior of Café de la Paix

After writing pleading letters to his friends, he was eventually treated to a dinner by Lord Douglas at the historic Café de la Paix, which overlooks the Opera House – a mere minute’s walk from the street where he had written Salomé. However, when he begged for a small allowance from the immense inheritance his ex-lover had received on his father’s death, he was met with contempt. Douglas would later rant: “He disgusts me when he begs. He’s getting fat and bloated and always demanding money, money, money. He could earn all the money he wants if he would only write, but he won’t do anything… he’s like an old prostitute!”. Café de la Paix failed to live up to its name – the meal was not a peaceful one.

Café de la Paix, where Wilde dined with a former lover

END OF THE PARTY

Today the café boasts a wine list several pages long, but Lord Douglas had been adamant that his companion drank “too much” and felt reluctant to indulge him. While the illicit elixir of absinthe had once drowned his sorrows and tamed his spirit, he could no longer partake – and some of the romantically-minded artists with whom he surrounded himself were equally destitute. Eventually he was unable to settle his bill at Hôtel d’Alsace either but, a satirical wit until the end, he would merely joke unapologetically that he was “dying beyond his means”.

Oscar Wilde photo, decorated with a peacock feather, at L’Hotel. Photo: Chloe Govan

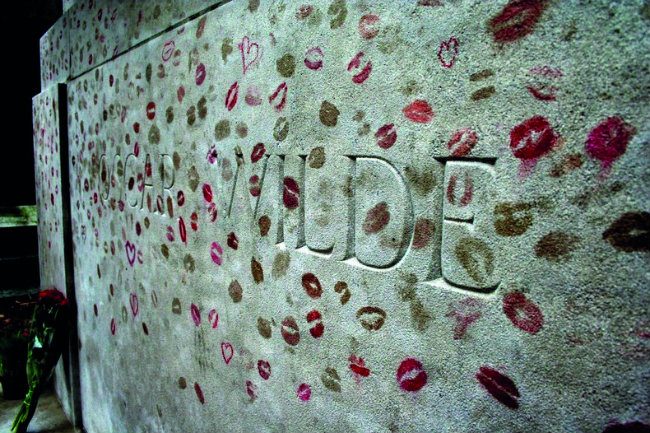

It was not merely hunger and poverty that weakened him, but a complication from an abscess he’d acquired in prison that had slowly spread from his ear to his brain. The resulting infection caused meningitis and on November 30, 1900, he quietly passed away. He was taken into the Catholic faith (which he had often jokingly insulted) and, after posthumous book sales paid his debts, was moved from a pauper’s grave to the cemetery at Père Lachaise. A then enormous sum of two thousand pounds was used to commission a giant winged sphinx, which remains on his tomb today. However, in the 1960s, in a sinister replication of France’s 12th-century punishment, the sphinx’s testicles were chopped off. Ironically, it is not merely vandalism that his tomb has had to be protected from, but love too. A barrier has now been erected to safeguard the grave from mourners’ lipstick kisses.

Lipstick kisses on Oscar Wilde’s grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery. Photo: Amusingplanet

While Lord Douglas spoke of Wilde’s “extraordinarily buoyant and happy temperament” in his final years, perhaps the most realistic – and poignant – reminder of Wilde’s true condition can be found in the last letter he ever sent to a London newspaper. “Deprived… isolated… condemned to eternal silence, robbed of all intercourse with the external world, treated like an unintelligent animal, brutalised,” he reflected of his time behind bars. “The wretched man who is confined in an English prison can hardly escape becoming insane.” These words present a vivid snapshot of the torturous memories that haunted a dying man. A man who had been denied the most basic of human rights – simply to pursue his emotions without penalty and to love whom he chose.

Beneath his “mask of mirth”, you might suspect that he had given up altogether. Though repeatedly thwarted in his quest for liberty, he had at least found a comforting taste of freedom in Paris, however fleeting. One declaration he’d made in his final years turned out to be prophetic: “Parmi les poètes de France, je trouverai de véritables amis.” (“Among the poets of France, I will find my true friends.”)

From France Today magazine

Oscar Wilde’s grave. Photo: Chloe Govan

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY