Parisian Walkways: Forgotten Montmartre

Once the haunt of supremely influential artists, Montmartre somehow manages to retain its Belle Époque allure.

On a sunny Sunday afternoon in 1876, Pierre-Auguste Renoir set up his easel at an open-air café on the top of the Butte de Montmartre – the northern hilltop overlooking Paris – and began painting. More than once, the canvas almost flew away on the wind. Yet he managed to capture the vibrant scene before him: dozens of colourfully-dressed women, men and children waltzing on a verdant dancefloor, while others, seated at benches and tables, drank and smoked pipes, chatting and flirting gaily, surrounded by trees festooned with lamps. That evening, Renoir carried his canvas back to his studio, unaware (we assume) that he had just created one of the most celebrated paintings of the 19th century: Le Bal du Moulin de la Galette.

With vivid blues, pinks, greens, and oranges, this Impressionist masterpiece is almost glowing. The sun, filtered through the trees, dapples everything with light and shadow, creating a sense of movement, of flux, and of people joyously living in the moment. And that is the source of the work’s magic: it breathes the genuine contentment of a people basking in sun and freedom after a long winter of repression. Paris had suffered in the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War; only in 1876 did peace truly return. “We rushed off into the countryside to celebrate the joy of not having to listen to any more talk about politics,” author Émile Zola wrote that year. “Paris is now thinking only of enjoying the spring sun.”

The terrace of Marcel. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Annexed to Paris only in 1860, Montmartre was still a countryside village. Perched 130 metros above smoggy Paris, here lilac and dog rose sweetened the air. There were gardens, orchards and pasture, and two windmills, whose owners hosted the popular weekly bal. This haven was soon flooded with artists. “From 1870 to 1910, Naturalists, Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Symbolists, Fauvists and Cubists, along with poets, dancers and musicians, all came together on this hill where they enjoyed a place of freedom and formidable creativity,” recounts a recent exhibition at the Musée de Montmartre (12 rue Cortot). “Rarely in history has so much diverse, unique talent appeared in such a small area, in such a short period of time.”

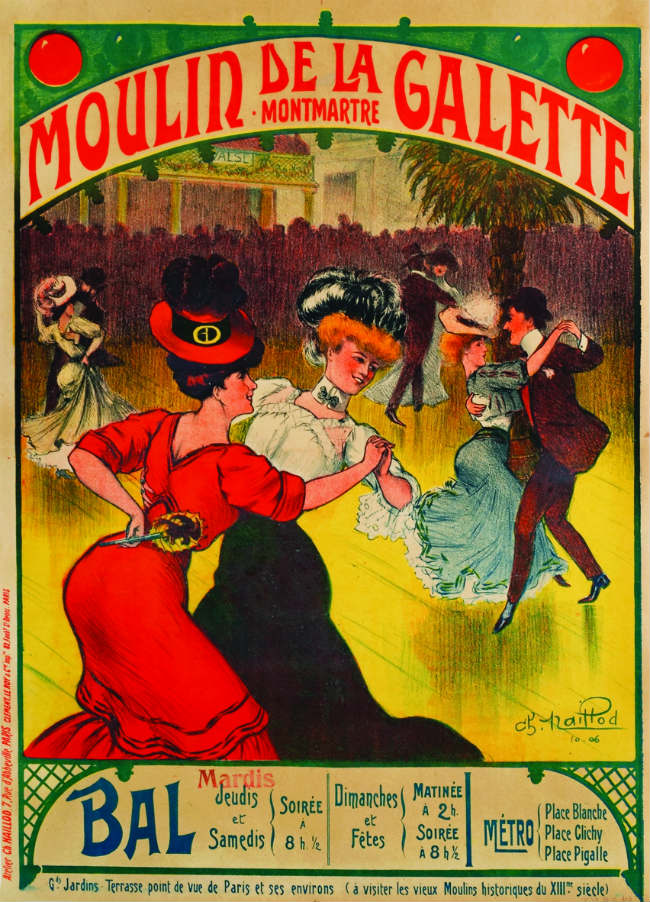

1906 cabaret

poster by Charles Naillod. ®Musée de Montmartre

Today, amidst the throngs of tourists climbing the stairs of Sacre-Coeur and squeezing onto the Place de Tertre, it sometimes seems that whatever magic once drew this talent to Montmartre is now long lost. But is it? Is it still possible to catch a whiff of that air of freedom, to stumble around a corner into a sleepy village square, a peaceful countryside garden, or a crumbling cabaret cramped with spirited artists? To walk these cobblestoned streets on a sunny Sunday afternoon, and to move sometimes just a few steps off the beaten path, is to realise that there’s a forgotten Montmartre, waiting to be rediscovered.

La Maison Rose. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Few places in Paris are as garishly urban as Place Blanche. But leave the spectacle of red lights behind, walk up Rue Lepic, past Rue des Abbesses and higher still, and soon sounds and sights we imagine ubiquitous in Paris fall away. This is what made Cédric Barbier fall in love with his hilltop neighbourhood. “When I arrive at the top of Rue Lepic, it’s like a deliverance, I don’t feel like I’m in Paris anymore,” he says. “I feel like I’m in the countryside.”

On Sundays, he walks with his wife down the quiet streets, and plays pétanque with locals at one of the neighbourhood’s tree-lined courts on Avenue Junot. Barbier’s one regret, though, since moving into his Rue Lepic apartment several years ago, was always that his street’s most iconic address had been disregarded as an underwhelming tourist trap. So when the restaurant went up for sale a couple years ago, Barbier, an engineer and entrepreneur by trade, joined with chef Nicolas Tourneville to became co-owners of historic Le Moulin de la Galette (83 rue Lepic).

The Moulin de la Galette. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Topped by one of Montmartre’s two remaining 17th-century windmills, which together mark the site where Renoir painted his tableau, Le Moulin has been reborn with a modern renovation, and the creation of a seasonal menu of made-from-scratch bistro dishes. For Barbier, offering an institution of such importance a new visage for the 21st century is a huge responsibility: “I want it to be a success, because it means I’m writing a little bit of the history of Montmartre.” The new Moulin has received rave reviews, though Barbier isn’t letting them go to his head. “I know I’m just passing through,” he says. “For now it’s in my hands, but when I’m gone, the Moulin will still be here.”

Safeguarding Montmartre’s heritage is a tradition in itself. In 1960, the historical and archaeological association Le Vieux Montmartre, founded in 1886, transformed the oldest building on the butte into the Musée de Montmartre. The 17th-century mansion on Rue Cortot was home to such artists as Renoir, Suzanne Valadon and Maurice Utrillo. In the gardens, which Renoir’s friend Georges Rivière described as a “beautiful abandoned park,” Renoir painted such masterpieces as La Balançoire (The Swing).

le Musée de Montmartre. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Today, planted with fruit trees and flowers, those gardens have been restored to their 19th-century appearance. “Our visitors are always surprised to find this oasis of calm, green and birdsong at the top of the butte,” says Jérémie Aliamus, director of the café overlooking the Jardins Renoir. But al fresco lunch possibilities and monthly nocturnes (candlelight and wine evening openings) are proving helpful in raising the profile of this under-the-radar museum.

Indeed, as precious as its collection of paintings, posters and drawings by artists like Toulouse-Lautrec, Modigliani, Kupka, and Utrillo is, this horticultural haven is a piece of living history, reminding us why these artists came to Montmartre in the first place. “The artists who came here from the mid to late 19th century were seeking freedom from the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which imposed strict rules on what they could paint and how,” says museum guide Mewen Pérez. “This new generation wanted to reflect their own world, to paint and sculpt daily life. Some used the newly expanding railway to discover the French countryside. Others didn’t go so far, and contented themselves with the countryside around Paris, particularly Montmartre.”

Today, vestiges of that bygone landscape are less rare than one might think. Just downhill from the Jardins Renoir grow gardens of quite another kind: the Jardin Sauvage Saint-Vincent (17 rue Saint-Vincent) is a ‘wild’ garden maintained by the City of Paris as a biodiversity experiment. The Musée affords a view of another exceptional sight too: a vineyard in the city. The Clos de Montmartre (Rue des Saules) represents the last 2,000 vines of a vineyard that in the 18th century spread over 42,000 hectares. It produces 1,000 bottles a year, celebrated at the Montmartre Harvest Festival in October.

La Maison Rose. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

A short walk down Rue Cortot is La Maison Rose (2 rue de l’Abreuvoir), a circa-1910 villa immortalised by the turbulent painter Maurice Utrillo and exuding a bucolic ambience that has lingered centuries. This is Rue de l’Abreuvoir (Water Trough Street) after all, of which 19th-century poet Gérard de Nerval described the nightly spectacle of horses coming home to drink, and women gathering to wash clothes and sing songs. The street leads to the narrow pedestrian walkway, Allée de Brouillards, named for its morning mists. Surrounded by lush private gardens, the walkway hasn’t lost the air which first seduced De Nerval.

Hotel Particulier Montmartre. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Soon one reaches Avenue Junot, Montmartre’s most luxurious street, with its Art Deco mansions and Villa Léandre – a stunning collection of English-style brick houses. Ironically, this splendour was built on top of the scrubland shantytown, or Maquis, where Modigliani and other penniless artists and marginal types lived until 1909. Impossible to fathom? Buzz your way through the gate at 23 avenue Junot, and the door will open onto a vast space of dense vegetation and tall trees, where you might faintly hear the clucking of chickens. The birds are the mascots of Hôtel Particulier Montmartre, a fabulously original boutique hotel, restaurant and cocktail bar, set among 900 square metres of gardens, constituting the vestiges of the forgotten Maquis. “We are not in Paris here, we are in Montmartre, protected by these two gates from the outside,” says restaurant director Paul Fargier. “It’s a hotel not entirely in the real world!”

An evening performance at the Lapin Agile. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

The same could be said of the cabaret Lapin Agile. With its iconic sign, a rabbit escaping the pot, symbolising the rebellious artistic spirit of Montmartre, it became the crossroads of poetry, art and music in Paris, where Guillaume Apollinaire, Pablo Picasso and Aristide Bruant sang and drank side by side. By 1914, the artists had followed Picasso across the Seine, and the Lapin Agile was dethroned by new Left Bank cabarets and Montparnasse cafés. Yet a century later, the nightly performances continue at Lapin Agile, where each and every evening of French chansons and cherry wine at these timeworn wooden tables is still charged with magic and emotion.

When Charles Aznavour sang La Bohème in 1965, he feared Montmartre had lost its soul. “I go for a walk, to my old address, I no longer recognise, the walls, nor the streets, which saw my youth… I look for my atelier, of which nothing remains. In its new décor, Montmartre looks sad, the lilacs are dead…” But Aznavour should take heart. Walk these streets again, you may well find that the lilacs are growing anew.

The team at the Moulin de la Galette. ® Maxime Ledieu

FAVOURITE ADDRESSES

Moulin de la Galette: 83 rue Lepic, Tel: +33 1 46 06 84 77

Renoir’s quintessential painting Bal du Moulin de la Galette captured the spirit of the 1800s, when Parisians fled the city to dance, drink and dine at this 17th-century windmill-turned-guinguette. The 21st century brought the restaurant difficult years, but new owners have transformed the landmark with a chic renovation, kind and attentive service, and bistro cuisine worth traversing Paris for!

Café Renoir- Musée de Montmartre: 12 rue Cortot, Tel: +33 1 49 25 89 39

The Musée de Montmartre had the fine idea of opening a petit café in 2014, overlooking the newly restored gardens that Renoir painted. The chance to enjoy this charming tea room, with its tables and chairs cast apparently casually about the lawns of these beautiful, historic grounds, is reason alone to visit this wonderful museum.

Café Renoir. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

La Maison Rose: 2 rue de l’Abreuvoir, Tel: +33 1 42 57 66 75

Rue l’Abreuvoir is named for a watering trough that once stood here. The trough and horses are gone, but somehow that village air lingers at La Maison Rose. Opened more than a century ago, and painted by Utrillo, La Maison resembles a country tea room more than a Paris café. That history is reflected in the prices, so rather than dine, just enjoy a drink in bucolic bliss.

Marcel: 1 villa Léandre, Tel: +33 1 46 06 04 04

Alexandra Delarive took a gamble in 2012 when she opened a chic café-bar on this somnolent street. Yet precisely because of its tranquil situation, Marcel has drawn locals and clientele from all across Paris, who come to enjoy a laid-back New York-style brunch, or a relaxing apéritif on the terrace hugging the corner of affluent Avenue Junot and picturesque Villa Léandre.

Marcel. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Hôtel Particulier Montmartre: 23 avenue Junot, Pavillon D, Tel: +33 1 53 41 81 40

This boutique hotel-mansion was an under-theradar retreat for A-list movie stars, until 2015, when the hotel opened the sublime gourmet restaurant, Le Mandragore, and lively cocktail bar Très Particulier. Today, everyone can discover this hotel with its lush gardens – one of the most transporting, verdant settings in Paris.

Au Lapin Agile: 22 rue des Saules, Tel: +33 1 46 06 85 87

This Montmartre institution was once the artistic crossroads of Paris, loved by poets and painters from Apollinaire to Picasso. A century later, an evening of French chansons and cherry wine at these timeworn wooden tables still delivers magic and emotions. For Patricia Schultz, author of 1,000 Places to See Before You Die, Lapin Agile is simply, “as authentic as the cabaret experience can be.”

Guided Tours

Jacky Libaud,“Naturalist” Tour of Montmartre & the Jardin Sauvage: www.baladesauxjardins.fr

Michel Faul, Montmartre: a village within Paris. Website

From France Today magazine

Au Lapin Agile. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Le Passe-Muraille, ‘the

Walker through Walls’ is a statue made by the actor Jean Marais as a tribute to the writer Marcel Aymé. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY